Why Energy Developments in Israel Matter to the EU

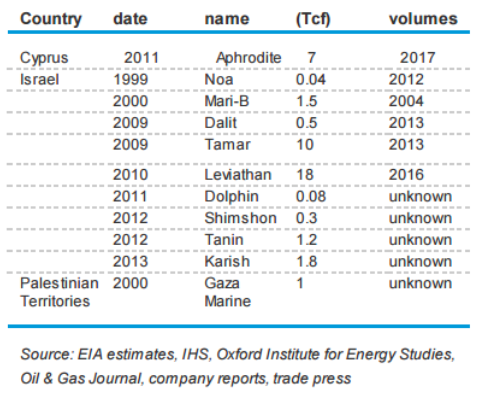

Discoveries of natural gas offshore Israel signalled the eastern Mediterranean as a new frontier for the development of natural gas resources. The gas discoveries provide a unique opportunity for Israel to change its mentality vis-à-vis neighbouring countries and view the resources as a tool for strengthening regional cooperation and solidarity through energy diplomacy. While security concerns in Israel remain paramount, diplomacy in the context of the eastern Mediterranean transcends traditional foreign and security policy considerations, and attempts to use economic and commercial means to interlink the countries of the region through energy relations.

However, the commercialisation of the gas reserves has posed significant challenges both for policy makers and the gas industry. The geopolitical complexities of the region as well as the indecisiveness of Israel’s politicians and regulators have contributed to significant delays in the production and commercialisation of the gas reserves. For example - the Leviathan field, the world’s largest gas discovery for over a decade,has been the focal point of intense deliberations. The debate’s susceptibility to political hijacking as well as the regulatory uncertainty in Israel have dissuaded potential investors, most notably Australian powerhouse Woodside. The Australian company was set to provide downstream expertise on FLNG but following long delays in agreeing a tax framework for Leviathan, Woodside returned home to a booming LNG business in Australia.

An overview of Israel’s policy on eastern Mediterranean gas reserves

In 2013, the Tzemach Committee, founded to assess government policy in the natural gas market, decided that Israel should keep 450 bcm of its reserves, allowing 500bcm to be exported by the operators of the gas fields. However, following public outcry, the government overturned the recommendation of the Tzemach Committee, deciding that Israel should keep 540bcm, and allowing the companies to export remaining quantities. The recommendation for the amount of exports was based on a demand forecast that the Israeli economy would consume 501bcm of gas by 2040, a forecast that has sunk to below 460bcm.

Since the adoption of these export quotas, the operators have committed substantial funds to further develop the resources in the region. In March 2014, after two years of negotiations, the Israeli Antitrust Authority and the Leviathan partners (Noble Energy, Delek, Avnar, Ratio Oil) agreed to terms of a Consent Decree on the ownership in the gas fields. However, in late December 2014 and ahead of the Israeli elections, the Antitrust Authority threatened to declare the operators in the region a monopoly. Antitrust Commissioner, David Gilo, envisioned breaking up the ownership of the fields and advocated for separate marketing of the gas. In response to the Israeli Antitrust Authority, further expansion of the Tamar and Leviathan fields have been put on hold.

Is there a solution in sight?

The global downturn in oil prices, combined with a precarious investment climate in Israel, fuelled speculation that international players could abandon the region altogether. However, negotiations aimed at finding a solution have been ongoing since the turn of the New Year. Following the result of the Israeli elections and the forming of a new government, politicians that had jumped on the Antitrust Commissioner’s bandwagon have softened their approach towards the operators, thus isolating the Antitrust Commissioner, who resigned from his position on 25th May. Professor Eitan Sheshinski, a newly appointed advisor to Israel’s new Minister for Energy & Water Resources, Yuval Steinitz, recently commented that there was ‘no perfect solution’ to the problem of the structure of the gas sector and that gas prices in Israel were in fact fair; the average price of gas in Israel during the first quarter of 2015 was $5.45 per energy unit.

Last week, the regulators presented their latest compromise proposal for arranging the structure of the natural gas industry to Delek Group Ltd. and Noble Energy Inc. The current plan makes no structural change in the Leviathan reservoir, and the partners will not be required to market the gas separately. Instead, the price of natural gas in future contracts will be loosely controlled, at least until competition is generated. In the Tamar reservoir, the compromise requires Delek to sell its holdings within six years, and Noble Energy to dilute its holdings from 36% to 25%. Both Delek and Noble Energy will also have to sell all their holdings in the Karish and Tanin reservoirs, as per the original arrangement.

The development of eastern Mediterranean gas reserves is reaching a critical point. Partners in Tamar and Leviathan are intent on transporting gas to Egypt. Furthermore, despite public opposition, the US State Department has been hard at work promoting a deal that would bring Israeli gas to Jordan. The realisation of these projects requires a solution to the Antitrust issue. In the absence of such a solution, the development of the gas reserves will be called into question, predominantly for two reasons: 1. There are few companies in the world with the technical know-how to undertake the deep horizon drilling that characterises the eastern Mediterranean; 2. If there are companies with the required technical expertise, they are probably present in Arab countries and do not want to risk their business relations by investing in Israel.

Where does Europe come in?

From a European perspective, the proven discoveries in the eastern Mediterranean (510bcm) may only equate to approximately a year’s worth of EU gas consumption (EU gas = 480bcm/a), but according to the US Geological Survey, the potential resources in the eastern Mediterranean could well surpass the combined production of Norway, the UK and the Netherlands – no small feat.

The Cypriot dimension of the eastern Mediterranean had shown promise for the EU but the downgrading in the size of the findings in Block 12 (aka. Aphrodite) and the poor results of exploratory drilling by the ENI/Kogas consortium and Total have made the creation of an LNG facility in Vasilikos non-viable from an economic standpoint. For Cyprus, a likely path forward includes the building of a pipeline from Block 12 onshore Cyprus to feed domestic demand (around 0,7 bcm/a) with the rest of the gas going to Turkey and from there onto international markets – pending a solution to the Cyprus problem. The more optimistic scenario would be if Israel, in cooperation with the operators, decided to pool the Leviathan and Aphrodite fields together and build an LNG facility in Cyprus. This scenario could foster the creation of the Mediterranean Gas Hub which the EU mentions in its Energy Security Strategy, presented in May 2014.

For now, the EU should focus on commercial developments between Israel and Egypt. The Egyptian government recently announced its intention to authorise the importing of natural gas from Israel to Egypt through the existing Arab-Israeli pipeline via reverse flow. Furthermore, Tamar and Leviathan partners have signed Memorandum’s of Understanding with European companies present in Egypt’s LNG facilities, Idku (Union Fenosa) and Damietta (BG Group). The deal to bring Leviathan gas to Damietta is now in the hands of Shell following the buyout of BG. Nevertheless, both the presence of a major like Shell and a Spanish company present opportunities to the EU in the short term as well as the medium to long term. In the short term, EU companies will be responsible for providing Egypt with a clean, stable and reliable energy supply. Energy disruptions and energy prices have toppled governments in the past and the EU certainly has an interest in promoting peace and stability in Egypt post Arab Springs. In the medium to long term, if gas exports to Egypt prove successful, then the chances of gas arriving to EU countries through Egyptian LNG could rise dramatically. Such a development would be in line with the EU’s policy goals for diversification and its anticipated LNG strategy - set to be presented with the European Commission’s Winter Package for Energy. The presence of Union Fenosa in particular could prove interesting to the Spanish government. Spain is host to the largest number of regasification facilities in the entire EU. Moreover, a study published by Oxford Energy Institute in December 2014 underlined that gas from Spain’s LNG facilities had the potential to replace a third of Russian gas supplies in Western Europe if a gas interconnector between Spain and France were to be established.

Using its own energy diplomacy, the EU should engage with Israel on energy matters. Israel is the largest stakeholder in the eastern Mediterranean and the EU and Israel should work together to develop the resource basin for the benefit of all, promoting regional cooperation, regional stability as well as environmental integrity.

Constantine Levoyannis is Deputy Head of the Greek Energy Forum and Athanasios Pitatzis is Member of the Greek Energy Forum. The opinions expressed in the article are personal and do not reflect the views of the entire forum or the companies that employ the authors.

Follow Greek Energy Forum on Twitter @GrEnergyForum and Constantine @clevo275 and Athanasios @thanospitatzis

Natural Gas Europe welcomes all viewpoints. Should you wish to provide an alternative perspective on the above article, please contact editor@minoils.com

Kindly note that we only lightly edit content for grammar and do not edit externally contributed content.