[NGW Magazine]: Oman gas: bridging the gap

This article is featured in NGW Magazine Volume 2, Issue 15

With first gas from its vast Khazzan field due in the next few months, Oman is still pursuing other ways of safeguarding its energy supplies including a pipeline from Iran and other imports.

2017 is promising to be a momentous year for Oman gas, with Phase 1 of BP’s block 61 tight gas field slated to start production in September, ahead of the UK major's earlier predictions. In addition, Phase 2 was formally sanctioned in March this year.

This is very timely given the impending shortages of gas and the problems between Oman and Qatar, which exports about 2bn m³/yr of North Field gas to the United Arab Emirates and Oman through a subsea pipeline operated by Dolphin Energy. Even though gas continues to flow normally, escalation of tensions could be of concern. A potential shutdown of the pipeline would cause a severe problem and hit Oman’s LNG exports.

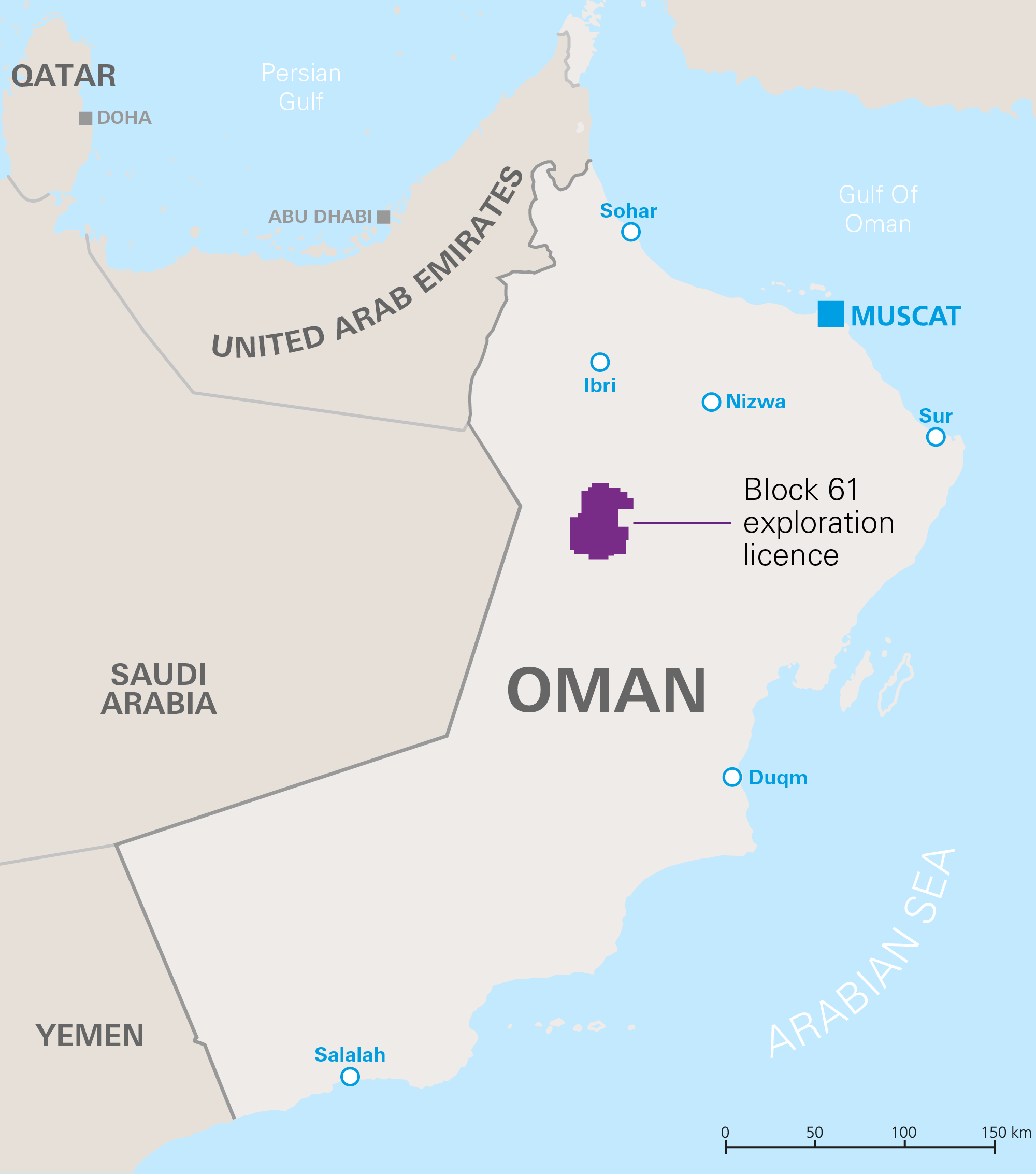

Khazzan is a tight natural gas field discovered in 2000 and is being developed by BP in block 61, 350 km from the country’s capital, Muscat. The field is estimated to contain over 2800bn m³ gas in place. The operator is BP with 60% interest, with Oman Oil Co E&P holding the remaining 40%. BP has had an upstream presence in Oman since 2007. Khazzan will be one of BP's seven key projects for 2017.

Khazzan

Map credit: BP

Phase 1 of the development of block 61, the Khazzan field, was sanctioned in December 2013 and development of the field started early 2014. It is expected to produce 10bn m3/y and 25,000 b/day of condensate.

Construction is proceeding on time. In May this year BP said that it completed the successful drilling and completion of the 50th well. As a result, the Oman oil ministry confirmed earlier in July that it is expecting to start production from train 1 early September 2017 with all gas to be allocated to the domestic market. Train 2 is expected to be in operation early 2018.

BP Oman president Yousuf al Ojaili confirmed in April that the project was at the pre-commissioning stage and that some of the utility projects have already been commissioned.

Khazzan gas-field facilities

Image credit: BP

Block 61 drilling programme is on track. About 325 wells eventually will be drilled to a depth of 5 km, required to reach the sandstone reservoir, over the project’s full field development period of 15 years. BP said development of the field involves horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing techniques to stimulate production and exploit it fully. This is one of the largest unconventional tight gas projects in the Middle East.

Khazzan drilling rig

Image credit: BP

Ghazeer gas-field

In November 2016 BP and the oil ministry signed a deal to extend the licence area and agreed to proceed with Phase 2 of the project, known as the Ghazeer field. This was ratified by the government in March this year, adding a further 1,000 km2 to the south and west, bringing the total block 61 licensed area to 3,950 km2.

Following ratification, al Ojaili said: “The issuing of the Royal Decree is a momentous occasion for BP Oman as we continue the development of Block 61 with our partner OOCEP. We are on track to deliver Khazzan first gas later this year and, in parallel to that, we will be driving ahead the field development of Ghazeer. Our knowledge and experience from the Khazzan field will help develop the Ghazeer field with the greatest efficiency.”

The extension allows Phase 2 to proceed, accessing additional resources in the area that have been identified through earlier drilling and enabling further development of the gas reserves in block 61. Around 1 trillion m³ of accessible gas are estimated to exist at Ghazeer and 125 wells will be drilled over the project lifetime. Drilling has already started. Phase 2 will require a third train to be added to the block 61 complex, and it is expected to deliver 5 bn m³/yr gas by 2020, as well as additional condensate.

This expansion will build on BP’s work on the first phase. The two phases are expected to develop about 300bn m3 of recoverable gas resources. They involve construction of a three-train central processing facility with associated gathering and export systems at a total cost of $16bn over a 15-year period. At the peak of construction, there will be 8,000 to 10,000 people working within Block 61.

High priority

Oman and BP have given high priority to block 61, reflecting the acuteness of the country’s impending gas shortage as the government attempts to meet increasing power generation demand, while at the same time pursuing large-scale gas-intensive industrial developments.

The combined output form Phases 1 and 2, expected to exceed 15bn m3/yr, will be the major source of energy for the Omani economy for decades to come, increasing Oman’s current total domestic gas production by over 40%. In addition to contributing to Oman’s economy, full development of the field will add substantially to Oman’s proved natural gas reserves, which in January 2016 totalled 690bn m3.

Block 61 facilities have already been tied into Oman’s main gas grid. Al Ojaili said that gas can also go to Oman LNG for export, but this would require authorization by the government. This was subsequently confirmed by Salim Al Aufi, Undersecretary at the ministry, who said in July: “The local market will have a share of the gas produced from Khazzan gas field. Some quantities will be also exported to be used as feedstock for Oman LNG.”

LNG exports

Oman LNG exports LNG from three liquefaction trains at Qalhat, south of Oman, with total capacity of 14.5bn m³/y. The company was formed by the merger of Oman LNG, with two trains, and Qalhat LNG, with one train, in 2013. The main shareholders are the government with 51%, Anglo-Dutch Shell with 30%, FrenchTotal – also a 24.5% shareholder in Dolphin Energy – with 5.54% and Korea LNG with 5%.

Oman’s natural gas production in 2016 was close to 39bn m³, with an additional 2bn m³ imported from Qatar. The Oman LNG 2016 Annual Report published in April states that 11.2bn m³ was exported as LNG, up 4% on 2015, with most exports going to Japan and South Korea. However, revenues in 2016 were $1.9bn, down from $2.6bn in 2015, reflecting the protracted global downturn. As a result of the shortage of gas, only 77% of Oman’s LNG export capacity is being used.

Oman LNG

Courtesy: Oman LNG

Rising domestic demand for natural gas (Figure 1) is increasingly limiting the volumes available for export. LNG exports reached a peak of 12.5bn m³/yr in 2006 and 2007, but these have been declining from 2008 onwards (Figure 2). As a result, Oman has been forced to import gas from Qatar through the Dolphin Pipeline, about 2bn m³ in 2016, necessary to meet the rising level of domestic natural gas consumption.

Gas demand for power generation is expected to rise from 8bn m³ in 2016 to 10bn m³ by 2020, according to the Oman Power and Water Procurement Company. In addition, Business Monitor International forecasts that overall domestic demand will grow at an annual rate of 7.3% between 2016 and 2025. These will add to the challenge for Oman to continue developing new reserves.

Interestingly, despite the huge potential, renewables provide less than 1% of Oman’s electricity, which is heavily subsidized disadvantaging the competitiveness of renewable energy technologies.

Oman is seeking to industrialise rapidly to provide jobs and diversify its economy beyond oil, but these plans could be delayed if gas supplies do not keep up with surging domestic demand. In 2016 industrial projects consumed 23.7bn m³ gas, up 4.6% on 2015.

So despite its proven gas reserves, Oman is considering deploying an FSRU so that it can import cheap LNG. Erwin Mortelmans, commercial director at Duqm Port, said in April: “This is at a very early stage – we look at the concept and we see if it might work in terms of capital investment, versus operating expenses, versus demand in Duqm.” He added “We’re looking at a 150,000 m³ vessel and take it from there.” This could add much-needed flexibility and security to Oman’s energy supplies.

Oman’s gas industry, which includes a growing petrochemical sector and new industrial complexes, is expected to expand significantly in the medium term, requiring more gas, at the same time as the country hopes to increase LNG exports.

In addition to the small amount of gas imported from Qatar, Oman has more than doubled its gas production over the past ten years. Its target is to increase capacity to 60bn m³/yr by 2020. BP’s Khazzan and Ghazeer gas projects are expected to contribute significantly to this increasing need for more gas, but even more may be needed if LNG exports are to be maintained. This is where Iran comes in.

Iran-Oman gas pipeline

Iran has long eyed Oman’s excess LNG production and export capacity as a potential conduit for Iranian gas to the international market. In March 2014, Oman signed a memorandum of understanding with Iran to import 10bn m³/yr through a pipeline under the Gulf of Oman, of which about a third is destined for Oman LNG, but negotiations were protracted without advancing significantly, mostly owing to pressure from US sanctions on Iran.

This project gained momentum in 2016. After international sanctions on Iran were lifted in January – Oman playing a behind-the-scenes role in this – the two countries renewed efforts to implement the project. Iran and Oman have been in discussions to agree the technical and financial details of the project during the past few months.

In an interview late last year, Oman’s oil minister Mohammed bin Hamad al-Rumhy said Oman and Iran were at an advanced stage of designing the pipeline and had agreed on the pipeline route. The pipeline would be financed on a 50-50 basis by Oman and Iran. At the end of November senior officials from Oman and Iran met in Tehran to discuss the export of Iranian gas to Oman. Present at the two-day meeting were representatives of Shell, Total and Kogas, all shareholders in Oman LNG.

According to Platts, following the meeting Shell confirmed that it was a member of the Advisory Task Force of the Iran-Oman gas pipeline project, but declined to go into details, citing confidentiality.

IRNA reported that the meeting examined various scenarios to include Shell, Total and Kogas in the subsea pipeline project. It also reported that the meeting did produce the desired results and that negotiations will continue.

In February this year Oman and Iran signed a new agreement that extends the previous deal and agreed to change the route of the pipeline to avoid waters controlled by the UAE. Present at the meeting were also representatives from Shell, Total, Kogas, Mitsui, and German utility Uniper.

The pipeline will be 260 km long and is expected to be completed two years after start of construction at an estimated cost of $1.2bn. The chosen route circumvents any maritime borders and would not require permission from its neighbour, UAE. Iran and Oman are also considering plans to increase gas supply capacity of the pipeline from 10bn m³/y to 15bn m³/y.

Interestingly, Total, a key participant to this meeting and an Oman LNG shareholder, signed a deal early July to develop Phase 11 of Iran’s South Pars with production capacity of 20bn m³/yr gas by 2021.

Iran and Oman agreed to push ahead with the development of the subsea gas pipeline by 2020. Iran is very keen on this, given the critical importance of LNG to its overall export strategy in the next few years and the rising importance of LNG to the global gas market. Oman is also very keen because of increasing domestic gas demand. In fact, Oman announced late last year that, without new gas, at the latest by 2024, it may have to divert all of the natural gas that it is currently exporting to satisfy this domestic demand.

However, even though Iran said it expects to finalize talks in early March, no further progress has been reported yet. The current spat between Saudi Arabia and Qatar, partly as a result of Iran, and its impact on the region could be a factor in this.

Charles Ellinas