LNG: the prisoner’s dilemma [LNG Condensed]

Anglo-Dutch major Shell announced in February that its Prelude floating LNG (FLNG) vessel offshore Australia would enter a period of maintenance, following a power outage earlier in the month. Meanwhile, press reports have emerged that Qatar will delay choosing partners for its massive planned LNG output expansion of the North Field until possibly the end of this year.

Both might be taken as signs that the supply side of the LNG industry is starting to blink in the face of what is a perfect storm – fast-rising supply combined with weaker-than-expected demand growth as a result of two successive mild northern hemisphere winters and then the coronavirus.

In opportunistically bringing forward a period of maintenance to coincide with a period of low margins, Shell is acting very much as an oil refiner would.

Supply glut extended

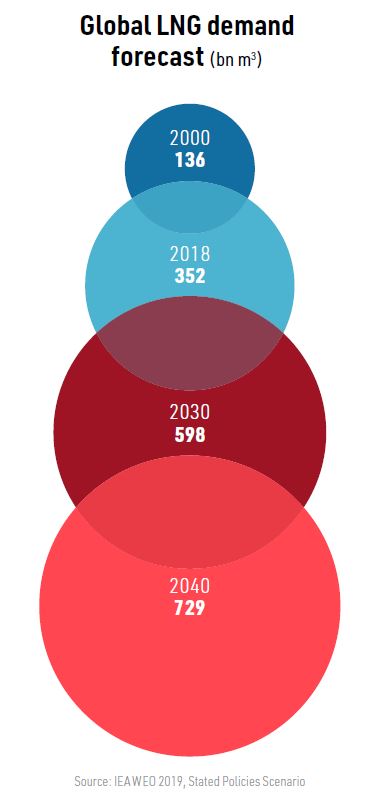

According to Shell’s latest annual LNG outlook, published in February, financial investment decisions (FIDs) on multiple large new liquefaction projects over the past 18 months will extend the period of LNG oversupply from the early 2020s into the mid-2020s, with the exact timing of Qatar’s planned 46mn mt/yr expansion a major wildcard.

Yet “we expect equilibrium to return, driven by a combination of continued demand growth and reduction in the new supply coming on-stream until the mid-2020s,” the company said, referring to forecasts which see LNG demand doubling to 700mn mt/yr by 2040.

The statement is questionable on two related grounds.

First, the idea of market equilibrium is more theoretical than real; markets are in a constant state of flux moving to or away from equilibrium -- they tend not to reach this happy point and stay there for any length of time. Second, a reduction in new supply coming on-stream until the mid-2020s, which will determine the supply/demand balance in the late 2020s, is by no means certain.

Anticipatory behaviour

LNG investment on the supply side is decidedly lumpy and, in terms of behaviour, herd-like. Only two years ago the demand/supply gap looked positive for new investment coming on-stream in the early 2020s, based on FIDs which needed to be taken at least five years previously.

When conditions looked good for one project, they looked good for a lot of projects and there is no shortage of potential new liquefaction schemes. The result was a stampede, as Shell notes, triggering FIDs for 71mn mt/yr of new capacity, eradicating the supply shortfall of the early 2020s and pushing the point of theoretical equilibrium back into the mid-2020s.

But who is to say history will not repeat itself? The long-lead time required for large-scale LNG means companies have to commit early. Other companies follow -- not to miss out on the opportunity -- and all eventually suffer as the industry as a whole over-commits based on individual decisions, each of which appears rational at the company level.

Cartel benefits

Lessons can be learned from the oil market’s busts and booms, which have been tempered by the role of Opec in stabilising oil supply.

This is not to advocate the creation of a gas cartel, but oil prices, while badly hit by the economic fallout of the coronavirus, are not suffering as badly as LNG because the Opec+ group of producers have taken more than 1mn barrels/day of oil production off the market -- in addition to the supply hits delivered by social and economic crisis in Venezuela and US sanctions on Iran.

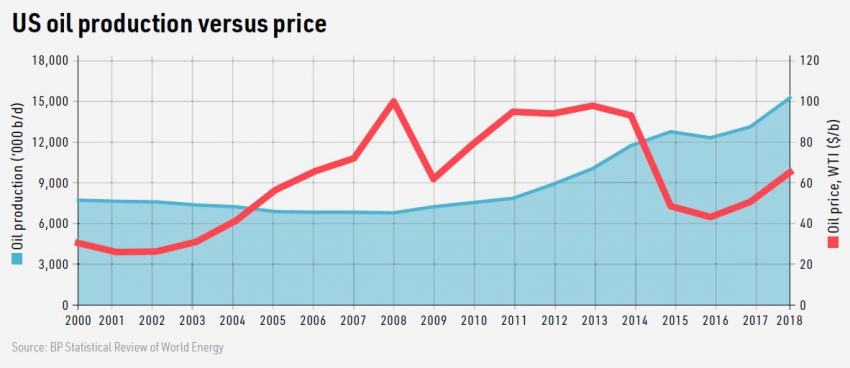

The downside for the Opec+ group is that this policy of restraint sustains the US shale oil boom beyond what market forces might dictate and they lose market share to their competitors. On the plus side, in the short term, they gain price support from what is, in effect, a form of supply-side flexibility.

But while it might work to a degree for oil producers heavily dependent on oil revenues for short-term budgetary needs, it doesn’t work out quite so smoothly for the gas industry, which, as its LNG sector has gained prominence and moved in a less oil-dependent direction in terms of pricing, has had a tendency to overstate the decoupling of oil and gas production upstream.

Oil/gas connections

In supporting oil prices and sustaining the US shale oil boom, Opec’s cartel behaviour/supply-side flexibility also sustains US shale gas production because almost all shale wells produce a combination of liquids and gas. A significant number of US LNG projects based in the US Permian basin are predicated on the basis that the cost of feedstock gas will be virtually nil, if not negative. This includes Tellurian’s Driftwood Project, which Petronet was expected to commit to during US president’s Donald Trump’s visit to India in late February.

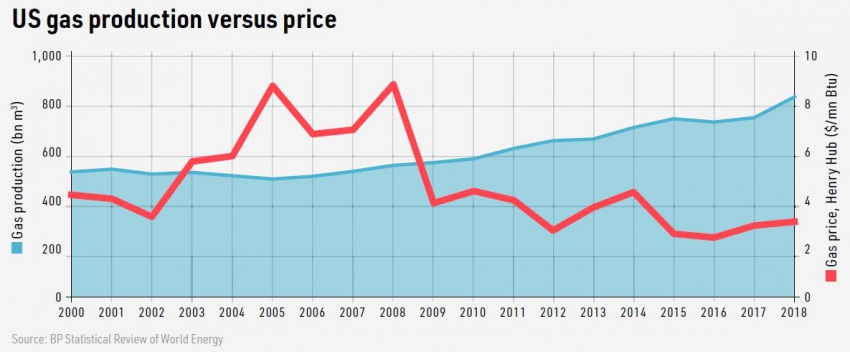

It is US shale oil production which explains the apparent anomaly of sustained low US gas prices combined with near continuous production growth over the last decade.

Similarly, Qatar’s decision whether and at what speed to move ahead with the North Field expansion will in large part be determined by the value of the condensates it produces alongside the gas, which in turn is a function of the oil rather than LNG price.

Opec -- an imperfect cartel made more imperfect by the rise of US shale oil -- has an insoluble free-rider problem, but the impact of the bonus that delivers to non-Opec oil producers washes back into the gas market, where there is no cartel to show supply-side restraint.

This highlights fundamental differences between the two commodities, illustrating why LNG is not the new oil.

LNG production is not dominated by large national state oil companies and LNG revenue is not the budgetary life-blood of a large number of nations. Nor does gas have a near monopoly in the form of transport demand, where oil’s dominant position is still defying erosion from LNG and electrification.

To generate ‘super profits’ – an excess over and above normal returns -- the oil industry required a prior period of chronic under-investment. This was the case in the late 1990s, which led, in the mid to late 2000s, to the steady rise in oil prices to unprecedented levels above $100/barrel.

This followed a period in which Opec held large surplus capacity, which deterred investment, and in which forecasters failed to foresee the pace of Chinese industrialisation and its impact on oil demand. There was therefore neither incentive nor signal for anticipatory investment.

High LNG spot prices in 2016 and 2017 were also the result of a lack of earlier investment and a misjudgement of Chinese demand growth, combined with cold northern hemisphere weather.

It might seem an odd conclusion to reach, but everyone getting forecasts wrong pays better than when everyone gets them right.

Stabilising supply

How then can LNG producers stabilise the market from the supply side, if at all?

Bringing forward maintenance is an option long used by the refining industry, but one that has limits. Shutting in production is another, but here LNG’s lumpy nature makes it much less flexible than oil. Floating storage is one option, but depends on cheap shipping, while LNG in storage suffers from boil off or the consumption of energy required for on-board re-liquefaction.

A Permian basin oil producer can lock down stripper wells, pull back from high-cost heavy oil operations or suspend completions on shale wells until prices revive, or even enter Chapter 11 restructuring, but shutting in an LNG mega-train – a mid-stream rather than upstream asset -- with contractual supply obligations is a much more serious step for an individual company or joint venture.

The issue of supply-side flexibility in the LNG market suggests that modular LNG developments based on multiple small-scale trains could prove a more resilient and stable investment model than large-scale developments.

Not only are the investment commitments more flexible and smaller at any one time, even if just as large over an entire project life-time, but if the worst comes to the worst and production has to be shut in, it can be done so on a more flexible basis in either small or large increments.

Contrast for example, Rovuma and Mozambique LNG on the one hand with BP’s Tortue LNG on the other. Rovuma and Mozambique are both big onshore developments weighing in with capacity of 15.2mn mt/yr and 12.88mn mt/yr respectively. Both will employ two mega-trains each constructed simultaneously and coming on-stream within six months of each other.

Tortue LNG, which has progressed more rapidly than either of the Mozambique projects, may appear relatively unambitious at first glance, targeting a single 2.5mn mt/yr train in the first phase.

However, Phase 1 will put in place the infrastructure to accommodate a further three floating LNG trains of the same size, so potential capacity is 10mn mt/yr. BP is also taking all of the output from the first train into its own portfolio, while the Mozambican projects rely on some equity partner offtake, more so in the case of Rovuma LNG than Mozambique LNG, but also sale and purchase agreements with third-party customers.

Given the downturn in spot LNG prices and uncertainty prevailing over how long the supply glut will last, BP’s modular development looks decidedly more flexible.

The company has committed less capital upfront and, once Phase 1 is complete, its ability to increase production should be quick in LNG industry terms, particularly given shipping companies’ willingness to convert LNG carriers to FLNG vessels on a speculative basis. Equally, should production have to be shut in, the hit would be relatively small, incremental based on all four trains being installed, and contractually simpler.

Long-term competition

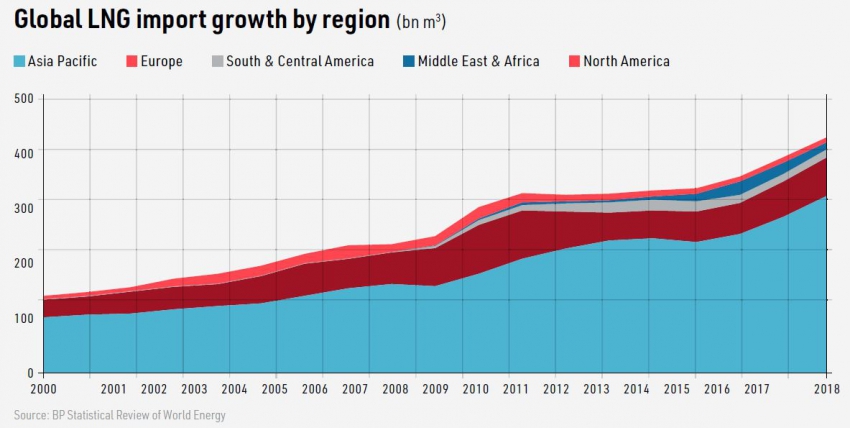

In its annual LNG outlook, Shell expresses long-term optimism about LNG demand growth, in particular the essential role it can play in reducing greenhouse gas emissions as a result of coal-to-gas switching.

LNG’s relatively high price in comparison with domestically-produced gas, for example, in south Asia, has been a barrier to its adoption. Low spot prices for LNG mean countries like India, Pakistan and Bangladesh can absorb more imported gas without incurring crippling subsidy bills as a result of their apparent inability or unwillingness to remove subsidies in sectors such as electricity generation and fertilizer production. Whether transition or destination fuel, the early accessibility of LNG will encourage gas-for-coal displacement, while renewable energy capacities are built up.

This growth in LNG consumption will be accompanied by bigger seasonal swings in demand as a result of growing baseload demand, and it is here that LNG suppliers can hope to find the booms to offset the busts. Long-term demand forecasts tend to focus on a central range and ignore potential seasonal demand swings.

Anticipatory investment, resulting in herd behaviour, has no obvious remedy, and is indicative of a market working well, providing competition and a commodity at the lowest cost to consumers – a situation which supports the optimistic demand growth projections on which LNG investment is based.

But in what is already a highly-competitive market, companies need both to bear down on costs and develop more flexibility on the supply-side in order to smooth the investment cycle and make production more reactive to both increases and shortfalls in expected demand.

In this, producers need to accept more risk to gain more supply-side control, as they have done via the growing trend for upstream companies to offtake LNG into their own portfolios and provide bottom line financing for new LNG projects.