LNG on the road – the bottom line [LNG Condensed]

A number of recent studies have cast doubt on the extent of greenhouse gas emissions reductions to be gained from the adoption of LNG in transport. A report by Imperial College London’s Sustainable Gas Institute published in January suggested 16% GHG emissions savings on a full life cycle basis for road transport and 10% for shipping. An industry commissioned study unveiled in April by consultancy Thinkstep estimated well-to-wake reductions of 7-21%.

Most pessimistic of all was a study published in October 2018 by the European Federation for Transport and Environment, which concluded that “based on the latest available evidence fossil gas used in transport has no meaningful - and when including methane leakage and upstream effects in almost all cases no - climate benefits compared to petroleum based fossil fuels.” Yet this study too provided ranges showing some savings, -2% to +5% for trucks and -12% to +9% for ships compared with marine diesel rather than high sulphur fuel oil (HSFO).

|

Advertisement: The National Gas Company of Trinidad and Tobago Limited (NGC) NGC’s HSSE strategy is reflective and supportive of the organisational vision to become a leader in the global energy business. |

The key takeaways from these divergent views is that best practice LNG use will deliver greenhouse gas emissions savings in transport, but not quite to the extent that had been hoped, and not to the extent that LNG use alone will deliver the reductions necessary from transport to meet long-term climate change targets.

However, there is another aspect of LNG in transport to consider – the economics. If LNG can deliver some GHG emissions savings, improve air quality and deliver operational savings, then surely it will see rapid adoption. Studies suggest that the fuel cost savings are substantial, have existed for more than a decade, and have improved as the difference in capital cost between an LNG heavy-duty vehicle (HDV) and its diesel equivalent have fallen.

Yet LNG adoption in heavy-duty trucking has been slow. This reflects in part the lack of refuelling infrastructure, but change is in the air. The US expects to see the largest ever annual addition of new LNG refuelling stations this year. Nonetheless, LNG Condensed’s analysis suggests that the picture with regard to fuel costs savings, as with emissions savings, is more nuanced than might be expected.

Infrastructure roll out

According to reports of the Advanced Clean Transportation Expo held in Long Beach, California in May, there was no sighting of the Tesla Semi Class 8 truck. The only electric heavy truck offerings were a Class 6 truck made by China’s BYD and start-up technology integrator Thor Trucks’ ET-1, which is still undergoing road testing.

In contrast, there were a range of Class 8 trucks running on CNG and LNG, which are already in production and offered by established truck manufacturers such as Daimler, Kenworth, Peterbilt, and US Hybrid. The point is that while heavy-duty electric trucks remain largely at the conceptual stage, LNG trucks are available to drive away today, if fleet operators believe that they can offer reduced life-time costs and superior environmental performance.

For HDV’s, LNG rather than CNG is making the running. The energy density of LNG is about 60% that of diesel, as oppose to 25% for CNG. To get sufficient range between fuelling stops, LNG requires smaller tanks than CNG, albeit larger ones than for diesel. In addition, the liquid state of LNG allows faster filling with a flow similar to diesel, while high power engines require high fuel pressure injection, which is easier to achieve with LNG than CNG. As a result, LNG trucks provide the best competition to diesel in the alternative fuel market for trucks.

And it is a big market. According to the American Trucking Associations (ATA), 10.8bn metric tons of freight were moved by truck in 2017, representing 70% of total domestic freight. The US Bureau of Transportation estimates that the tonnage moved by trucks, not including goods moved by multiple transport modes, will rise to 14.2bn mt by 2045.

Refuelling infrastructure is a key constraint. There were just 72 public LNG refuelling stations in operation in the US (67) and Canada (5) in 2018. However, the US will see its largest ever expansion of public LNG refuelling stations this year with the planned addition of 33, representing an increase of 49%. This appears to mark a new stage of expansion, following the period 2014-2016, which saw the addition of 39 stations in total.

In addition to the public refuelling stations there are also 55 private stations in the US and 7 in Canada. 2016 was a major year of expansion in private stations, with 19 added. Additions fell to 3 in 2017, but rose again to 9 in 2018, according to Alternative Fuels Data Center (AFDC) figures.

Fuel costs

But it is fuel cost savings where LNG is supposed to score high.

A study based on Shenzhen in China published in the journal Advances in Mechanical Engineering estimated that it would take a median 1.74 years for an LNG container tractor purchase to breakeven against the equivalent diesel vehicle, if maximum subsidies (RMB 40,000) were received and 2.7 years without subsidies. For an engineering dump truck, the median breakeven periods were 0.49 and 0.99 years respectively, and for an engineering concrete mixer 0.36 and 1.07 years.

The 149 LNG-fuelled container tractors used in the study were bought at prices not replicable in the OECD of RMB 320,000 ($46,310) each, about 10% more than their diesel equivalents. The study was based on 2015, a time when oil prices were relatively low, starting and ending the year around $44/b Brent, rising to $65/b mid-year. The study also assumed a longer engine life and, for the container tractor only, lower average maintenance cost for the LNG vehicle over its diesel rival.

This contrasts with a European study published in February 2019 in the journal energies. Again, lower fuel costs are the key benefit, maximised by the intensity of vehicle use. The study estimated the fuel cost of the LNG truck at $0.306/km, $0.138/km lower than the diesel cost. Based on a new LNG truck price of $222,520, 40% higher than that of the diesel equivalent, the payback time of the additional investment was put at 4 years and 2.5 months.

In a second example, assuming a 35% higher capital cost for the LNG truck and 20% higher annual maintenance costs, the breakeven period was 2.16 years. This used a retail price for diesel at €1.15/l ($4.86 per US gallon) in first-quarter 2017 and an LNG retail price of 0.84/kg, three times the average wholesale price of LNG in Spain. The high level of European tax on diesel increases the savings.

In the US, a Department of Energy study using funds provided via the 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act found in favour of LNG-fuelled vehicles as far back as 2012, at which time the capital cost of an LNG truck, bought and used by Enviro Express to haul incinerator waste to landfill was $205,000, $90,000 or 78% higher than the diesel equivalent.

Based on mileage of just over 100,000 miles a year, the spark-ignition LNG trucks, using 95% LNG and 5% diesel, had an average fuel economy of 5.3 miles per diesel-gallon equivalent (DGE), compared with 5.5 for the diesel trucks they replaced. However, the low cost of LNG meant huge fuel savings. With LNG at $0.36/mile and diesel at $0.69/mile, the investment breakeven point was just less than three years. At the time of the study – January 2011 to March 2012 – oil prices were averaging over $100/barrel.

Price tracker

Back in 2011-2013, with oil prices at super high levels, market analysts were forecasting adoption rates of 20% for natural gas engines by 2020. In February 2017, Frost & Sullivan suggested natural gas-fuelled heavy-duty trucks would see market penetration of 7.2% in 2025, but even that is open to question.

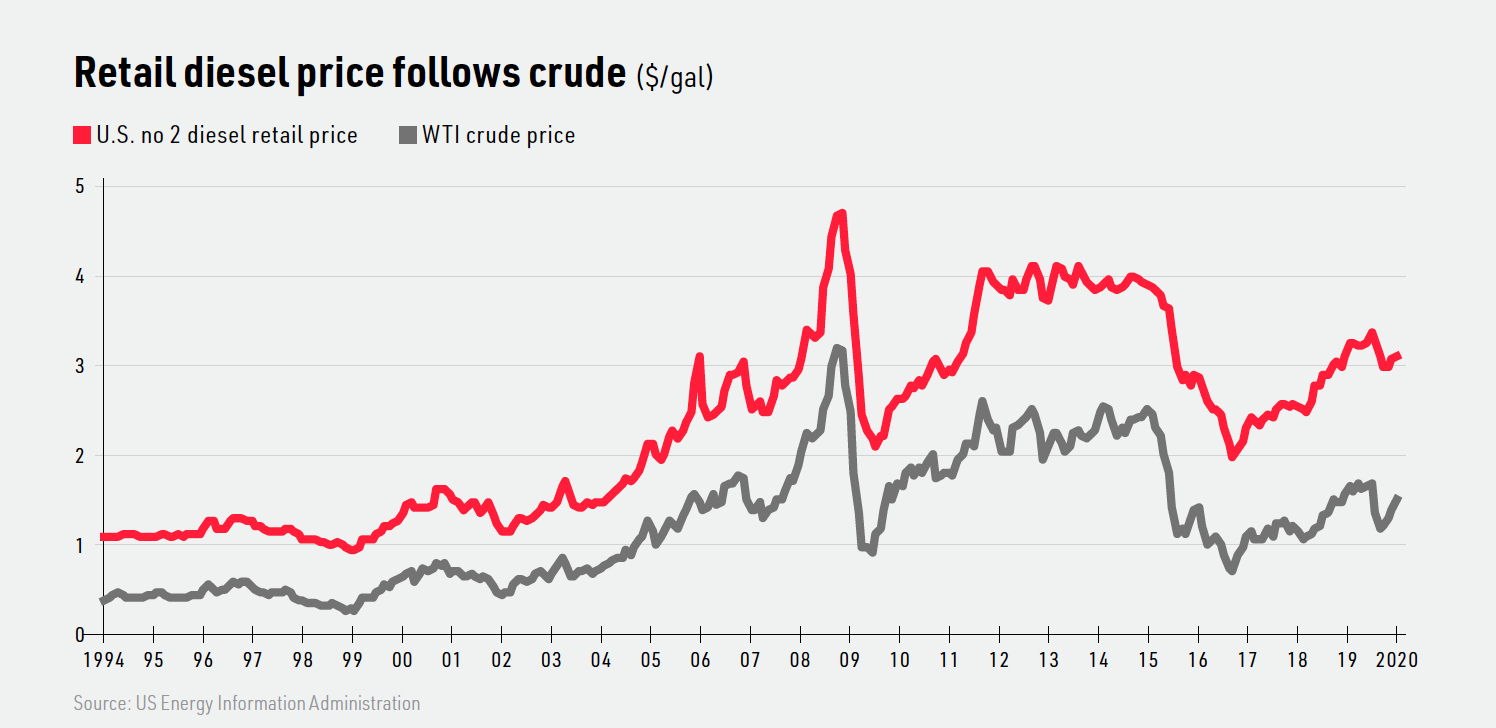

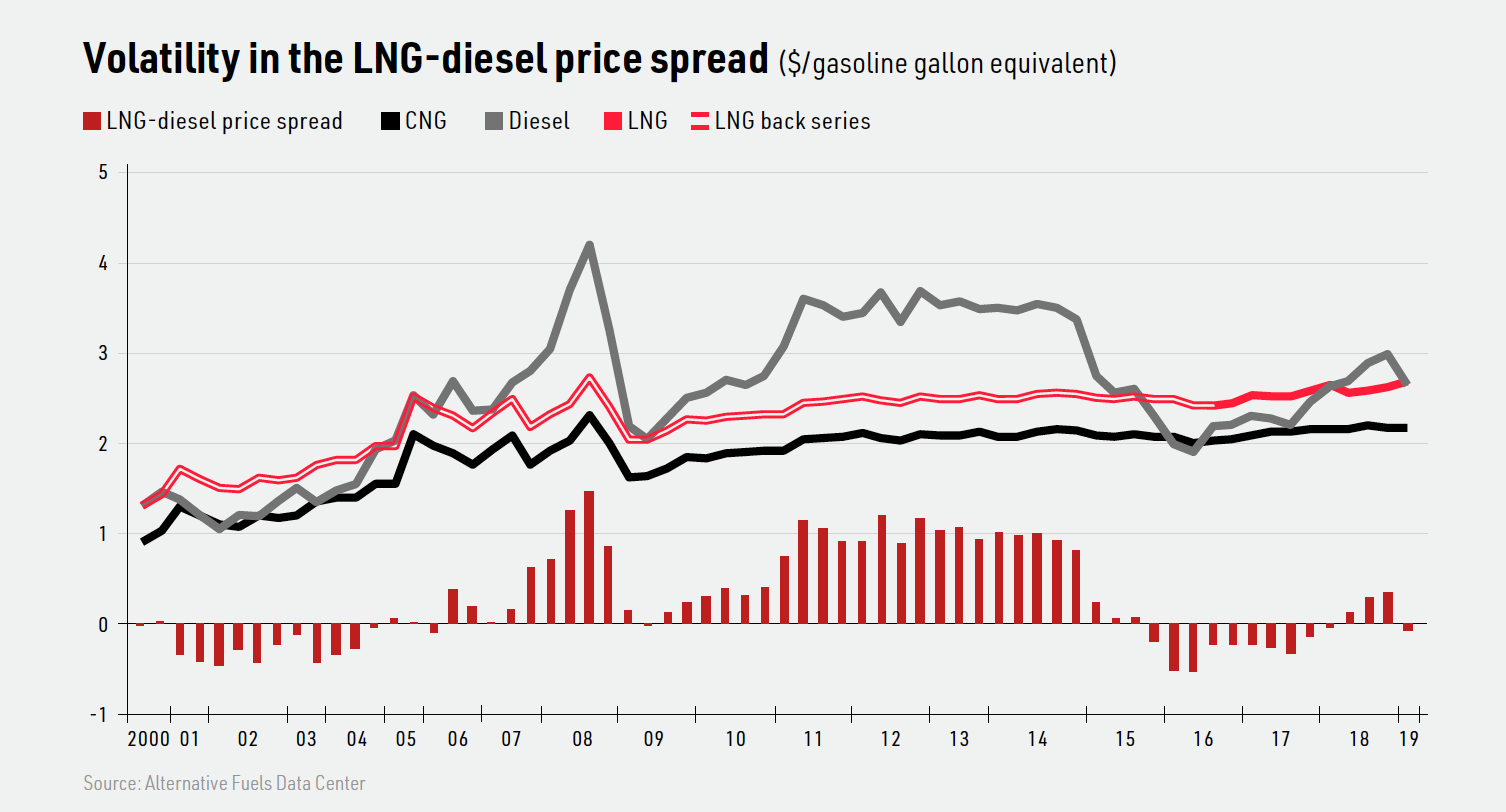

Alternative retail fuel prices provided by the AFDC shows that the price incentive for LNG is by no means constant, not because of fluctuations in the price of LNG, but because of the volatility in oil prices. According to the US Energy Information Administration, 49% of the retail price of diesel in the US comes from the cost of crude oil, with the remainder made up of more stable elements -- refining (15%), distribution and marketing costs (18%), as well as state and federal taxes (18%).

The AFDC has only tracked LNG as a transport fuel since July 1, 2016. While there is some variation in the differential between CNG and LNG prices, taking an average for the period in which the data is available and extrapolating backwards provides a longer time series comparison of diesel versus LNG prices on a gasoline-gallon equivalent (GGE) basis.

Gas stability versus oil volatility

US natural gas prices have been very stable since 2009, owing to the expansion of US shale gas, in large part as an associated by-product of shale oil. This suggests LNG prices should be also be stable and low in the years ahead.

The price of US retail LNG is formed by the price of feedstock – roughly the Henry Hub gas price, although Permian basin gas prices are currently significantly lower – plus the costs of small-scale liquefaction, distribution, handling and storage, which, all in, is much higher than the price of bulk LNG traded internationally.

However, for stability in a price spread, both partners have to tango. Crude prices have been volatile, with retail diesel prices on average higher than retail LNG in the US, but dropping below LNG for extended periods pre-US gas price stability from October 2000 to March 2005 and post-US gas price stability from July 2015 to January 2018.

An LNG truck bought at the beginning of 2009, now reaching the end of its life, would have experienced an average $0.40/GGE advantage to a diesel truck. Based on 100,000 miles/year and fuel efficiency of 5.5 miles per gallon that implies a fuel saving of about $73,000 over 10 years, which would not in fact have offset the additional capital cost of near 80% at the time of purchase for an LNG truck. It would only just have offset the capital cost after just under 9 years based on the European example of 35% additional capital cost in 2017.

The difference in capital cost can be expected to narrow as more LNG truck models are offered to the market and production volumes increase, reinforcing LNG’s long-term fuel cost advantage, but the inescapable fact is that choosing LNG over diesel – when considering nothing other than the bottom line – is not a decision free of price risk, even if the stability of US gas prices is a benefit in and of itself for transporters.

LNG-diesel price spread outlook

At least in the short term, most forecasts suggest that diesel will become a more expensive part of the barrel, mainly because of the International Maritime Organisation’s impending rule on the sulphur content of bunker fuel, which comes into effect January 1, 2020. While many ships are fitting scrubbers so they can continue to use HSFO, many will switch to limited supplies of the new 0.5% sulphur fuel oil or marine diesel oil._f300x384_1560761033.jpg)

On the other hand, if it weren’t for a combination of US sanctions on Iran, internal crisis in Venezuela, and the output restrictions on crude oil production currently imposed by Opec and other major producers such as Russia, there would be a lot more crude oil sloshing around world markets, adding to the rapid rise in US shale oil production of the last two years. If it all came back to the market, diesel prices would drop back below retail LNG as road transport fuel.

Perhaps the long-term guarantee of a favourable LNG-to-diesel price spread is that the member states of Opec are no better positioned now to suffer low oil prices in terms of the budgetary positions than they were 10 years ago. They are therefore likely to continue to limit oil supply in support of an elevated rate of return on their production. At the end of the day, putting US LNG in your tank is a hedge against Opec.