LNG as shipping fuel goes global [Gas in Transition]

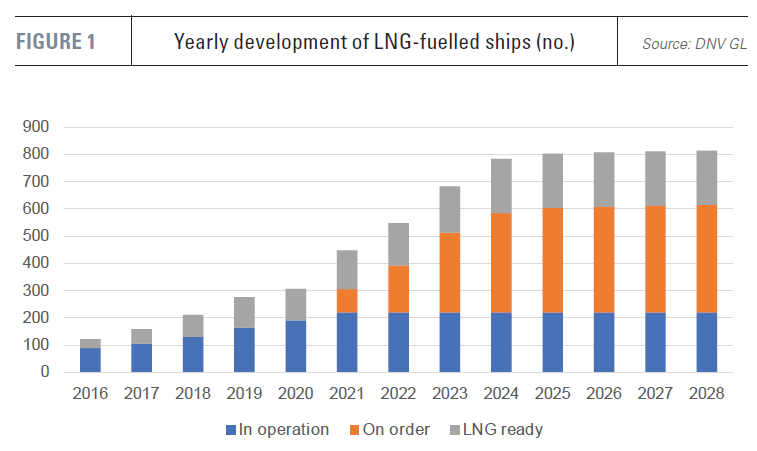

One year ago, there were just under 170 LNG-powered vessels in operation worldwide, with the new construction order book indicating growth to just over 400 by 2027 (Figure 1), not including LNG carriers.

Data from classification society DNV GL now puts the number of LNG-powered vessels in operation at 221, with the order book indicating expansion to 610 by 2028, a significant jump from last year. The majority (80%) of new orders and operating ships have chosen dual-fuel engines.

However, the number of ships does not reveal the whole picture by any means. There are now many more, large LNG-fuelled ships – containerships, crude oil tankers and bulk carriers, for example – and it is in these segments where order book growth is most substantial.

Tonnage more accurately reflects LNG demand. While the number of ships jumps by 276% out to 2028, gross tonnage is expected to grow by close to 800%.

Segment growth

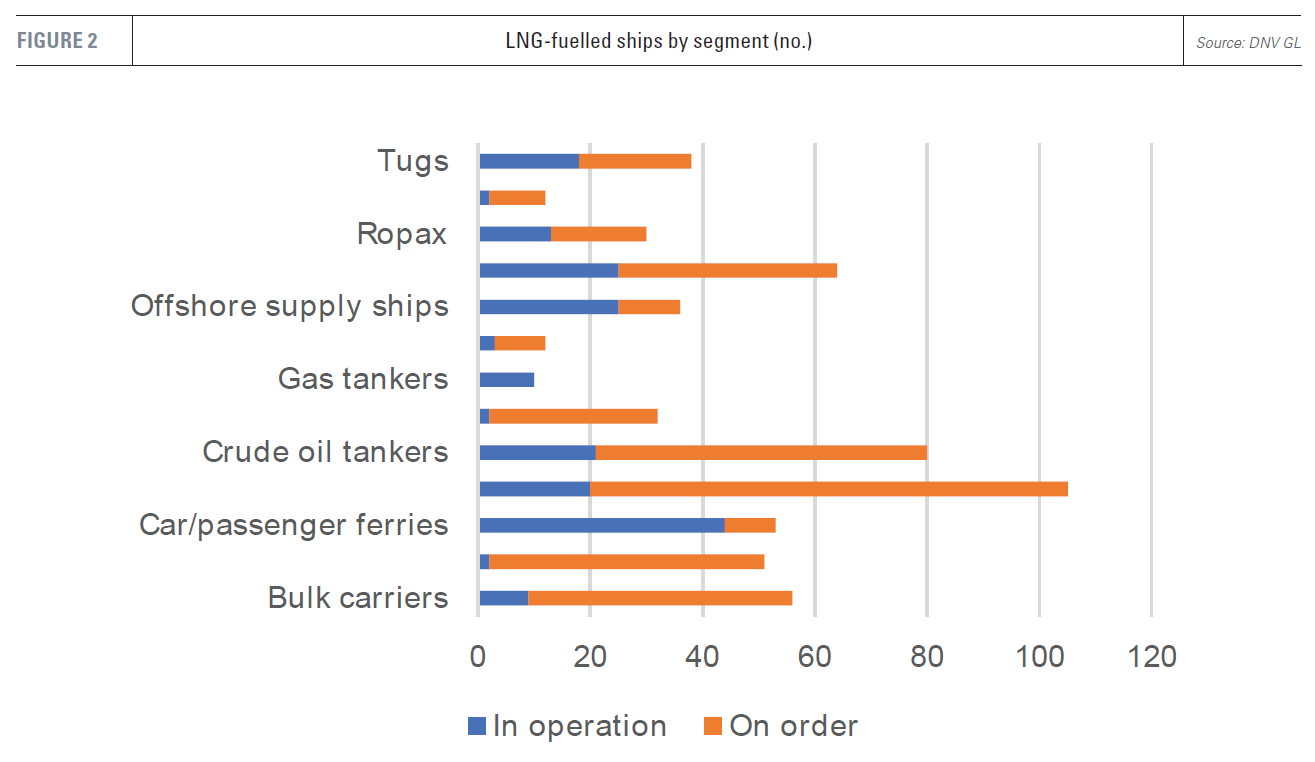

Some shipping segments (Figure 2) have seen little change in the course of the past year, notably cruise ships, the outlook for which has been particularly hard hit by the coronavirus pandemic. There has also been little growth in orders for car and passenger ferries, which by number make up a significant component of the existing LNG fleet.

This may again reflect reduced passenger journeys as a result of Covid-19, but also interest in battery-hybrid vessels and improved onshore electrical supply at European ports in particular. Hybrids replace one of a ship’s generating sets with a battery, resulting in significant fuel savings. Pure electric vessels are also growing as an option for ferries, as they have set point-to-point routes.

However, from an expected 23 bulk carriers in 2027, there are now expected to be 55 in operation by 2028, according to DNV. The number of LNG-fuelled container ships rises from 11 in 2020 to 105 in 2028, compared with a forecast for just 47 by 2027 last year.

.png) Freight rates for container ships have gone through the roof in 2021, reflecting the re-stocking of global supply chains and port congestion in almost every region of the world, leaving ship availability very low. This has prompted a rise in new orders and LNG as a fuel is grabbing its share.

Freight rates for container ships have gone through the roof in 2021, reflecting the re-stocking of global supply chains and port congestion in almost every region of the world, leaving ship availability very low. This has prompted a rise in new orders and LNG as a fuel is grabbing its share.

As newbuild rather than retrofit is generally the most economic option for LNG engines, adoption has always been hostage to the new ship building cycle, which has broadly been in a downturn in recent years with only a few segments, such as LNG carriers and offshore supply vessels, showing much dynamism. The recent jump in demand for containerships, and the rising number of ship owners opting for LNG, is therefore a good indication that LNG as a shipping fuel is proving an attractive option in a segment where new build construction has revived.

Average size increases

Crude oil carriers, bulk carriers and car carriers are also all areas of strong growth, making for a fundamental shift in the nature of the LNG-powered fleet.

Formerly dominated by smaller ships, such as ferries, tugs and offshore supply vessels, the average size of an LNG-fuelled vessel, in terms of gross tonnage, will more than double by 2028 because of growth in large ship segments.

Large ships are generally designed to travel longer distances, so the rise in their number reflects the globalisation of the market for LNG as a fuel. In 2020, DNV’s data marked just 12 ships as operating globally (Figure 3). The majority of the vessels were in Norway (35%) or in Europe not including Norway (43%).

But, by 2028, almost half of the more than 600 strong fleet are now expected to be involved in global operations.

Growth in size, number and journey length means fuel suppliers can be confident of much increased demand for LNG as a shipping fuel. In its 2021 LNG Outlook, Anglo-Dutch major Shell estimated that demand would reach 3.6mn mt as early as 2023.

|

LNG carriers demand larger than capacity adds. The largest use of LNG as a shipping fuel is from the vessels which deliver LNG around the world – LNG carriers. As these vessels carry their own fuel, they are not included in estimates of LNG demand as a shipping fuel, yet they represent a significant area of growth. They have also been an important area of research and innovation, particularly with regard to fuel tank design, boil off gas use and onboard re-liquefaction, which is carrying over into other ship segments. Consultants Rystad Energy sees LNG vessel demand rising from about 2 trillion ton-miles in 2020 to 4 trillion ton-miles in 2030. This is yearly market growth of 8%, up from 6% in the period 2015-2020, with Asia being the primary source of increased demand. Asia hosts the biggest national markets for LNG – China, Japan, South Korea and Taiwan -- which last year accounted for some 60% of global LNG demand. Rystad expects a record 64 newbuild LNG carriers to be delivered by shipyards this year, but estimates that current shipyard capacity and the new construction order book are still not yet sufficient to meet the rise in ton-mile demand. It estimates 64 new carriers will be needed annually to 2030 against existing capacity for 57 on average a year. |

Bunkering facilities

LNG-fuelled ships need bunkering facilities and steady investment in this area has encouraged more ship owners to opt for LNG as a shipping fuel.

The number of bunkering facilities has grown worldwide and LNG terminals have taken advantage of their existing infrastructure to add on marine bunkering services.

But the most popular option has been LNG bunkering vessels. These are flexible assets; many of the newer, larger ships are seagoing vessels which can serve multiple port areas, are multipurpose – for example they can be used as standard gas carriers -- and can be easily relocated.

Bunker vessels

An LNG bunkering ship is a vessel which delivers LNG to gas-fuelled ships. Average tank capacity is just over 6,000 m3, but rising.

The world’s largest operational LNG bunker vessel is the Gas Agility, which is owned by Japan’s Mitsui OSK Lines (MOL) and is under charter to France’s TotalEnergies, working out of Rotterdam. The vessel has capacity of 18,600 m3, but will soon be superseded in size by two 20,000 m3 capacity bunker vessels being built for Avenir LNG.

Growth in the size of bunker vessels reflects growth in the size of the ships needing refuelling.

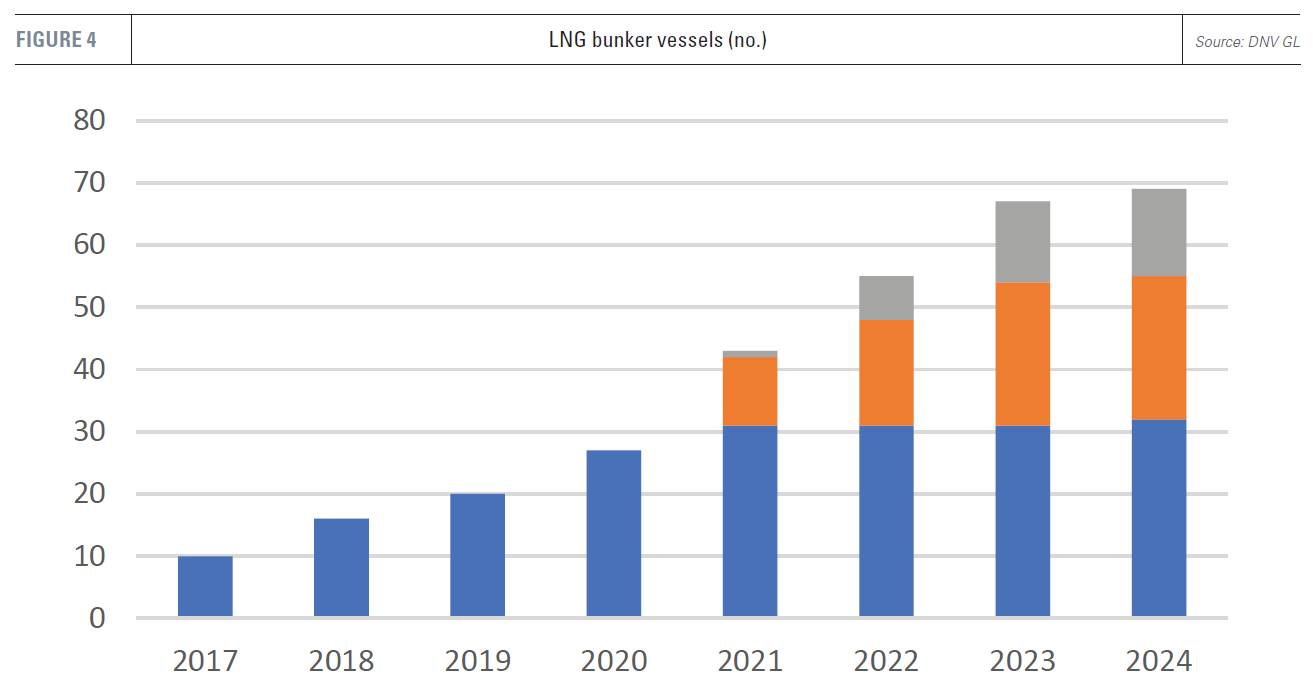

According to DNV, there were 31 LNG bunkering vessels in operation in 2021 (Figure 4), up from 16 in 2018. There are a further 23 on order for delivery through to 2024 and an additional 14 under discussion.

A bunker vessel carries three key pieces of equipment:

- a cargo containment system, which provides high performance insulation;

- a boil-off gas handling system to manage LNG vapours through cooling and re-liquefaction; and

- an LNG transfer system to deliver the LNG and deal with vapour return (cooling and re-liquefaction).

They run on boil-off gas and, depending on size, may have thrusters for positioning and/or dynamic positioning.

Ship-to-ship (STS) transfers have a number of advantages over truck-to-ship and terminal-to-ship transfers. Operations do not interfere with cargo/passenger handling, reducing port turnaround time. Bunkering can take place whether the receiving vessel is moored, at anchor or at station, providing operational flexibility. Flow rates are significantly higher than for truck-to-ship transfers.

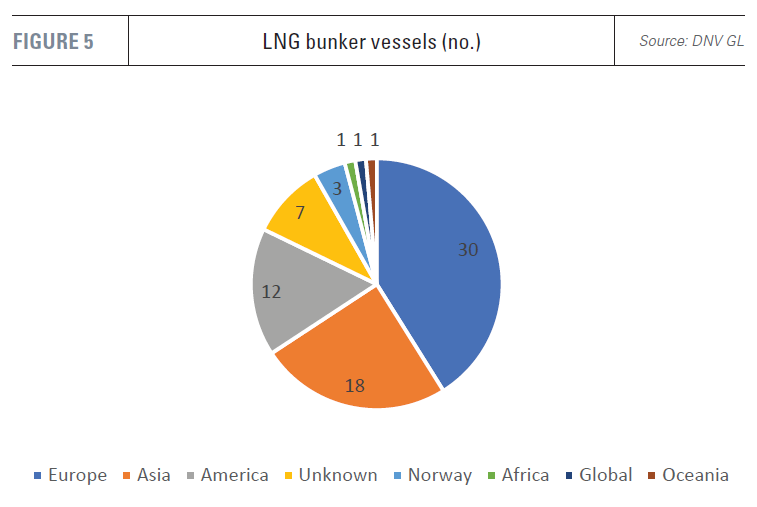

To date, most LNG bunker vessels have been deployed (Figure 5) in northwest Europe, where the bulk of the LNG-fuelled shipping fleet is located, but their international spread is clear. By 2024, DNV sees 30 in operation in Europe, 18 in Asia and 12 in America. This compares with 14 in Europe, five in Asia and five in America currently. Of particular note has been their deployment in the Mediterranean, providing LNG bunkering for long haul traffic using the Suez Canal.

To date, most LNG bunker vessels have been deployed (Figure 5) in northwest Europe, where the bulk of the LNG-fuelled shipping fleet is located, but their international spread is clear. By 2024, DNV sees 30 in operation in Europe, 18 in Asia and 12 in America. This compares with 14 in Europe, five in Asia and five in America currently. Of particular note has been their deployment in the Mediterranean, providing LNG bunkering for long haul traffic using the Suez Canal.

In its first bunkering operation carried out in November 2020, the Gas Agility delivered about 17,300m3 of LNG to the CMA CGM Jacques Saade, the world’s largest LNG-fuelled containership. The fuel supplied was sufficient for a round trip voyage between Rotterdam and Asia.

Asian ambition – Singapore aims for hub status

Singapore has been actively developing its LNG bunkering operations, aiming to leverage its position as the world’s largest bunkering port for all fuels. Earlier this year, the port authorities awarded a third LNG bunkering license to Total, allowing it to join Shell and Pavilion Energy in delivering the fuel. The agreement with Total starts from January 1, 2022 and runs for five years.

The 7,500m3 FueLNG Belina bunker vessel started operating in Singapore last year. FueLNG is a joint venture between Shell and Singaporean shipbuilder Keppel. The vessel completed its first ship-to-ship transfer of fuel to one of Shell’s crude oil tankers, Pacific Emerald, in May. FueLNG said at the time that it expected to carry out between 30 and 50 bunkering operations this year, supplying fuel to crude oil tankers, containerships, chemical tankers and bulk carriers.

Meanwhile, early mover Pavilion Energy in August said it had completed 100 truck-to-ship LNG transfers at Singapore’s Jurong Port. In 2019, the company claimed the port’s first ship-to-ship transfer, loading the fuel from the Secondary Jetty of the Singapore LNG terminal to a small-scale tanker and then on to a heavy-lift commercial vessel.

Wider Asia

In November 2019, Japan’s MOL announced it would build two LNG-fuelled ferries, which are to go into service from the end of 2022 and in the first half of 2023. The ships will replace vessels on the Osaka-Beppu route in Japan. A month later, MOL and NYK announced the construction of the first large LNG-powered coal carrier for Kyushu Electric Power Co. to be fuelled from an onshore facility.

Japan has already carried out truck-to-ship LNG transfers from a number of ports and the CLMF-operated Kaguya bunker vessel has been operating in the Chubu region since 2020. The vessel has capacity of 3,500m3. It is expected to be joined this year by a second seagoing 2,500m3 bunker vessel, which will operate out of Yokohama for Ecobunker Shipping.

The Japanese archipelago is made up of almost 7,000 islands extending over 3,000 kilometres. Owing to its lack of domestic natural gas, the country is the largest use of LNG worldwide, although it is expected to be overtaken by China this year. The country has 30 LNG import terminals reflecting its island geography, creating an ideal network for the spread of LNG use in shipping.

Other bunker vessels in Asia are a small inland LNG bunker barge in China, which has been in service since 2014, a more recently deployed 7,500m3 bunker ship at Busan in South Korea and the 7,500m3 Avenir Advantage in Malaysia. The 7500m3 SM Jeju LNG1 bunker vessel also operates in South Korea.

However, in the next three years, at least another nine bunker vessels are expected to enter service in Asia. Significantly four large bunker ships are destined for China, bringing the giant LNG consumer into the market for LNG in shipping. These will include bunker vessels with capacity of 7,500m3, 8,500m3 and two of 20,000m3 respectively. China has plans to introduce LNG for inland ship trade as well as seaborne journeys.

Singapore is expected to gain two more bunker vessels with capacities of 12,000m3 and 18,000m3, while South Korea is scheduled to receive one 7,500m3 vessel and a small 500m3 barge.

Full supply chain operations

Decisions by both Shell and Total to site bunkering operations in Singapore are likely to prove key developments in the city state’s emergence as Asia’s primary LNG refuelling hub. Total has agreements to supply CGA CGM’s fleet of LNG-fuelled containerships, which ply Europe-Asian routes, and the company will also charter two LNG-fuelled VLCCS (Very Large Crude Carriers) from Malaysia’s AET, which are expected to be delivered in 2022.

Shell is investing heavily in LNG-fuelled crude carriers, announcing in March an agreement to charter 10 more with dual-fuel engines. The ships will be built in South Korea by DSME and chartered for seven years from AET, Advantage Tankers and International Seaways. The first of the newbuilds are expected to come into service next year. By the end of 2021, already, Shell expects to have 14 LNG-fuelled ships in service.

Both oil majors are heavily invested in upstream LNG operations and both are pivoting towards cleaner fuels and renewables. By chartering and building LNG-fuelled vessels for their trading operations they are investing in both ends of the LNG supply chain, thereby reducing risk, and will be able to leverage these investments for the supply of LNG bunkers to third parties.