Mega mergers amid a slump in prices: what next for the US gas industry? [Gas in Transition]

The US is currently experiencing low gas prices and, in April, even negative ones in Texas as production outstripped takeaway capacity. Stocks are high, standing at 2.563 trillion ft3 at the beginning of May, 21% above year ago levels and 33.3% above the five-year average.

However, there is substantial optimism that the current glut of gas will be short-lived.

In the meantime, the sector is seeing major consolidation, a common response to lower prices as companies seek to reduce costs and increase efficiency.

Chesapeake Energy and Southwestern Energy will combine to create the biggest natural gas production company in the US, while ExxonMobil closed its $60bn acquisition of Pioneer Natural Resources on May 3, after receiving approval from the Federal Trade Commission. Overall, 2023 was a record year for US oil and gas M&A and the trend continued in the first quarter of this year.

Demand drivers

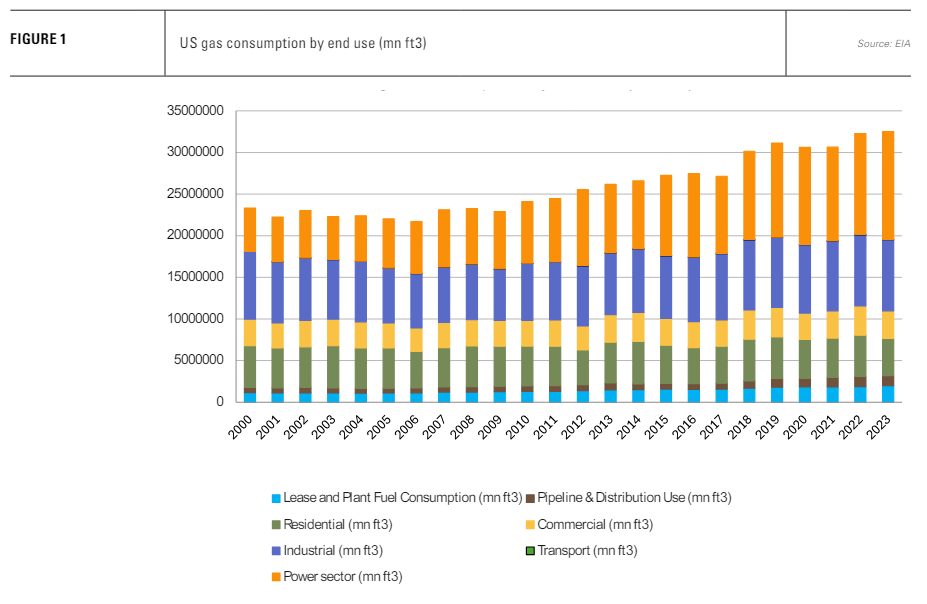

Multiple factors point to further rises in demand for US gas, which is already at a record level (see figure 1).

One is Shell’s LNG Canada project, which, when it starts commercial production in mid-2025, will suck up some 2bn ft3/d of Canadian natural gas, equivalent to 11% of the country’s current production. This is expected to reduce gas available for export to the US.

LNG Canada – a milestone for the Canadian gas industry as it diversifies its export markets away from sole dependency on the US – is expected to be followed by the smaller Cedar LNG (0.4bn ft3/d) and Woodfibre LNG (0.29bn ft3/d) projects, and potentially by two much larger projects Ksi Lisims LNG (1.7-2.0bn ft3/d) and the second phase development of LNG Canada, which would almost double the facility’s capacity.

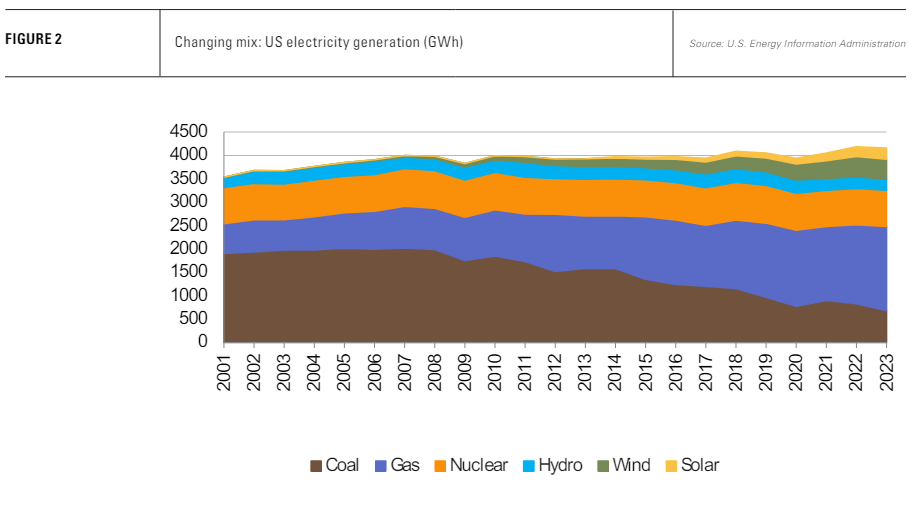

A second factor is that cheap gas spurs domestic demand and the US over the last two decades has undergone a substantial transition from coal-fired generation to gas (see figure 2). Growth in domestic gas consumption has been dominated by gas-fired power generation.

Cheap gas allows power generators to increase their utilisation rates and capture market share from the remaining but still large fleet of coal-fired generators. Consumption of natural gas for electricity generation from all sectors reached 13.2 trillion ft3 in 2023, up from 9.5 trillion ft3 in 2017, even if new gas-fired generating capacity additions have in recent years given way to renewables.

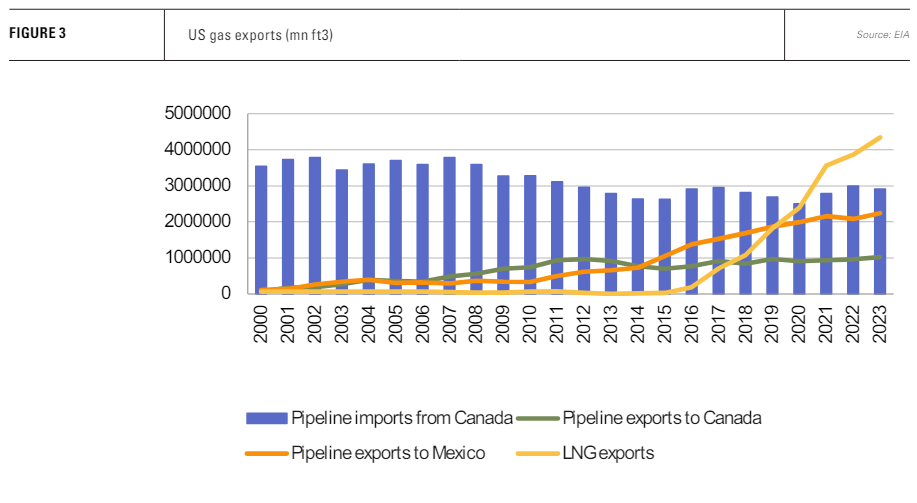

Pipeline exports to Mexico have also been a major source of demand growth, one which is expected to continue. In April, the US Energy Information Administration (EIA) forecast growth of 3% (0.3bn ft3/d), this year for pipeline exports, primarily to Mexico as the Tula-Villa de Reyes, Tuxpan-Tula and Cuxtal Phase II pipelines become fully operational and flows increase via the Sur de Texas-Tuxpan line with the expected start up for Mexico’s first LNG project, Fast LNG Altamira.

As LNG plants in Canada and Mexico start to play a role in consuming North American gas, so too will growth in the US’ own LNG fleet (see figure 3). In addition to existing capacity, Plaquemines LNG Phase 1 and Corpus Christi Stage 3 should load their first cargoes by the end of this year. They should be followed next year by the first two trains of the Golden Pass LNG project. These projects are just a forerunner of larger projects expected to come onstream before 2030.

The weather is another supportive variable at least in the short term, although with plenty of caveats. The current high level of gas in storage reflects an unusually warm year, the result of a strong El Niño effect and climate change. A strong El Niño comes around about once every ten years, and the impact should dissipate this year.

US gas consumption only rose last year because of demand from electric generators, which jumped by 812bn ft3. Residential demand was down almost 500bn ft3, while commercial demand dropped 200bn ft3. Industrial gas demand was flat and industry expansion accounted for an increase in lease and plant fuel and pipeline and distribution use.

However, the ten warmest years since records began all occurred between 2014 and 2023, according to the US National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI). As a result, while it is hard to untangle the impacts of El Niño, climate change and other meteorological phenomena, the former suggests 2024 will be cooler than 2023, but the overall trend of warmer weather will continue.

As a result of increases in both pipeline and LNG exports, the EIA forecasts that net US gas exports will rise by 6% to 13.6bn ft3/d this year and by a further 20% in 2025 to 16.4bn ft3/d. Cheap gas will sustain domestic demand for electricity generation, Canadian imports will be constrained and both pipeline and LNG exports will add to the need for US gas production to continue breaking new records.

LNG over-exposure?

However, all this poses an interesting scenario. The US gas market will become increasingly exposed to the international market for LNG, not just from the large-scale expansion of its own LNG plants, but in terms of available Canadian gas supply and Mexican demand, as the latter also expands its LNG capacities based on US feedstock.

Imagine a downturn in LNG demand – for whatever reason, but the energy transition is an obvious one. The US gas sector would feel a triple blowback via its domestic LNG production, Canada and Mexico, potentially leaving a massive surplus of gas on the domestic US market.

There is also uncertainty regarding the primary driver of US gas demand – electricity generation.

The US is adding renewable energy capacity at a fast rate; 32.4 GW of solar PV capacity in 2023, a 52% increase from 2022, including 22 GW of utility-scale installations. For the first time, solar made up more than 50% of all additions. According to the Solar Energy Industries Association, US solar capacity will quadruple from 177 GW at end-2023 to 673 GW by 2034.

Returning to the weather; if it was a bad year for hydro last year, it was also unexpectedly bad for wind, which saw total generation fall, despite the addition of 6.2 GW of new capacity, owing to slower wind speeds. However, the continued addition of new capacity should sustain the long-term upward trend in wind generation.

Overall, the EIA expects solar generation to jump 75% between 2023 and 2025 to 286 TWh, while wind output increases 11% to 476 TWh. Gas-fired generation will unquestionably have to compete with more renewable capacity. That said, renewable energy sources, including hydro, still only accounted for 22% of US electricity generation in 2023.

The EIA forecasts that coal generation will continue to fall and that gas-fired generation will be stable at the level of 2023 in both 2024 and 2025 – in other words, gas-to-power demand remains strong, but there is no further demand growth. If the conclusion is that gas demand from the electricity sector has peaked as the rapid expansion of renewables makes up for coal’s decline, the US gas market’s dependence on the international LNG market becomes even stronger.

Global LNG – looming glut?

Most LNG companies see global LNG demand rising significantly. Shell, for example, sees an increase of more than 50% by 2040 from 404mn tonnes in 2023. The primary drivers are industrial coal-to-gas switching in China and South Asia and increased LNG use in south-east Asia.

However, new capacity additions are already close to meeting this level of anticipated new demand. Some 193mn t/yr of new supply capacity are under construction, according to Global Energy Monitor’s LNG infrastructure tracker, with a huge pipeline of potential projects under development.

On the import side, there are 203mn t/yr of new capacity under construction. That new liquefaction capacity already closely matches new regasification capacity is one of the points made by the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEFFA), which argues that lacklustre demand and the wave of new production capacity will create a glut of LNG within two years.

However, import facilities on average have a much lower utilisation rate than liquefaction plants. At the end of 2022, regasification capacity worldwide was more than twice production capacity. Regas plants can also operate substantially above nameplate capacity. There is thus more than ample regasification capacity to absorb the increase in LNG supply, if demand increases in response to lower prices.

The key question is whether there is sufficient spare capacity in countries willing to take more LNG. In China, which can be expected to increase LNG use as a result of the signing of multiple new long-term contracts, the large-scale entry of non-national oil companies into the market and lower prices, regasification capacity utilisation was only 66% in 2022.

The country added substantial new regasification capacity in 2023 and continues to do so, so there is substantial scope for increased demand from the world’s largest and still heavily coal dependent LNG importer.

Demand in major mature LNG markets such as Japan, South Korea and Europe is less certain, owing to, in Japan, the return of nuclear power, and in all three increased construction of renewable energy capacity and energy transition goals designed to limit and reduce fossil fuel use. There are also significant financial, political and infrastructural challenges downstream, which may limit the growth of LNG demand in developing countries.

As a result, and although the future is always uncertain, the US gas sector’s growing dependence on international LNG could see periods in which clearing its gas inventories becomes very difficult.