Is natural gas too expensive for its own good? [NGW Magazine]

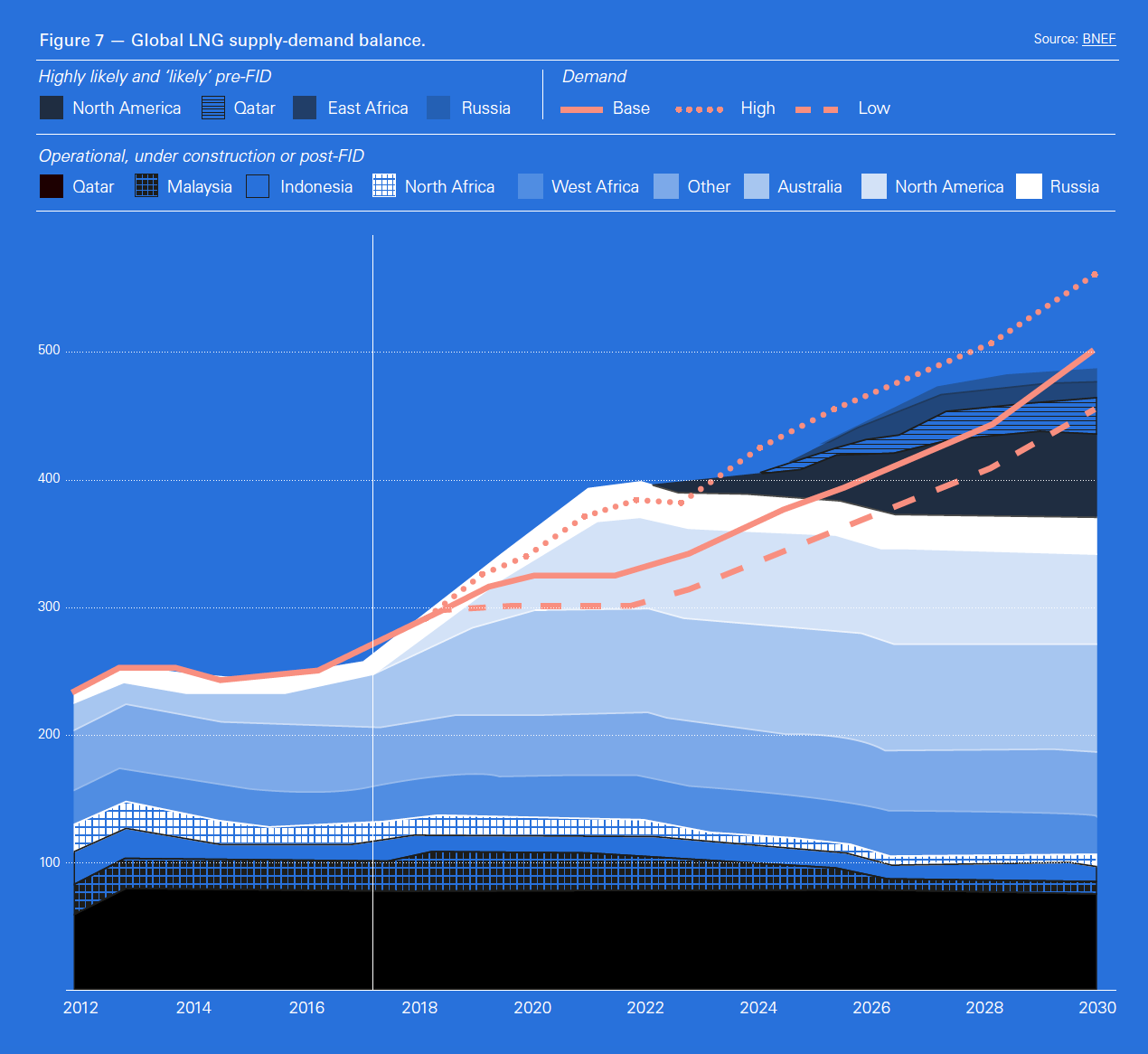

Natural gas prices in Europe, but particularly in Asia increased considerably during 2018 and are on track to reach new highs during the winter months. This upward trend started 2017 and is still continuing (Figure 1). The Platts Japan Korea Marker for cargoes to be delivered in January next year is expected to reach $13 to $14/mn Btu, in comparison with just over $11/mn Btu in January this year.

So what is the impact of such high prices on countries and consumers relying on imported LNG? What choices do they have, other than paying the price? And will they use them?

Impact on China

The double whammy of high LNG prices and the expanding trade war with the US are bringing home to China the vulnerability of having to rely on others for a significant part of its energy needs, particularly with regards to security of supplies. It is then not surprising that it is switching back to higher coal production.

The security of supply issues, which have always been of concern, came to the fore in February when central Asian gas supplied by pipelines came to the brink of collapse. CNPC was forced to launch an emergency plan after volumes on the Central Asia Gas Pipeline system fell by half due to equipment failures in Turkmenistan, and cold temperatures in Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan forced diversions of China-bound gas.

The imposition of tariffs by the US that begun in July, now fast spiraling into a wider trade war, is unnerving China. The threat of expanding tariffs to cover all Chinese imports, with the extension into economic and military sanctions are weighing heavily on the Chinese government. As is the US plan to hold sea and air naval exercises in international waters near the South China Sea and Taiwan Strait in November. And if the latest attempts by the US to stop the EU, UK and Japan from striking separate trade deals with China are met with any success, the stand-off may escalate.

The Chinese economy was already slowing and the trade war is not helping. It grew by 6.9% last year, with the momentum continuing into the first few months of this year, but now there are signs of a slowdown with weakening economic growth, partly as a result of the trade war. Economists are warning that this downward trend may last well into next year.

There are also increasing signs that this is causing China’s manufacturing sector to slow down and warnings that the trade war with the US is exacerbating this. This, in turn, could both weaken the ability of Chinese companies to pay for the higher-priced gas and reduce imported gas demand.

In terms of energy, China has retaliated by imposing a 10% tariff on US LNG in September, but not on crude oil. Even though admittedly this is less than the 25% tariff contemplated by China in August, it nevertheless makes imports of US LNG very difficult if not impossible. During 2017 China was the third largest importer of US LNG. But between June and September China had taken delivery of just four cargoes of US LNG, versus 17 during the first five months of the year.

In the meanwhile China’s coal production and demand are both rising at a rate not seen for a while. This was driven by last year’s economic growth extending into the first part of this year, which in turn accelerated electricity demand, up 9.4% during the first half of the year.

In addition, it now appears that partly as a result of the trade war with the US, China is not renewing restrictions on coal production and consumption to boost growth. Instead, it is setting limits on emissions, leaving it to regional and local governments to decide on how to achieve compliance. In addition, partly as a result of security of supply concerns and economic factors, in September China put in place restrictions on coal imports to boost domestic production. These decisions are likely to hit gas demand, especially with its price being so high. The chaotic situation that developed towards the end of last year, caused by policies that led to carrying coal-to-gas switching to its maximum, is now less likely to be repeated.

In addition, in a revised clean energy plan, released in September, aimed to ease reliance on fossil fuels and fight pollution, China’s National Development & Reform Commission (NDRC) is stepping up its renewables push with a new target to achieve 35% of electricity consumption by 2030, almost doubling the earlier target of 20%. This should cut the overall emissions caused by using more coal.

China is also building clean coal power plants and generally shifting towards cleaner coal-fired power generation by mothballing older plants and raising standards for new plants.

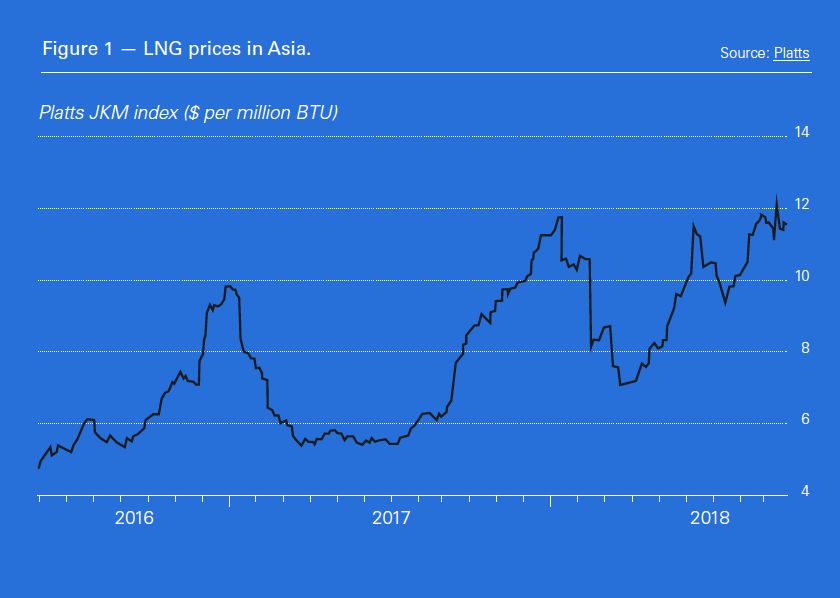

About 70% of electricity demand in 2017 was from thermal sources, with gas providing 3%, and renewables over 26% (Figure 2).

China also increased nuclear power generation in 2017 to 3.9%, up from 3.5% in 2016 and is on course to lead the world in the deployment of nuclear power by 2030. It wants 8% to 10% of its power to come from nuclear by then.

With coal-fired power generation up and new coal plants being built to that might increase China’s coal capacity by as much as a quarter, it will be interesting to see what the impact of China’s revised energy strategy will be.

Evidently the planned increase in renewables is not necessarily aimed at just reducing coal consumption. With security of supplies and energy costs being strong drivers in shaping China’s evolving energy strategy, the strongest impact may be on reducing expensive energy imports. Coal to gas switching may still remain a key longer-term driver in promoting natural gas use, driven by major city clean air policies, but it may be a more gradual process.

The security implications of the trade war with the US and sanctions, combined with increasing LNG prices, appear to have forced China to revise its energy plans.

This may also hit LNG imports, with end users seeking lower cost alternatives. Chinese LNG demand late last year and early this year may have been a key factor in the rapid rise in the price of LNG in Asia. But given the above, this cannot be expected to continue.

Impact on India

India is the fastest-growing large economy in the world, but along with other emerging economies it is facing problems. In response to these, one of the measures India is taking is import restrictions.

High oil prices are already having an adverse effect on India’s economy and the country’s currency. Since the beginning of the year the value of the rupee against the dollar went down by 15%. This is also having an adverse effect on the already high price of natural gas imports.

India imports more than half of gas in the form of LNG. This may cost up to $11/mn Btu if indexed off Brent and is vastly more expensive than domestically produced gas, now close to $3.50/mn Btu. And since the start of the year it is costing 15% more in rupees.

In the meanwhile, India’s renewables sector is expanding rapidly. Demonstrating the importance of this sector to India’s future energy needs, the government increased its renewable energy target from 175 GW to a very ambitious 227 GW by 2022. The sector is also becoming increasingly cost-competitive. The latest auction for a 1.5-GW solar photo-voltaic project at Madhya Pradesh produced the lowest-ever tariff of $0.019/kWh.

The high cost of imported LNG is affecting the cost of CNG used in transportation, city gas, electricity, petrochemicals and urea production. The latter is forcing the price of fertilisers up, with disproportionate impact on the poor of India, who rely heavily on agriculture for their subsistence.

Under the shadow of increasing LNG prices, Coal India Ltd (CIL) registered a 10.6% jump in coal production in April-September, compared with the same period last year. This is seen as important to India’s energy security and to reduce its dependence on expensive energy imports, at a time of facing economic woes. These developments strengthen coal’s dominant role in providing close to three-quarters of India’s electricity production. They also make India’s plan to raise the gas share of India’s energy mix to 15% by 2022 that much more challenging (NGW, Vol. 3/18, p.10).

Impact on Europe

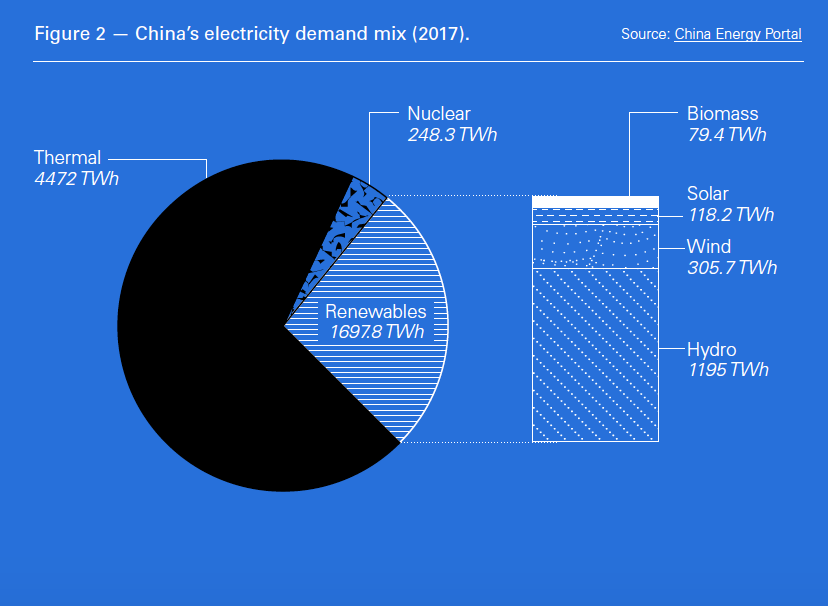

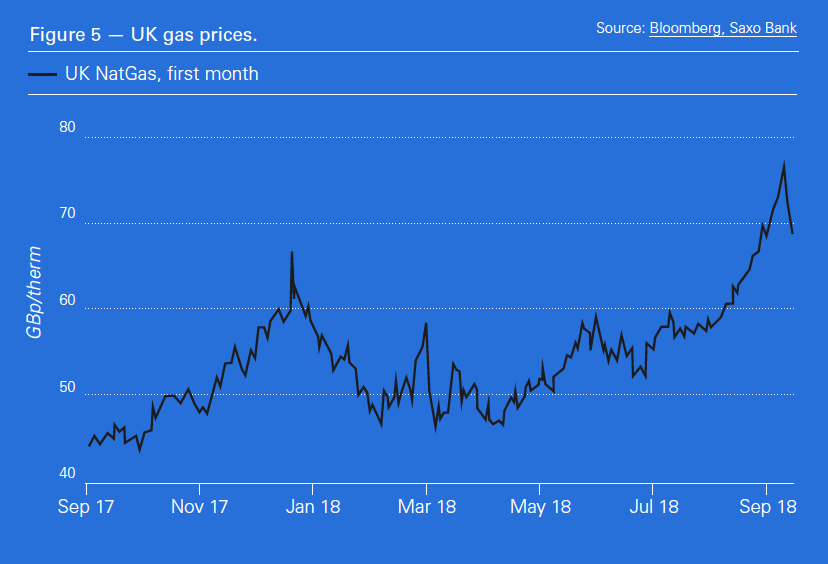

The headlines in the UK last month were that coal is making a come-back driven by high natural gas prices (Figure 3). European and UK gas prices (Figure 5) have hit three-year highs and may rise further as winter approaches. In doing so, they highlight the vulnerability of the UK becoming increasingly reliant on expensive natural gas imports.

Towards the end of August, the cost of coal that must be burnt to produce 1 MWh of electricity was about £31 (£40.7), with carbon pricing adding an extra £31 on top. In comparison, the cost of producing 1 MWh of electricity from gas was £50, with carbon pricing adding another £15, making gas more expensive and encouraging switch back to coal. The result of this is that during the first half of September UK carbon emissions went up by 15% in comparison to August. It is perhaps ironic that even in the UK price matters, at the expense of cleaner energy.

This is making UK’s ability to meet its carbon emission targets that much more challenging, with an increasing risk that these may go up for the first time in six years.

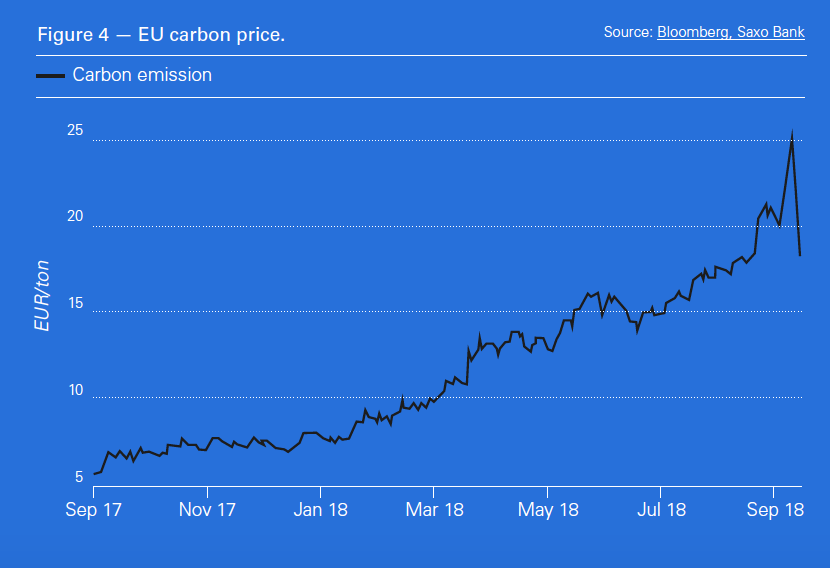

The problem is not confined to the UK alone. In addition to the higher gas prices, the rapid rise in carbon pricing is increasing pressure on gas in Europe.

The cost of carbon emissions is rising fast, driven by an EU effort to eliminate surplus carbon credit allowances. Carbon is now trading near its strongest over the last ten years, with the carbon price increasing by about a factor of four since the end of last year (Figure 4). A higher carbon price raises the cost of using fossil fuels, especially coal, which produces the most greenhouse gases, but also gas. Should this increase further, towards €30 ($34.5)/metric ton, switching to renewables, especially combined with battery storage to combat intermittency, will be strengthened even more.

As in the UK, consumers and utilities in Europe are bearing the consequences of higher carbon prices. But the idea behind these is to advance adoption of increasingly cheaper renewables, with considerable success. Higher coal and gas prices are making renewables – solar, wind and hydro – more attractive in Europe, not just in terms of clean energy but also economically.

As in the UK, consumers and utilities in Europe are bearing the consequences of higher carbon prices. But the idea behind these is to advance adoption of increasingly cheaper renewables, with considerable success. Higher coal and gas prices are making renewables – solar, wind and hydro – more attractive in Europe, not just in terms of clean energy but also economically.

But in terms of coal and gas, there is a fine balance to keep, with unexpected consequences as the price of gas goes up – over 50% higher in September than a year ago.

Oil companies expecting to benefit from higher carbon and coal prices giving an advantage to gas, must keep gas prices low and competitive – otherwise the opportunity may be lost.

Impact on the US

In the US, shale gas production is strong and it is expected to remain strong in the foreseeable future and should be able to fully cater for domestic demand as well as growing exports. This is benefiting from rising crude prices that have increased investment into oil shale prospects, resulting in greater production of associated gas at minimal additional investment.

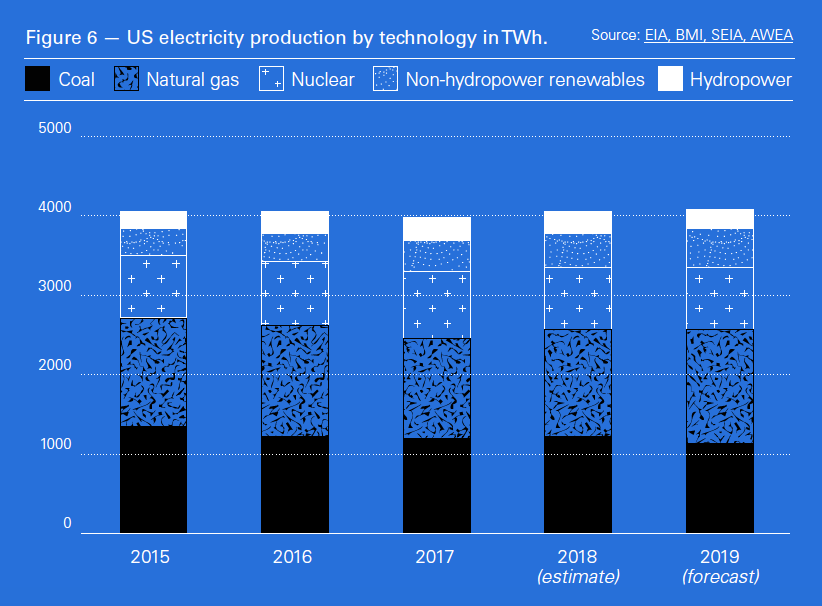

As a result, the expectation is that US Henry Hub gas prices will remain reasonably steady over the next two years, around $3/mn Btu, as gas continues to face competition from renewables combined with battery storage and coal. Despite all talk in the US about the demise of coal, it is still holding on (Figure 6).

Implications

It is clear that even though gas price setting mechanisms are driven by different factors in Asia, Europe and the US, unabated increases in oil and gas prices may soon start becoming counter-productive.

The gas industry is in danger of repeating the mistake of the coal industry last decade: overlooking the rapid advance of renewables. These are now even cheaper, and increasing oil and gas prices make the price differential even wider. With intermittency being addressed with increasing effectiveness through the use of battery storage, expensive gas faces problems, at least in terms of electricity generation. And, as shown above, coal is not going away. Price is the key factor.

As the executive director of the International Energy Agency (IEA) Fatih Birol said recently “rising oil [and gas] prices are hurting consumers and economic growth prospects today – globally but particularly in the emerging economies – but in a rapidly changing energy world could also have implications for producers tomorrow.” The rise in the oil price is also impacting LNG prices, because of oil-linked LNG supply contracts.

The impact on emerging economies is even stronger not just because of high fuel prices, but also because of their weakened currencies against a stronger dollar and exposure to dollar-denominated debt. As a result, rising prices may impact demand negatively in such countries, which also happen to be some of the fastest-growing economies in the world.

High oil and gas prices also hasten switch to renewables and back to coal. This year emerging economies are expected to overtake developed countries in terms of installed renewable capacity. China and India are now leading the development of renewable power, as they race to reduce costs and build their economies. But driven by security of supply concerns, both are also sticking to coal.

In Europe, the jump in carbon pricing is leading to increased demand for cleaner fuels. But as it goes up it is also adding to the upward pressure on gas. And in the UK it is leading to the revival of coal.

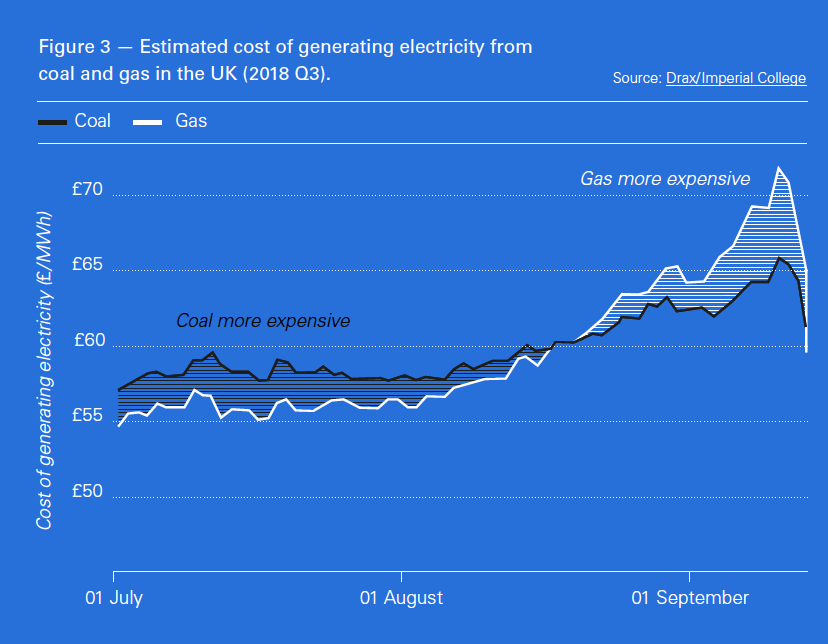

With energy demand expected to ratchet upwards during the winter months, this situation is not likely to change soon. If high prices persist they may start impacting global LNG demand.

But with substantial quantities of new LNG about to come on stream over the next four or five years (Figure 7), LNG prices may yet come down to last year’s lower levels.

LNG demand is expected to carry on growing. That’s what most forecasts show. But the impact from increasingly cheaper renewables and coal cannot be ignored. Competition will be fierce and price matters.