Kuwait to lead MENA LNG demand [Gas in Transition]

The Middle East has vast natural gas reserves and is one of the largest LNG exporting regions in the world. Yet it has still proved a source of LNG demand.

Historically, Middle Eastern hydrocarbon producers have focused on oil exports. While Qatar, Oman and the UAE all export LNG, the development of gas for export, either by regional gas pipelines or as LNG, has been slow in countries such as Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and Iran, with the latter’s gas export ambitions repeatedly delayed by international sanctions.

These three countries have used associated gas and then non-associated gas to meet domestic power demand, to support oil production through reinjection, and as an additional feedstock for petrochemicals, rather than as an export commodity in its own right. Domestic gas use has been and remains a means of freeing up oil for export.

Kuwait becomes primary LNG market

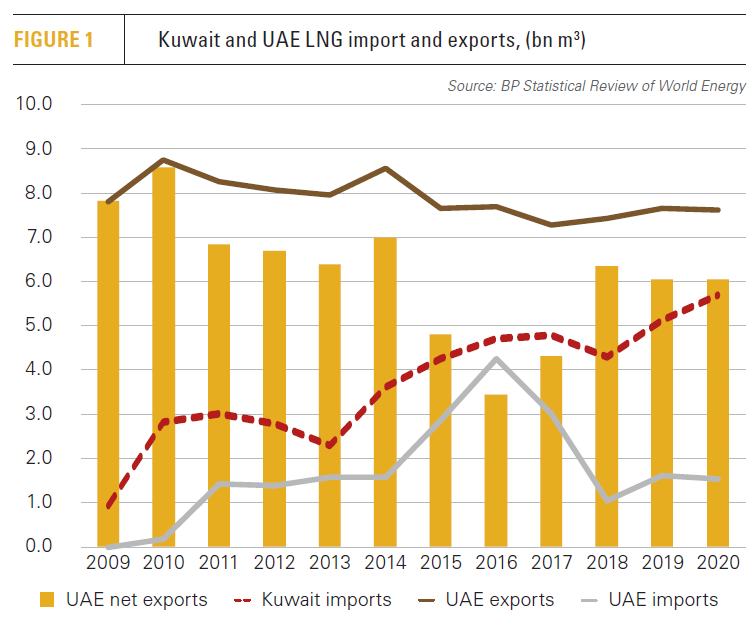

Kuwait has larger proven gas reserves than Norway, but is now the largest LNG importer in the MENA region. LNG imports have risen steadily from 0.9bn m3 in 2009 to 5.7bn m3 in 2020 (see figure 1), largely through the use of floating storage and regasification units (FSRUs). However, a milestone was passed in July with the opening of the country’s first onshore regasification terminal, Al Zour, which is designed to import up to 22mn metric tons/year of LNG.

Bloomberg New Energy Finance forecasts the Middle Eastern LNG demand will grow by 50% by 2025, from a baseline of just under 7mn mt/yr (9.4bn m3) in 2020, with Kuwait being the primary consumer.

S&P Global Platts estimates that Kuwaiti gas demand overall will rise from 20.7bn m3/yr to 35.1bn m3/yr by 2040, rising by a compound average growth rate of 2.9%, almost double that of the regional average.

Domestic production below target

The government has plans to boost domestic gas production, the main focus of which is the sour gas Jurassic Gas Project, which is being developed in three phases. The second phase saw early production facilities brought online in 2018. This contributed to a peak in gas output of 17.9bn bm3 in 2019, a level which fell to 15bn m3 in 2020 amid the coronavirus pandemic.

Phase 3 includes two new production facilities, each of which will add 1.55bn m3 of new gas supply, in addition to 50,000 b/d of condensates. The tendering process has suffered a number of delays, but the primary contracts for production facilities 4 and 5 were announced in November. They were awarded to Kuwait’s Spetco and China’s Jereh.

Engineering, procurement, construction and commissioning is expected to take just over two years, which should see the new gas come online in 2024.

However, supply growth looks unlikely to keep pace with demand. Ratings agency Fitch forecasts that Kuwaiti gas supply will increase from 18.9bn m3 in 2020 to 27.6bn m3 in 2029. The Kuwait Oil Company (KOC) has a target of 41.3bn m3 of non-associated gas production by 2040, designed to reduce the reliance on associated gas output, which is tied to oil production.

However, Fitch puts non-associated gas output in 2020 at 5.3bn m3, almost half that of KOC’s 10.3bn m3 target for the year. The agency expects domestic gas supply to rise steadily, but is sceptical that KOC will achieve its 2040 target. It cites unrealised targets, the high cost and technical difficulty of sour gas projects and a lack of international participation in the country’s oil and gas sector as reasons for expecting production to fall short of targeted output.

The heavy reliance on state finance means capital funding is closely tied to the oil price, and while oil prices are relatively high now, downswings, as in 2019, limit state capacity to fund new projects, often resulting in cutbacks to capital expenditure plans.

At the same time, domestic demand for gas is expected to rise – at 6% annually over the next decade according to Fitch – driven first and foremost by power demand, but also by higher household consumption and petrochemicals use.

As a result, demand is expected to outstrip supply, requiring higher LNG imports, as anticipated by construction of the Al Zour LNG terminal. Fitch forecasts that Kuwaiti LNG imports will rise from almost 6bn m3 in 2020 to about 13bn m3 in 2029, making it a significant national market for the fuel.

UAE

The UAE, despite being an LNG exporter and holding 5.9 trillion m3 of proved gas reserves – enough to put it in the top ten worldwide – is a net gas importer.

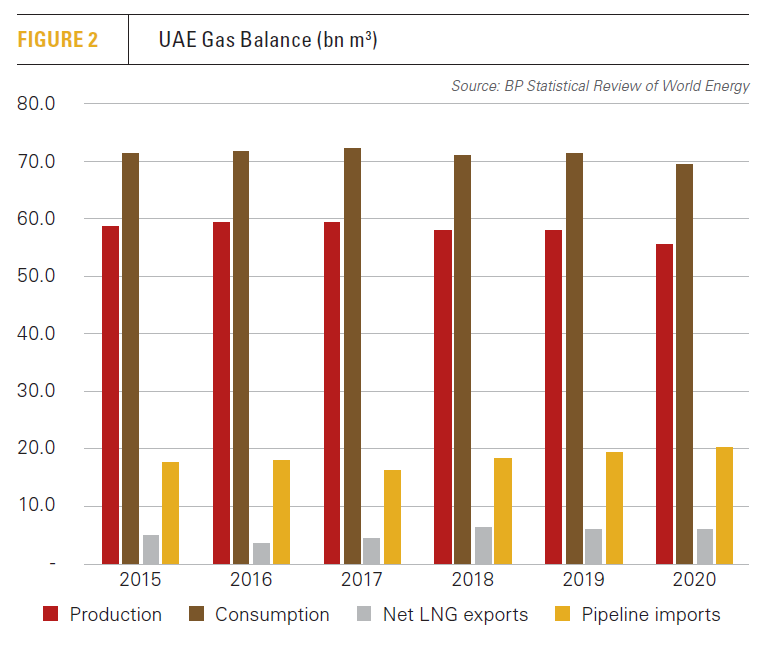

The country imports LNG and receives gas via the Dolphin pipeline from Qatar. In 2020, net LNG exports were 6.1bn m3, reflecting imports of 1.6bn m3 and gross exports of 7.6bn m3 (see figure 2). Pipeline imports totalled 20.2bn m3. The current supply agreement with Qatar runs to 2032.

Gas consumption is expected to continue rising over the next decade. S&P Global forecasts that the UAE’s gas demand will rise from 76.5bn m3 in 2020 to 85.8bn m3 in 2040.

The UAE has set a goal of gas self-sufficiency by 2030, a goal which, while ambitious, looks more realisable than Kuwait’s targets. Unlike Kuwait, the UAE is willing to partner with international oil and gas companies to increase domestic gas supply. For example, Wintershall and Eni are working with state oil and gas company ADNOC on the Ghasha ultra-sour gas development, while ADNOC and Total last year announced first gas from the Ruwais Diyab unconventional gas field.

However, of equal significance, in 2019, was the discovery of Jebel Ali, a 5,000-km2 area between the emirates of Dubai and Abu Dhabi holding shallow gas. Reserves are estimated at 2.3 trillion m3, offering the opportunity to move away from a reliance on expensive sour gas fields and access abundant gas resources.

On December 1, ADNOC reported both an increase in oil and gas reserves and a capital spending plan of $127bn over 2022-2026, up from $122bn for 2021-2025.

Renewable energy takes root

In addition to its oil and gas spending plans, the UAE has ambitions for its renewable energy sector. The country has taken a regional lead in the installation of solar power capacity, which stood at 1.9 GW at the end of 2020, achieving some of the lowest power price bids globally.

The government in December announced that the Abu Dhabi National Energy Co. (TAQA), Mubadala Investment Co. and ADNOC would partner under the Abu Dhabi Future Energy Company brand to expand renewable energy capacity. The country also has ambitious hydrogen production plans, sourced from both renewables and natural gas plus carbon capture and storage (CCS).

Boosting non-gas power generation is a central element of the strategy to reduce gas imports and meet fast growing electricity demand. The UAE will also benefit from its first nuclear reactors built at Barakah. The first unit generated power in 2020 and the third unit is expected to come online in 2023. Unit 2 is connected to the grid, but still undergoing testing.

The twin strategy of increasing domestic gas output, while limiting domestic power sector demand for gas by expanding renewable and nuclear energy, should allow the country to move towards its goal of gas self-sufficiency. This, in turn, will limit the need for LNG imports and sustain exports.

Energy hub ambitions

Domestic gas supply and inter-regional pipelines have been key determinants of LNG demand in the Middle East and North Africa’s other LNG import markets, all of which appear to have peaked, owing to the development of large Mediterranean gas finds.

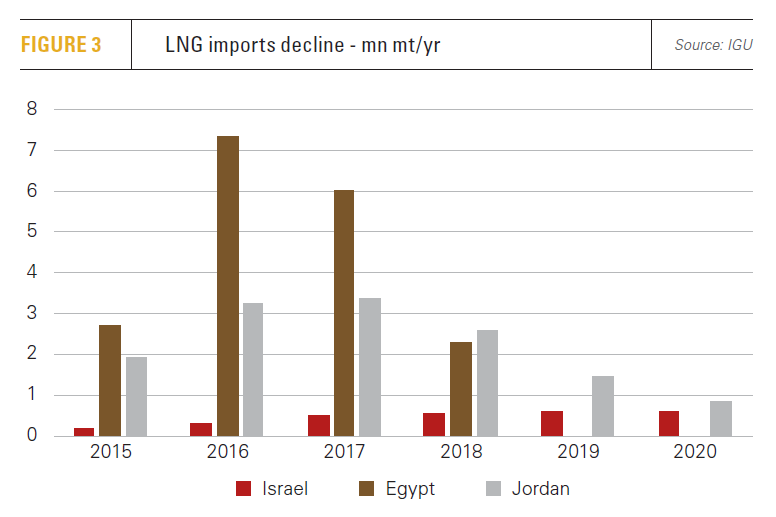

Egypt’s LNG journey has been the most dramatic, moving in rapid succession from LNG exporter to importer and back again in the space of about six years (see figure 3). Faced with domestic gas and electricity supply shortages, Egypt’s LNG imports ramped up to a peak of 7.32mn mt/yr in 2016 through the use of FSRUs, but a series of new gas developments, notably the giant Zohr field, resolved the country’s gas supply deficit by 2019 and LNG imports dropped to zero.

Israel similarly visited LNG imports as an emergency measure driven by domestic gas supply shortages both imported and domestically produced. However, these have been addressed by development principally of the Tamar and Leviathan gas fields.

Regional pipelines

Gas security in Egypt and export capacity for Israel has also been enhanced by inter-regional pipelines. Gas exports from the Leviathan field to Egypt started in January 2020 and this has aided the resumption of LNG exports from the country’s two LNG plants, both of which have now returned to operation. After a dip last year, Egyptian LNG exports rose to 4.3mn mt in the first nine months of the year, with October loadings reported to be the highest in 12 years.

Cairo has announced that it will switch domestic gas supplies away from its LNG plants to supply gas to Lebanon via the Arab Gas Pipeline (AGP). The AGP already delivers gas to Jordan and runs through Syria en route to Lebanon. While the LNG plants should still receive Israeli gas, the Egyptian move signals its prioritisation of becoming a regional gas hub.

The increase in Egyptian gas flows underlie the reduction in Jordanian LNG imports, which fell from a peak of 3.36mn mt/yr in 2017 to 0.82mn mt/yr in 2020. Jordan has also received gas imports from Israel, via the AGP, another indication of the region’s gas interconnectivity.

Gas-to-power flows

Gas and power surpluses in Egypt are feeding the government’s long-standing ambition of becoming a regional energy hub, which is also founded on expanding renewable energy and nuclear power. Egypt, in 2020, had 1.7 GW of solar power and 1.4 GW of wind with a further 500 MW of capacity combined expected to be online this year.

The country has a huge solar resource and excellent wind potential. Although progress has not been rapid, deployment is picking up, with some forecasts suggesting that solar and wind capacities close to 8 GW and 6 GW respectively are achievable by 2030.

In addition, Egypt has continued to pursue its nuclear energy ambitions and plans to construct a Russian-built 4.8 GW nuclear complex at Dabaa. The progress of the project remains uncertain, but Cairo continues to express its commitment to nuclear power and Dabaa could potentially come online in the latter half of the decade.

However, it is Egypt’s interconnector plans which add a new element to assessing future regional LNG demand. Cairo has a number of electricity interconnector projects underway, including a 3-GW line to Saudi Arabia and smaller projects expanding links with Sudan, Jordan and Iraq, as well the proposed EuroAfrica interconnector to Europe, all of which would represent a further means of exporting gas, albeit as electricity.

Al Zour LNG Terminal

The AL Zour LNG regasification terminal is the largest in the Middle East and is located about 90 km south of Kuwait City, near the border with Saudi Arabia. It is owned 100% by Kuwait Petroleum and will be operated by Greece’s DESFA.

It has a capacity of 22mn mt/yr and has eight LNG storage tanks, each with capacity of 225,000 m3, as well as two marine jetties and berthing facilities. The construction consortium was led by Hyundai Engineering and included South Korea’s state-owned KOGAS.

Kuwait last year signed a 15-year agreement with Qatar for the supply of 3mn mt/yr of LNG from 2022, which will be delivered to Al Zour.

Arab Gas Pipeline

The AGP was completed in 2010 at a cost of $1.2bn to carry gas from Egypt to Jordan, Syria and Lebanon and has been seen as a model of Arab cooperation. It is 1,200 km long, is connected to lines running subsea and overland to Israel, and was once considered a candidate for extension to the Turkish-Syrian border for onward connection into Europe’s Southern Gas Corridor.

The first section of the pipeline runs from Arish in Egypt to Aqaba in Jordan, including a 15-km subsea section under the Gulf of Aqaba. Its second part then runs to El Rehab 30 km from the Jordanian-Syrian border and the third section takes it to Jabber in Syria. The fourth segment of the Syrian part of the pipeline connects the Syrian city of Homs with Lebanon.

The petroleum and energy ministers of Egypt, Syria, Jordan and Lebanon signed on September 8 a new agreement to deliver Egyptian gas through the AGP to Lebanon.

The pipeline has suffered numerous difficulties, not least a lack of Egyptian feed gas shortly after its inauguration. The direction of gas flow was reversed from 2015-2018 to alleviate Egyptian gas shortages with imported LNG supplies from Jordan. The subsea branch line to Israel has been reversed to allow gas from Leviathan to flow to Egypt.