LNG carriers targeted by Gulf of Guinea pirates [LNG Condensed]

As pirate attacks on LNG carriers, oil tankers and other vessels have become less common off Somalia and in the rest of the western Indian Ocean over the past decade, they have ramped up on the other side of the African continent, although the violence has attracted far less international attention, perhaps because it is not associated with a failed state.

The types of vessels targeted in the Gulf of Guinea have been somewhat different, with crude oil, oil product and LNG tankers very much at the fore. This has partly been because oil and gas carrying vessels comprise a far higher proportion of international shipping off the west coast of Africa than in the Indian Ocean. However, it also appears to be the result of links between militant activity and more general petrocrime in the Niger Delta and pirate attacks.

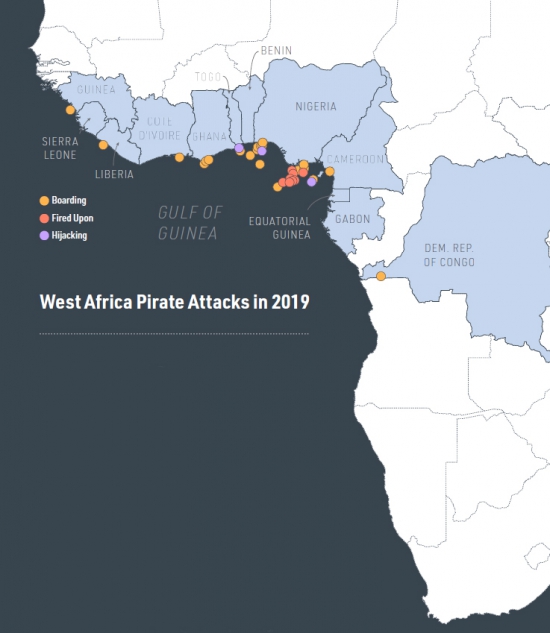

Most attacks have taken place in Nigerian waters because most pirate gangs seem to be based there and also because that is where oil and LNG tankers are sailing to and from. However, vessels have also been targeted along the rest of the West African coast, including off Benin, Togo, Ghana and Cote d’Ivoire, as well as further south, including in the international waters of Cameroon, Sao Tome and Principe and Equatorial Guinea.

Why tankers?

Pirates target tankers for two main reasons: they can hold the valuable tankers and the cargoes they contain for ransom, while holding their crews hostage; and they can rob the crews in question of money and possessions as well as removing equipment from the ship. It is easy to attack slow moving tankers with speedboats for either purpose.

Unlike with oil tankers, it does not seem possible for pirates to sell on hijacked LNG carriers or their cargoes, although there is the real threat that LNG carriers could become attractive to terrorist groups keen to make use of the explosive nature of their cargo. However, once the pirates began robbing tanker crews and holding them hostage, there was no reason why LNG carriers would not also become attractive. LNG tanker hulls are relatively safe from damage inflicted by small arms fire because of their double walled tanks.

Pirates seek to take rapid control of a carrier by boarding quickly via ladders from speedboats. The speedboats are often hosted on pirate mother ships operating in the area and the local security forces spend a great deal of time trying to identify these mother ships. Gulf of Guinea pirates are more likely to be heavily armed than those elsewhere in the world, carrying machine guns and rocket propelled grenade launchers. They also act more violently against the crews of the vessels they seize than their counterparts elsewhere.

Naval patrols within the Nigerian exclusive economic zone (EEZ) brought the situation under control and deterred attacks during 2017 and 2018. However, they have now resumed just outside the EEZ, particularly on the eastern side of it, in the maritime territory of Cameroon, Equatorial Guinea or Sao Tome and Principe.

An LNG tanker that its operator did not wish to name was attacked and shot at in November 2018. According to a report from the International Chamber of Commerce – International Maritime Bureau (IMB), “The pirates approached the vessel several times but due to the increased speed and evasive manoeuvres, the pirates were unsuccessful and later aborted the attack. Vessel and crew reported safe.”

Most recently, a speedboat with an estimated ten pirates onboard fired on BW Group’s LNG tanker Lakoja on 28 December 2019 about 65 nautical miles northwest of the island of Sao Tome, as it was on its way to the Nigeria LNG (NLNG) plant at Bonny in the Niger Delta. The vessel was able to avoid boarding and then called on international naval support which was provided when the Nigerian ship patrol Defender VI and a Portuguese naval ship, Zaire, came to its aid. Other – non-LNG – vessels were boarded during the same month and 27 crew members were kidnapped from various vessels, although the pirates were surprised by the presence of Nigerian naval personnel on board one ship.

A total of nine vessels of different types were successfully robbed or hijacked in the Gulf of Guinea last year, with 89 crew members taken hostage for ransom, so the problem seems to have well and truly returned. Moreover, the IMB fears that many pirate attacks in the region are not reported by owners who fear reprisals and increased insurance premiums, if they report a thwarted attack where no claim is necessary.

According to the IMB, in the period from January to June, the Gulf of Guinea accounted for just over 90% of maritime kidnappings worldwide. 32 crew were kidnapped in the second quarter of this year, up from 17 in the first quarter. The reported attacks happened further out to sea, two-thirds of the affected vessels being attacked around 20 to 130 nautical miles off the Gulf of Guinea coastline.

The IMB reported 98 incidents of piracy and armed robbery globally in the first half of 2020, up from 78 in the second half of 2019, although the number of ship hijackings fell to its lowest level since 1993.

Links with the Niger Delta

The links with unrest in the Niger Delta are difficult to pinpoint. There is certainly a lot of trade in stolen oil and oil products in the area, with barges and even tankers taken out to sea for distribution to willing customers within the region and further afield.

In addition, the Niger Delta is a maze of swamps and inland waterways that provide excellent hiding places for various types of petro criminals. Once an armed group is up and running, they can turn their hands to various activities, from kidnapping to onshore oil theft, extortion and piracy. Hostages taken by pirates are often held in the Delta.

Once they have speedboats and weapons, gangs can target valuable vessels and vulnerable crews. At the same time, the theft of oil from onshore and shallow water oil fields in the Niger Delta itself often requires the payment of bribes to oil industry workers, police and the naval forces sent to control them. Such connections can be usefully taken offshore, along with insider knowledge of the oil industry and ship movements.

Operating inside the Niger Delta, where Nigeria’s oil and LNG export terminals are based, makes it easy for gangs to find out when vessels are sailing. It is difficult to hide an oil or LNG tanker.

Oil gangs and general insecurity in the Niger Delta threaten the development of the LNG industry in Nigeria more widely. The seven train NLNG plant may be one of the biggest LNG liquefaction facilities in the world, but none of the roughly dozen other LNG projects planned in the country have thus far been developed. This is partly because of an uncertain investment regime, with Abuja favouring domestic gas consumption over exports, but failing to create sufficiently attractive investment regulations to enable either.

Yet militant attacks on oil and gas industry infrastructure across the Niger Delta has resulted in gas pipelines being regularly blown up, cutting supplies to gas-fired power plants and other important centres of gas consumption. The longevity of the militant activity has surely deterred potential investors from committing to the development of new LNG plants that would only justify the investment after two decades of successful commercial operation.

Counter-piracy and deterrence

Successive Nigerian governments have launched offensives to crack down on oil theft and piracy in the region. It sometimes works in some areas, but the problems re-emerge elsewhere or after a hiatus. There have also been a number of cross-border initiatives that have seen the Nigerian navy work with their counterparts in neighbouring states to track pirate vessels and hijacked tankers across international maritime boundaries.

It is difficult to get past the feeling that both types of crime could be more successfully tackled if only there was sufficient political and military will. The oil companies and tanker operators either have their own helicopters or employ security companies with helicopters that can be used to track stolen tankers, LNG carriers and pirate ships. The same can be said of the Nigerian military. In some instances, stolen tankers have been recovered by the Nigerian navy, only for them to miraculously ‘disappear’ again overnight.

There are a variety of measures that can be adopted to deter attacks on LNG tankers. Captains can sail in a defensive manner when they become aware of approaching pirates, changing direction and speeding up. Operators can also pay for security personnel to protect tankers by fighting off attacks.

Simpler deterrents are possible too, including barbed wire defences and high pressure hosepipes that crews can use to force attackers off. Many vessels have citadels, purpose built, self-contained safe areas, a little like a safe room, where the crew can hide in the event of being boarded by pirates. Military patrols can also help, although these have to be deployed in the density seen off the Somali coast to have a big impact.

Impact on insurance

Apart from the physical risk to crews and vessels, such attacks have profound implications for the insurance of LNG carriers, including on the terms offered and level of premiums. International shipping associations Bimco and Intertanko have published standard clauses that owners can insert into charter contracts, the purpose of which is to expressly address the issue of obligations, costs and responsibilities for vessels sailing through areas affected by piracy.

Those chartering vessels have to indemnify owners against all liabilities, costs and expenses arising from actual or threatened acts of piracy or any preventative measures taken, including additional insurance premiums, crew bonus costs and the costs of security personnel and equipment. Such clauses may make those chartering vessels less likely to accept such terms, but they may have no option if vessels without such stringent contracts are not available.

When LNG vessels are seized by pirates, owners generally seek support from their protection and indemnity club and underwriters, while employing negotiators to make contact with the pirates holding their vessel to secure release. Such negotiations can take weeks. The terms of ransoms paid are generally kept secret in order not to encourage copycat attacks, although the typical level of ransoms is well known to those involved, including the negotiators and the pirates themselves.

However, the attacks do not appear to have had the same impact on the cost of insuring LNG tankers as Somali piracy. Insurance costs increased by an average of 7.5% a year in the first decade of the 21st century as a result of Somali pirate attacks, according to figures from shipping consultancy Drewry, reaching $1,572/day by 2011 and resulting in the widespread use of armed guards.

Beyond the Gulf of Guinea

LNG carriers have also been attacked elsewhere in the world, including off Indonesia and Singapore. While pirate attacks in the Gulf of Guinea involve races between pirate speedboats and targeted vessels, most pirate attacks in the rest of the world are launched on vessels at anchor. For instance, last September the LNG tanker British Contributor was attacked 15 nautical miles offshore Malaysia, when three attackers boarded the ship through the anchor cable pipe and robbed it.

Concerns over potential pirate attacks on LNG carriers are growing in the Gulf of Mexico. UK security consultants Dryad Global have reported a growing problem with attacks on oil and gas industry vessels off the coast of the Mexican states of Campeche, Tabasco and Veracruz. Although it does not appear that any attacks on LNG vessels have been officially recorded, the targeted area is close to the Mexican LNG import terminal at Altamira, while the threat is also significant given the growing volume of US LNG shipments from the US Gulf Coast.