MiQ: the case for voluntary action [Gas in Transition]

The US is set to tighten methane regulations governing the oil and gas sector over the coming years, after US president Joe Biden in June reversed a Trump-era loosening of the rules. But several market-based solutions have also emerged, aimed at helping gas companies address their emissions faster.

One such solution is MiQ, a non-profit initiative that was launched by the US RMI and Systemiq in December 2020. At its core, MiQ strives to give companies an incentive for making their gas cleaner, using what its developers hope will eventually become global standards for detecting, quantifying and eliminating methane emissions.

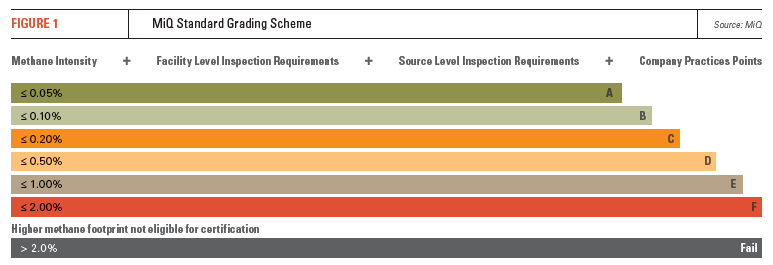

MiQ is still at the pilot stage. But it works by grading gas producers that sign up to the initiative based on their methane intensity, how frequently and effectively they inspect their facilities and the company practices they have introduced. Independent auditors are used to determine companies’ grades.

Producers’ gas is graded on an A to F basis. To score A, it must have a methane intensity of no greater than 0.05%. For B it must be no more than 0.10%, C 0.20%, D 0.50%, E 1.00% and F 2.00%. There are rules for how producers must detect and quantify their emissions. They must undertake leak detection and repair (LDAR) work at their facilities at least once a year to be graded at all, for example. To achieve a C or higher, they need to reconcile their bottom-up, ground-level data with top-down data provided by satellites and airplanes. And to score B and A, LDAR inspections need to take place on a semi-annually and quarterly basis respectively.

A number of US producers have announced plans to get their certified under the MiQ standard. Most recently, ExxonMobil said on September 7 it would seek MiQ certification for around 200mn ft3/day of gas supply from Poker Lake in New Mexico. The US major will consider certifying gas from other fields in the Permian basin and other shale production areas, including Appalachia and Haynesville. Other operators to sign up to MiQ include Chesapeake Energy, EQT and Northeast Natural Energy.

The first audits are expected to be completed in the fourth quarter, after which certificates will be issued.

Carrot and stick

The US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) will propose new methane regulations for the oil and gas sector this month, with the new rules expected to be tougher than those that were imposed by the Obama administration and subsequently rolled back by Trump.

MiQ’s developers welcome the incoming regulation, but still see voluntary action as playing a crucial role in addressing emissions.

“While we fully embrace regulation and we find that there’s some excellent examples of how it can be implemented, this voluntary action is something we can do today,” Lara Owens, project manager at MiQ, explains to NGW in an interview. “We can put into place robust transparent standards that are able to influence markets very quickly.”

MiQ and other voluntary initiatives can also help guide future regulations by effectively “road-testing” the implementation, she says.

The idea behind MiQ is that companies with higher grades will be able to sell their certified gas at premium, and potentially receive a bump in the share price from having better environmental, social and governance (ESG) score. On the other hand, ungraded companies may have to sell their product at a discount, and as MiQ becomes more widely adopted, they could even be forced out of the market if they do not improve.

Owens says it is difficult to determine how quickly a premium for certified gas would emerge.

Owens says it is difficult to determine how quickly a premium for certified gas would emerge.

“This is a very new market, but we know there is appetite for it,” she said.

For voluntary initiatives like MiQ to work, they need to be transparent, credible and consistent, with robust third-party auditing, Owens says. A global standard is needed rather than numerous initiatives using different standards and practices.

“The investors, the insurance companies, the buyers – they want to have clear metrics for understanding the merits of the voluntary actions,” Owens says. “That’s why having this global standard is a really critical element.”

MiQ has various rules in place to ensure that the third-party assessment process is robust.

“No companies can be a third-party assessor if they have conflicted interests,” Owens explains. “They can’t be involved in the MiQ standard’s development, the solutions and emissions counting, the detection, they can’t be consulting on behalf of the company. They need to be oil and gas experts.”

So far five auditors have been accredited.

MiQ’s developers are working on expanding the standard to midstream operations, such as LNG delivery and pipelines, as part of a lifecycle assessment process. This would allow gas buyers in Europe, for example, to know how much methane was emitted from the production and transportation of the US gas they buy, Owens says, adding that the hope was that operators start piloting this midstream standard next year.

While so far only four companies have publicly announced plans to certify their gas under the MiQ standard, talks are underway with dozens more in the US, Canada and elsewhere in the world.

“There has been a lot of early interest in southeast Asia,” Owens says.