[NGW Magazine] What’s happening with CCS?

This article is featured in NGW Magazine Volume 2, Issue 15

Carbon capture & storage is the necessary adjunct to fossil fuel use, in industry as in power, if the Paris Agreement on limiting global warming has a hope of being realised.

The demise of carbon capture and storage (CCS) has been in the news since 2007. Since then periodically articles appear with news about ‘a blow to CCS’. The headlines at the start of July in Europe were “another blow to CCS, as Engie and Uniper bow out of Dutch project” and in the US “coal on limited lifespan as CCS hopes go up in smoke.”

And yet CCS is still considered essential to the continued consumption of fossil fuels in a world where the Paris Agreement on climate change is seeking to limit the average temperature increase to 2 degrees Celsius.

The first week of July was difficult for CCS. First, in Europe Engie and Uniper announced their intention to withdraw from a test project to capture and store CO2 generated by a major new coal plant, Maasvlakte (pictured) in Rotterdam port in the Netherlands, known as the Rotterdam Road project. This was followed a few days later by the cancellation of the Kemper CCS project in the US.

Maasvlakte power plant in Rotterdam port

_f400x183_1501187683.jpg)

Image credit: Borgel Elementbau GmbH

The European environmental non-governmental organisation, Bellona Foundation, was not surprised by the Engie/Uniper cancellation, observing that the two companies showed little desire to commit to CCS development.

But the Dutch minister of economic affairs, Henk Kamp, confirmed that this withdrawal from the Rotterdam Road project did not impact the government’s resolve to develop large-scale CCS demonstration projects. He went on to say the Dutch government is serious about industrial decarbonisation and CCS.

Officially, Engie and Uniper will scrap their plan September 15. The minister says the remaining time will be used to consider possible alternatives. He believes most of this work will be done by the Rotterdam port authority, the gas transport system operator Gasunie and energy knowledge company EBN. They are investigating the possibility of developing a collective CO2-grid along the entire port area.

There was also bad news from the US. On July 5, the US energy market’s flagship clean-coal and CCS project was also cancelled. The US energy utility Southern Co announced abandoning the Kemper coal gasification and CCS project, after costs sky-rocketed from $1.8bn to more than $7.5 bn.

The CCS element was not the main reason for this escalation but nevertheless, these cancellations have been claimed to deal another serious blow to the prospects of CCS, especially in terms of the lifeline it offers for fossil fuels and coal-fired power as the world shifts to low-carbon energy generation.

Calls for scrapping coal-fired power generation

These cancellations have come at a time when a group of leading scientists has called for the construction of new coal generators to cease within three years. In an article in Nature magazine, more than 60 scientists and prominent leaders, including the former United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change secretary Christiana Figueres, say the world has three years to set emissions on the right course.

Their argument shows the paths to meet the Paris ‘well below 2 degrees C’ target, taken in this case to be 1.5 degrees C. The latest time by which emissions will have to start falling, termed as the ‘carbon crunch’, has to be 2020 if gradual descent of the global economy is to be achieved, allowing it to adapt smoothly. If this is delayed to 2025 it allows little time for adjustment.

Greenhouse-gas emissions are flat and are already decoupling from production and consumption. But in order to start falling, the article states that: ‘No coal-fired power plants are approved beyond 2020, and all existing ones are to be retired.’ It also calls on carbon-intensive heavy industry to develop and publish plans for increasing efficiencies and cutting emissions, with a goal of halving emissions well before 2050, but it does not suggest how.

The report itself recognizes that these goals may be idealistic at best, unrealistic at worst.

And this is where the challenge lies. An article in NGW Vol 2 #12 addressed global coal demand and the conclusion was that coal will remain an important contributor to global primary energy well into the future, contributing as much as 24% of global primary energy by 2035. Because of its low price and its wide availability, coal maintains a strong position in the world’s primary energy mix, particularly in India and China. But even in Europe coal consumption is stubbornly remaining a significant part of future primary energy. Cheap coal is hard to beat and it is too early to call its demise.

As IEA pointed out in a recent article, “we can’t let Kemper slow the progress of carbon capture and storage.” But to suggest new and in many cases highly efficient coal-fired power generation plants could simply be shut down in a timeframe consistent with climate goals fails to appreciate the political, social and economic realities, especially in Asia.

Need for CCS

The answer comes back to the adoption of CCS. Deployment of CCS offers an important way to address fossil fuel emissions meaningfully and effectively. CCS will be of importance where coal will continue being used into the future. And this not as much in the EU or the US, where the recent cancellations took place, but mostly in Asia. If wishing coal to go away does not work, then adoption of CCS may be the best option to combat out-of-control CO2 emissions. But, something often overlooked is that, in addition to power, CCS is the only clean technology that can decarbonise industry.

It is for this reason the Eighth Clean Energy Ministerial meeting, organised by the world authority on CCS took place in Beijing June 8. It identified CCS as key to decarbonisation of coal and gas and in broader industry applications. China has ramped up its efforts to develop and use CCS to decarbonise its coal-fired plants.

It is also of importance to the oil and gas industry, where CCS offers an important way to help fossil fuel assets recover their investments and minimise the risk of stranded assets in a low-carbon transition.

Some of the oil majors – with notable exceptions from the US – recognised this and in November last year, as part of their Oil and Gas Climate Initiative, they created a $1bn investment fund to develop technologies to promote renewable energy. The fund also focuses on ways to reduce costs of CCS technology, with specific emphasis on capturing carbon dioxide emissions produced from fossil fuel burning plants and re-injecting them underground for absorption in depleted reservoirs.

The International Energy Agency (IEA) and the International Renewable Energy Agency (Irena) issued in March a joined report on global energy transition entitled The Perspectives for the Energy Transition: Investment Needs for a Low-Carbon Energy Transition.

One of the key conclusions they reached was that without CCS use of coal would need to decline by two-thirds and some fossil fuel assets will not be utilised and will become or remain stranded. Deployment of CCS offers an important way to help fossil fuel assets recover their investments and minimise stranded assets in a low-carbon transition.

Bellona goes further, taking the position that without CCS it will be impossible to combat global warming. It says that CCS is not just for the power sector. A large part of emissions of energy intensive industries such as steel, cement and glass production, are inherent and cannot be tackled by any other means than CCS. CCS is not in opposition to renewables. Its deployment is in opposition to unabated fossil fuel use and out-of-control CO2.

The future

Even though it was not CCS that caused the cost escalation, the Kemper experience in the US could create a legacy with damaging implications for the future of CCS and clean-coal technology.

However, those who recognise the importance of CCS in supporting a manageable and sustainable transformation of the global energy sector, consider it vital to continue efforts to tackle emissions from the world’s coal-fired power fleet. As the IEA states, the role of CCS goes well beyond coal and the power sector, also into industry and natural gas processing. It is one of few technology options capable of achieving deep emission cuts across industrial sectors.

CCS Association CEO Luke Warren said that despite the setbacks, there is plenty of room for optimism for the future of CCS and its ability to contribute to the global fight against CO2 emissions. He added: “Whilst the decision to suspend work on the Kemper CCS project is obviously disappointing, it is important to emphasise that there are large-scale CCS projects already in operation – such as the Boundary Dam and Petra Nova projects.”

The world’s first retrofit CCS project started operations in 2014 at the Boundary Dam power plant in Canada, and demonstrated CCS technology.

However, the successful commissioning of the world’s largest commercial-scale post-combustion carbon capture facility at Petra Nova coal-fired power generation project in Texas earlier in 2017 (pictured), represented an important step in advancing the commercialisation of technologies that capture CO2 from existing power plants. US Energy Secretary Rick Perry in opening the project said: “I commend all those who contributed to this major achievement. While the Petra Nova project will certainly benefit Texas, it also demonstrates that clean coal technologies can have a meaningful and positive impact on the Nation’s energy security and economic growth.”

Petra Nova coal-fired power generation plant, with CCS

.jpg)

Image credit: Petra Nova

Countries around the world are pushing ahead with CCS in both power and industrial sectors, demonstrating the importance of CCS to cost-effectively decarbonise energy intensive industries, power and even heat. If the world is to deliver the 2 degrees C goal, then CCS must be a significant part of the solution.

In fact, there are now 17 large-scale CCS projects operating around the world, with four more due to be commissioned this year and next. The IEA states that it is vital that we continue to grow this portfolio and at a much faster rate. China is also embracing CCS, having just announced construction of its first large-scale CCS project in its coal/chemicals sector and with seven further projects under early development.

Retrofitting existing coal-fired power stations with CCS in China represents a significant opportunity to manage CO2 emissions while continuing to use its vast coal-based infrastructure that has been expanding rapidly in recent years. In India adoption of CCS has started, but it is at an early stage.

In the United Arab Emirates, captured CO2 is being injected into mature oil reservoirs to enhance recovery at the Al Reyadah facility. Speaking at the WFES conference earlier in the year, Arafat Al Yafei, CEO of Al Reyadah, said: “Al Reyadah is proving carbon capture utilisation and storage is commercially viable and a win-win solution for industry and the environment. It is providing a launch pad to take this technology to the next frontier and demonstrating these projects can thrive on synergies between different partners… it is a prime example of how state-of-the-art technology can be integrated with traditional energy to create efficiencies and optimise resources. Our objective is not only to satisfy ADNOC’s demand for CO2, in support of its enhanced oil recovery plans, but also to liberate valuable natural gas to meet rising demand.” Before this project, gas was being injected into the reservoir to enhance oil production, as is common with many other ageing oil-fields worldwide.

Speaking at the same conference, the Global Carbon Capture and Storage Institute’s advisor on Europe, Middle East and North Africa John Scowcroft said: “As CO2 emissions from industrial sources continue to rise, it is patently obvious that CCS is the most realistic carbon mitigation alternative within reach of industrial processes. When governments recognise the challenge of transforming industrial processes for a low-carbon economy, we will be much closer to reaching the almost 4,000mn metric tons/yr of CO2 that need to be captured by 2040 to meet climate goals.”

A related, pioneering, project has just been started by Statoil in Norway, on behalf of Gassnova the state enterprise for carbon capture and storage, to monitor and evaluate the potential development of a CCS project on the Norwegian continental shelf.

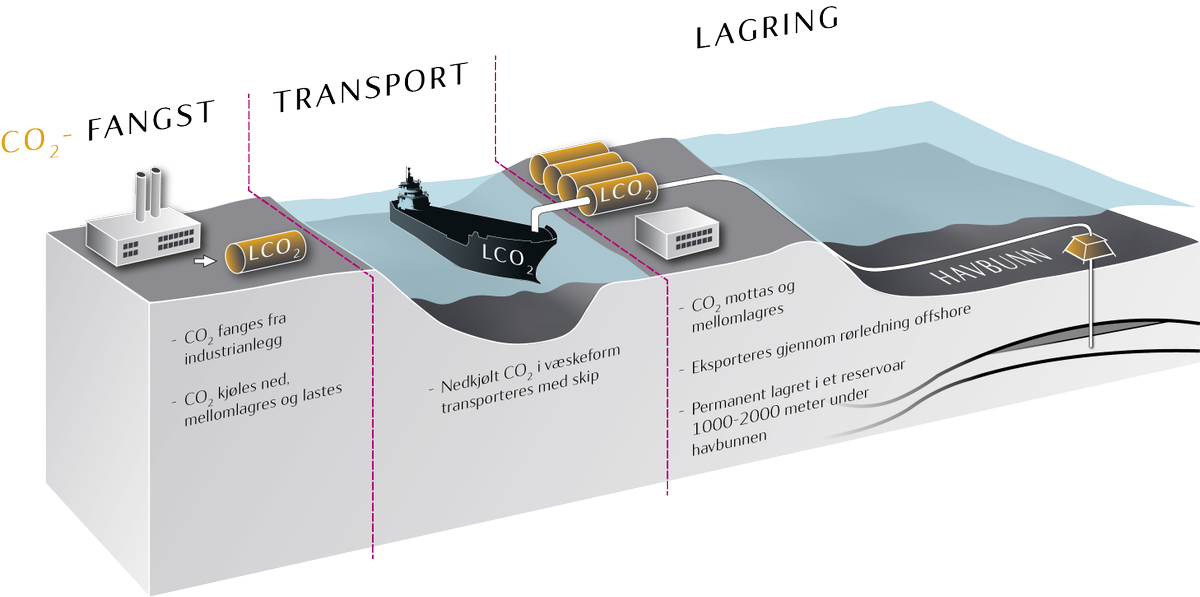

The project aims to capture, compress and temporarily store CO2 from three industrial plants, and then transport it by ship from the capture area to an onshore receiving facility in Norway. The CO2 will be pumped from the ship to tanks onshore and then be exported via offshore seabed pipelines to several injection wells on the offshore Troll field (pictured). Gassnova is a demonstration of Norway’s commitment to lead in terms of technology research, development and demonstration and contribute to the realisation of CCS technology in industrial plants.

Statoil’s CCS project in Norway

Graphic credit: Statoil

Emissions from the industry sector account for about a quarter of global CO2 emissions, and CCS is one of few technology options available for meaningful emissions reductions. Retrofitting CCS needs to become a key strategy in many regions, and is something that should be targeted with early CCS deployment efforts.

Speaking at the Japan CCS Forum in Tokyo end of June, Juho Lipponen, head of the CCS Unit at the IEA, said the new mapping to 2060 and beyond showed that 32% of energy technology had to be backed up by CCS if carbon neutrality is to be achieved by then. However, wider CCS deployment requires comprehensive policy packages and policy support.

But there are challenges. The cost-effectiveness of CCS still needs to be demonstrated through the evaluation of new projects as they become operational. The price of carbon in Europe remains woefully low, compared with the cost of CCS, and rewriting the carbon trading rules and changing the quotas is a politically charged issue. However, with coal and fossil fuels expected by most substantiated forecasts to be contributing significantly to the global energy mix in the longer-term, CCS is – especially outside Europe – considered a serious and realistic option to contribute to the global energy transformation.

Charles Ellinas