Middle Eastern LNG demand in flux [Gas in Transition]

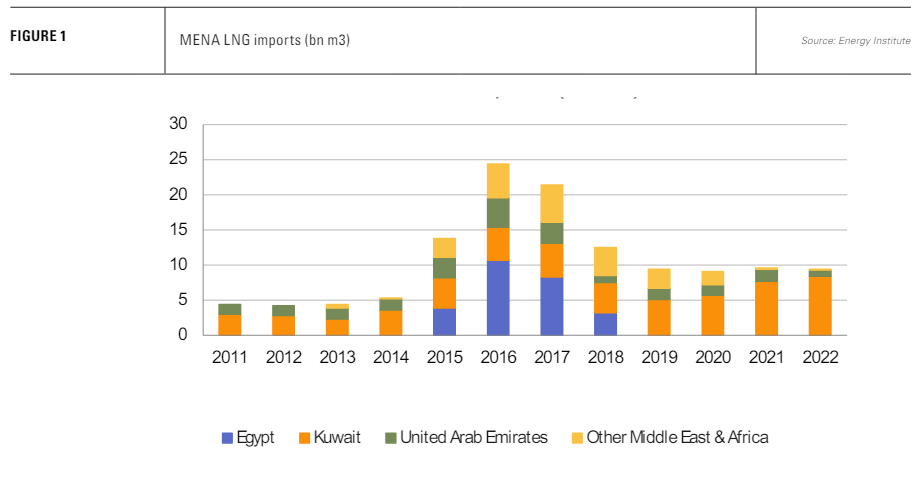

LNG imports into the gas-rich Middle East and Egypt’s connected gas system in North Africa have grown fast and faded almost as quickly as individual countries have discovered and developed more of their own resources. At a peak of 24.5bn m3 in 2016, the region looked like a major potential new market, but offshore Mediterranean gas put paid to continued growth (see figure 1).

By 2022, LNG imports had dropped back to just 9.4bn m3, almost all accounted for by Kuwait.

However, the regional gas balance is changing once again. Kuwait certainly has the below ground potential to replace all of its LNG imports with domestic production and has announced plans to do so. Questions remain over deliverability, timing and politics, but the country already last year appears to have capped to some degree the upward trend in its LNG volumes.

Meanwhile, moving in the opposite direction, Egypt looks likely to return to the LNG import market and is already bringing regasified LNG in via Jordan’s Aqaba import terminal under an agreement which runs until 2025.

Israel becomes a regional gas exporter

Israel’s change from LNG importer to gas pipeline exporter appears to be a more enduring feature of the Middle Eastern gas scene. Its exports are facilitated by pipelines to Jordan and Egypt in a region where regional pipelines are few and far between.

Hamas’s attack on the country did disrupt gas trade with the closure of the Tamar gas field platform and the cessation of Arish-Ashkelon pipeline flows from October 10 to November 14, but they have since resumed. Moreover, Israel was able to maintain flows from the larger Leviathan field through Jordan and into Egypt via the northerly Israel-Jordan pipeline and Arab Gas Pipeline.

In fact, Israeli gas exports to Egypt and Jordan were up by about a quarter in 2023 year on year with about 2.7bn m3 going to Jordan and 8.6bn m3 to Egypt.

Development of the Tamar field (2013) and Leviathan (2019) have been backed by the Karish field, which came onstream in 2022, and a decision in February to expand Tamar production from just over 10 bn m3/yr to 16.5bn m3 by 2025. Twelve offshore licenses were also awarded at the end of October to two separate consortiums.

Israeli gas flows to Egypt have been vital in maintaining the latter’s LNG exports and bolstering the country’s gas balance as output from the giant Zohr field has declined. It has also limited Jordan’s LNG requirements.

Egyptian gas output and demand

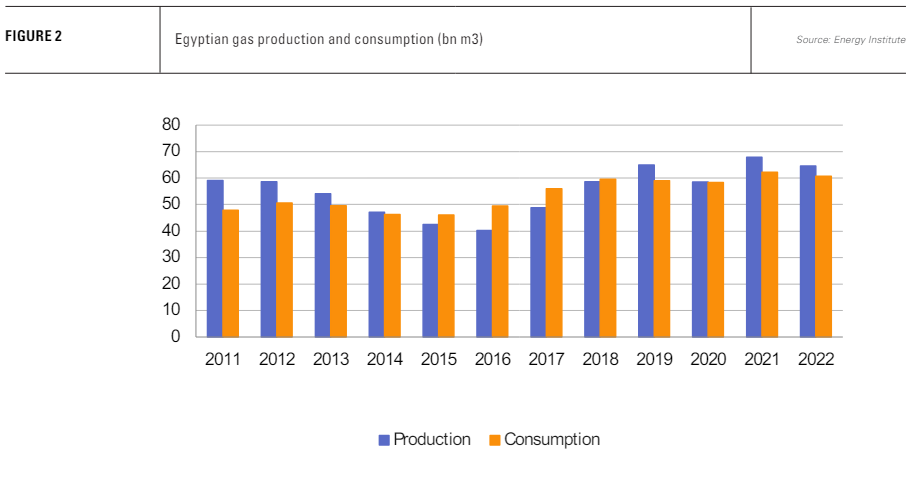

Egyptian gas production has seen something of a roller coaster ride over the last decade, slumping to 46bn m3 in 2015 before staging a rapid recovery as the government paid off its debts to gas producers and incentivised production by improving domestic market returns (see figure 2). By 2021, production had hit 62.2bn m3, owing to the fast-track development of a number of major fields, including the offshore Zohr field.

The rapid upturn, supported by imports of Israeli gas, allowed a resumption of and then increase in LNG exports.

However, gas production fell from its 2021 peak to 64.5bn m3 in 2022 and 59.3bn m3 in 2023, leading to a sudden drop in LNG exports to 4.5mn m3 last year, half the level of 2022. These have been sustained by a tripartite agreement between Israel, Egypt and the EU to allow Israeli gas imports to be used for LNG production destined for Europe, and by Cairo rationing domestic gas use to maintain exports in order to support the state’s foreign currency earnings.

Nonetheless, according to data from the Joint Organisations Data Initiative (JODI), LNG exports fell to zero from May to September last year, the period of highest domestic gas demand, before resuming at reduced levels in the remainder of the year, compared with the start of 2023.

A drop in production from the Zohr field, attributed to high rates of water infiltration, appears to lie at the heart of the decline, although commentators have also highlighted rapid depletion rates of 10-15% on other fields and a relatively small pipeline of new projects. Rating’s agency Fitch, for example, predicted in July last year that Egyptian gas production would decline steadily to 51bn m3/yr in 2032.

This outlook was balanced, however, by a strong exploration schedule and sustained interest in the Egyptian upstream by oil majors such as Chevron, BP and Eni, which developed Zohr.

On the consumption side, the Egyptian economy appears able to consume as much gas as is provided. Demand rose to a peak of 62.2bn m3 in 2021 and the subsequent drop reflects gas rationing and supply constraints rather than a lack of demand.

Although expansion of Tamar should allow an increase in Israeli gas exports, Cairo is moving to secure more LNG as well. The disruption to gas flows caused by Hamas’s attack on Israel may have been relatively minor but it and the subsequent regional tensions highlight the vulnerabilities of trans-national gas flows in the volatile Middle East.

In addition to securing cargoes for receipt in Jordan’s Aqaba terminal, Cairo is reported to be preparing to install an FSRU once again at Ain Sukhna. However, finding an available FSRU may prove a challenge, owing to the surge in FSRU installations in Europe since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, which has left few available for service elsewhere.

Kuwaiti LNG demand stable as domestic production rises

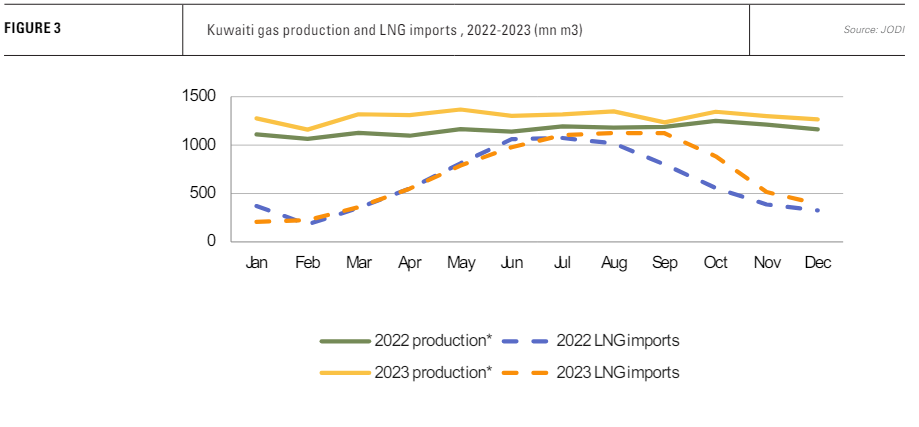

As Egypt hovers on the brink of a return to direct LNG imports, Kuwait, the bedrock of Middle Eastern LNG demand, appears to be having more success in raising its own domestic production, putting a cap on the growth of its LNG imports (see figure 3).

According to Energy Institute data, Kuwaiti gas production declined from a peak of 16.9bn m3 in 2018 to 12.1bn m3 in 2021, in part because of its dependence on associated gas production, which falls in periods when OPEC limits oil output. Gas production recovered in 2022 to 13.4bn m3. Over the same period LNG imports trended steadily higher from 4.3bn m3 in 2018 to 8.4bn m3 in 2022.

JODI data, which does not correlate directly with the Energy Institute’s, puts observed gross inland deliveries of gas in Kuwait at 13.9bn m3 in 2022, rising to 15.5bn m3 in 2023. At the same time, LNG imports increased only marginally from 7.5bn m3 to 8.2bn m3.

Increased domestic supply is in line with the Kuwait Petroleum Company’s (KPC) development of non-associated gas production, largely from its three Jurassic Production Facilities. Two more facilities are under active development.

However, the country has major plans to boost domestic gas production beyond its current needs, while at the same time increasing its renewable energy capacities to limit gas demand growth from the power sector. In October, the government announced a new strategy to boost oil production to 4mn b/d by 2035 from 2.9mn b/d currently. In addition, KPC’s 2040 strategy targets 20.7bn m3 of non-associated gas production by 2040.

With enhanced associated gas production from the increase in oil output, this, in combination with an increase in renewable energy, should cover Kuwait’s gas needs. On the demand side, however, electricity consumption continues to grow fast, while the need for desalination plants provides another energy hungry demand source. Subsidised sales of water and power mean Kuwait has one of the highest per capita electricity consumption rates worldwide, alongside a fast-growing population.

Target achievement in question

The big questions are whether Kuwait can achieve its targets in both the oil and gas sector and the renewable energy sphere. To date the record is not good.

At the end of 2023, Kuwait had only 114 MW of renewable energy capacity, registering no increase from 2022. Its 4-GW phase of the Shagaya solar project, announced a decade ago, has still not started construction and has been downsized to 2 GW. A tender was launched in January for 1.1 GW.

Part of the problem is that the only bodies mandated to construct power plants are the Ministry of Electricity, Water and Renewable Energy and the Kuwait Authority for Partnership Projects. Both are subject to political control and Kuwait’s political system remains gridlocked. Another dissolution of parliament in February suggests little imminent improvement on the political front.

Oil and gas production targets have also been repeatedly missed, reduced and pushed back. In addition, Kuwait is pinning a large part of its ambitions on the Dorra gas field which lies in a maritime area contested by Iran. Kuwait and Saudi Arabia claim that they jointly own the field. In March, Iran said that if Kuwait starts to extract oil and gas from the Arash-Dorra field, it will follow suit. The field was discovered in 1960, but has seen no production because of its disputed ownership.

Saudi Arabia and Kuwait are targeting the start of gas production from Dorra by 2029, but to push ahead with development would add another bone of contention to the region’s already tense politics.