Mexico: a new frontier for North American LNG [Gas in Transition]

Mexico looks set to become a considerable LNG exporter over the next few years. The likelihood of planned projects being developed has increased as a result of the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the associated decline in Russian gas exports to European markets. At the same time, US LNG developers have notably been unable to secure access to their own west coast.

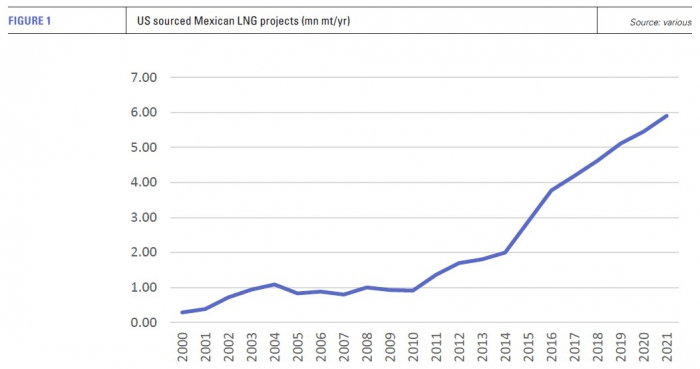

Much of the new capacity is to be developed by companies based in the US and will be fed by US gas, building on North America’s growing strength as a source of global gas supply (see figure 1). Obstacles remain in the form of limited transmission capacity and the need to continue supplying gas to Mexican industrial and power sector consumers, but a string of new projects looks more than likely to be completed.

Significantly, after some prevarications, state support for more rapid LNG development now appears to have firmed. Mexican president Andrés Manuel López Obrador publicly backed the Mexico Pacific Limited (MPL) project in August, while Mexico’s state power utility Comisión Federal de Electricidad (CFE) is involved in four of the country’s projects in different ways: Energía Costa Azul, Vista Pacifico, Salina Cruz and Altamira. The jobs, investment and export revenue that the projects will bring make effectively hosting outsourced US LNG capacity attractive.

Project pipeline grows

The biggest planned project is the Puerto Libertad LNG project, with capacity of 14.1mn mt/yr in Phase 1, with scope to double this when required. In July, operator MPL, which is based in Texas, signed a sales and purchase agreement with Shell to supply 2.6mn mt/yr from the first two trains. The LNG will be bought free on-board over 20 years, hopefully starting in 2026.

MPL President and CEO Douglas Shanda said of the Shell contract in July: “Their recognition of the advantages our location offers, including access to low cost Permian gas, avoidance of the Panama Canal to ensure a shorter shipping distance to Asia, and lower landed pricing, demonstrates the value of West Coast North American LNG.”

Meanwhile, CFE is directly developing two projects: its own 3mn mt/yr Salina Cruz LNG plant in Oaxaca state and the 4mn mt/yr Vista Pacifico scheme, partnering with California-based Sempra Energy.

Meanwhile, CFE is directly developing two projects: its own 3mn mt/yr Salina Cruz LNG plant in Oaxaca state and the 4mn mt/yr Vista Pacifico scheme, partnering with California-based Sempra Energy.

Salina Cruz will require the construction of the trans-isthmus Jáltipan-Salina Cruz pipeline and TC Energy’s Southeast Gateway subsea pipeline. Allseas announced in September that it had won a contract with TC Energy to install the 700 km offshore part of the pipeline, which is expected to be in operation by mid-2025. Germany’s Europipe will supply the pipe for the project.

Sempra also plans to develop the Energia Costa Azul (ECA) project in Baja California, with 3.3mn mt/yr in Phase 1 rising to 12.4mn mt/yr. It is particularly well placed given that it is located very close to the US border, next to an existing LNG import terminal, easing the permitting process.

Sempra owns the Rosarito pipeline that already runs across the US border to the site and which has sufficient capacity to supply Phase 1, which could be completed as early as 2024. Sempra has already secured supply agreements with US gas producers.

Another US firm, New Fortress Energy, is behind the Altamira LNG scheme, which will host 4.2mn mt/yr capacity. In addition, LNG Alliance of Singapore plans to build the Amigo LNG project with 3.6mn mt/yr in a first phase, with the prospect of doubling capacity later. LNG Alliance says the project will use existing gas pipeline infrastructure, but also require an extension of the Puerto Libertad-Guaymas pipeline.

Altamira LNG will be developed in the port of the same name on the Gulf coast using gas produced in Texas. CFE will supply the gas from the Texas-Tuxpan subsea pipeline, which has 80% spare capacity at present, to three 1.4mn mt/yr floating LNG units. It will also take 10% of production from the first and second trains, rising to 20% on the third.

The MPL and LNG Alliance projects are both on the Sonora coast opposite Baja California and are banking on feedstock being supplied by Sempra’s existing pipeline, but its existing transmission capacity of 770mn ft3/d would be insufficient to supply both projects. Both are due to take final investment decisions this year, but one may be forced to find gas from another source.

Why Mexico?

Given that these projects will be supplied with US feedstock, all this raises the question of why they will be built in Mexico rather than in the US. The main explanations seem to relate to the availability of suitable sites and potentially less challenging permitting processes. Many export projects have already been developed in the US in recent years, so a large proportion of the most suitable sites have already been occupied. None have been built on the US’ west coast, despite attempts.

In some cases, the transmission distances are hardly longer to proposed Mexican sites than to potential US locations given their proximity to the US border. There are likely to be some savings associated with developing projects in Mexico rather than the US, including labour costs. The US has long outsourced a large proportion of its manufacturing capacity across the Mexican border, so this latest trend is merely an extension of existing strategies.

Mexico also benefits from its geography. With both Atlantic and Pacific coastlines, it can supply Asian and European markets, despite not being particularly close to either. This allows producers to avoid the time and cost of transiting the Panama Canal. Mexican Pacific coast producers would save at least a week’s sailing time for volumes heading to the major LNG markets of Asia, in comparison with projects based on the US Gulf of Mexico.

Finally, private sector developers, the Mexican government and CFE now all appear to be working together to try to fast track projects to supply both the Pacific and Atlantic Basin LNG markets.

Transmission challenges

More pipeline import capacity from the US will be required, if all the planned liquefaction schemes are to be developed, while individual projects will require new transmission capacity within Mexico itself.

Mexico currently has the capacity to import 12bn ft3/d from the US, but imported an average of just 5.9bn ft3/d in 2021, according to US Energy Administration Information data. Given that 1mn mt of LNG requires about 48.7bn ft3 of natural gas feedstock, this surplus of 6.1bn ft3/d could in theory supply about 46mn mt/yr of LNG production. The current project pipeline suggests 32.2mn mt/yr of LNG capacity, potentially rising to 59mn mt/yr in later phases.

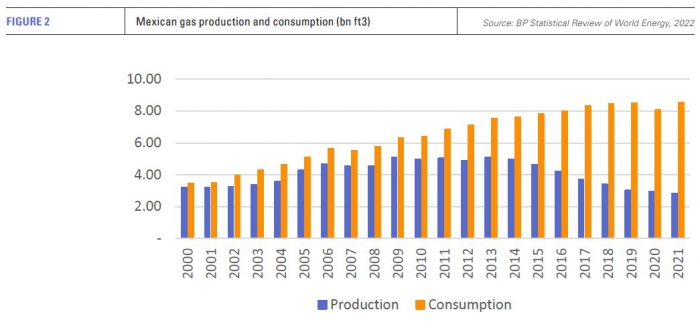

However, Mexican domestic gas production is falling and consumption is rising (see figure 2), while the spare transmission capacity is not always in areas where potential LNG producers could use it. Most existing pipeline capacity is designed to transport gas from the border to major urban centres, power plants and other industrial centres in Mexico rather than to the country’s coasts.

Progress is being made on the construction of new transmission capacity. In August, Canadian firm TC Energy signed an agreement with CFE to build a $4.5bn gas pipeline to connect the port of Tuxpan with Coatzacoalcos, plus the ports of Veracruz and Dos Bocas.

Developing the required transmission capacity is not always merely a matter of securing financing and various local, regional and national permits. Securing the support of local people can often prove to be the biggest obstacle. For instance, Vista Pacifico, which would be located at Topolobampo in Sinaloa state on the Pacific Coast, is already connected to CFE pipelines via the Guaymas-El Oro line, which has sufficient capacity to supply 600mn ft3/d of gas from the US, but is currently not being used because of a local dispute.

The Yaqui ethnic group opposed the pipeline project and it has been reported that they damaged the pipeline once it had been built in 2017. Local courts imposed an injunction against its repair, but a resolution could now be in sight following years of negotiations. Sempra and CFE have agreed to reroute the 150 km section of line that runs over Yaqui territory. Prospective pipeline developers often have to secure the backing of several different indigenous groups before construction can begin.

The Yaqui ethnic group opposed the pipeline project and it has been reported that they damaged the pipeline once it had been built in 2017. Local courts imposed an injunction against its repair, but a resolution could now be in sight following years of negotiations. Sempra and CFE have agreed to reroute the 150 km section of line that runs over Yaqui territory. Prospective pipeline developers often have to secure the backing of several different indigenous groups before construction can begin.

Putting the required pipeline capacity in place to funnel US gas to Mexican export plants may not be straightforward, particularly in relation to later phases of the Mexican projects. In most cases, there is currently no spare capacity to supply later phases, so new cross-border pipelines are likely to be needed, in addition to extra capacity on existing lines.

Global LNG demand on the rise

Signing its deal with MPL, Steve Hill, Executive Vice President of Energy Marketing at Shell said that global demand for LNG would continue to rise on the grounds of energy security. Bar a profound change of policy and probably also leadership in Moscow, Russian gas is likely to continue being displaced by LNG in Europe and it will be very difficult for Russia to secure alternative export markets big enough to displace all the gas that it previously piped to European customers.

S&P Global, for example, forecasts that LNG consumption worldwide will increase by 161mn mt/yr to 713mn mt/yr between 2022 and 2027.

European customers look certain to be at the front of the queue for Mexican LNG, with the German government already keen to secure imports of Mexican gas at the new import terminal at Wilhelmshaven. However, the world’s biggest LNG markets in northeast Asia, which have limited imports this year as prices have risen, should also benefit substantially, particularly from Mexico’s proposed west coast LNG facilities.