Mixed messages for oil and gas [Gas in Transition]

Oil and gas companies have been under immense pressure from the US and the EU to stop investing in new fields and support the transition to cleaner fuels. They have responded to this, with current investments in exploration and production down to about 50% of the levels during the heydays of the sector, in 2013/2014. In fact, oil major capital spending plans are still below pre-pandemic levels, with no plans to raise them in the medium-term. The outcome is reduced reserves, tight spare capacity and inability to respond to increased demand._f600x198_1670840239.jpg)

This is now coming home to roost. At a time when global oil and gas demand has been increasing as the global economy has been coming out of the pandemic, supply has been unable to respond at the same pace, with the inevitability that market forces have been driving prices up.

This has been exacerbated by the Russia-Ukraine war. Sanctions on Russia, not only have led to major reductions in Russian oil and gas supplies to Europe, but have also taken substantial quantities of Russian oil and gas out of global markets, making supply even tighter and inevitably pushing prices further up.

Policy paradox

In the middle of a global energy crisis, a policy paradox is emerging, where western governments call for OPEC and other oil and gas producers to raise output while also saying they want to transition away from fossil fuels and restrict investment in more supply.

Haitham Al Ghais, OPEC’s secretary-general, said recently that “mixed-messages” are holding back energy investments “sowing seeds for future energy crises – not just one, but multiple.” He pointed-out that with "average annual decline rates around 4-5%, you are talking about needing to add 5mn barrels/day every year just to maintain today's global production, let alone meet future demand." He stressed that "The discourse needs to be inclusive, welcoming all voices to the table. We cannot return to a world that is limited by the question: are you for or against fossil fuels? It cannot be just one or the other. This limits the options available to help the world meet the interwoven challenges of energy affordability and security that have emerged starkly in the past year, while also reducing greenhouse gas emissions."

The paradox in the US is stark. American Petroleum Institute CEO Mike Sommers criticised the Biden administration for sending "mixed messages." He said “It's really unbelievable where you have John Kerry on one side saying that this industry needs to end by 2030. And then you have Jennifer Granholm and the president saying that we need to produce more. Which one is it?”

Mike Wirth, Chevron’s CEO, took a similar view last month. He said a premature effort to transition from fossil fuels has resulted in “unintended consequences”, including energy supply insecurity. With variable, intermittent, renewables in mind, he warned that Western governments have made a global oil and gas crunch worse by doubling down on climate policies that will make energy markets “more volatile, more unpredictable, more chaotic.”

The International Energy Agency (IEA) showed in its latest World Energy Outlook 2022 that, based on its Stated Policies Scenario, even though oil and gas demand may stop increasing beyond the mid-2030s, the world will still need oil and gas at quantities similar to today even by 2050.

In the US, president Biden has been threatening oil majors with windfall tax unless they step up investment to tame high fuel prices. Given that he promised to transition the US off fossil fuels, this is an inconsistent argument. But there are many reasons why this will not happen: a volatile market and mixed-messages about the future of fossil fuel demand mean that the oil majors are sticking with their existing spending plans, limiting new production.

The world needs more energy

Expanding populations and growing economies mean the world will need more energy. That is what BP’s Energy Outlook 2022 shows (see figure 1), based on the New Momentum scenario, “designed to capture the broad trajectory along which the global energy system is currently progressing. This places weight both on the marked increase in global ambition for decarbonisation seen in recent years and the likelihood that those aims and ambitions will be achieved, and on the manner and speed of progress seen over the recent past.”

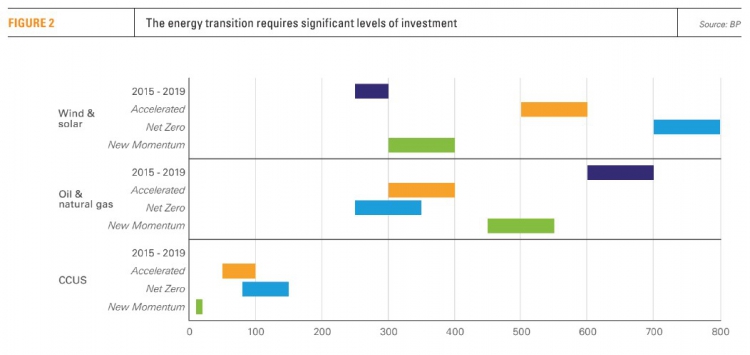

BP also considers two other scenarios, Accelerated and Net-Zero. But these are based on trajectories designed to broadly meet Paris Agreement targets. This requires new clean energy technology and dealing with long-term intermittency – still challenging. These require substantial levels of investment, two to three times higher than so far (see figure 2).

Even though oil demand drops by 20% by 2050, the decline is slow and the world will require something like 80mn bls/d even by 2050 under the New Momentum scenario. Natural gas demand is expected to carry on increasing, by as much as 25% by 2050.

BP also concludes that “although the demand for oil and gas falls in all three scenarios, natural decline in existing production implies that continuing investment in new upstream oil and gas is required in all three scenarios, including Net-Zero. In fact, current upstream investments are at about the levels corresponding to the Accelerated and Net-Zero scenarios and well below the level required by New Momentum. It is then not surprising that oil and gas supply is tight, not meeting the pace of increase in demand, supporting the arguments being made by Al Ghais.

During energy transition, and until renewables reach the levels required by the Accelerated and Net-Zero scenarios – and prolonged intermittency is dealt with – oil and gas production will need to be maintained if the world is to avoid frequent energy crises.

We all want to arrest climate change. The global goal remains to switch to green energy and eliminate carbon emissions, as well as arrest erosion of natural carbon sequestration. But until we get there, the world will still need secure and affordable supplies of oil and gas, and for a long time to come. COP27 confirmed that, with the majority of participating states going for energy security, by not supporting oil and gas phase-down.

Unless we face this reality, the world, and especially Europe, will sleep-walk into the next energy crisis later this decade, as the need for gas to make up for non-performing renewables becomes apparent. Without new production, gas supply will be a problem,

Reality is that, so far, the big winner from this crisis is coal – up by 6% in 2021 and more this year - the world needs to get out of coal and replace it with renewables supported by natural gas during transition.

Europe’s conundrum

The IEA is warning that “Europe is set to face an even sterner challenge next winter. This is why governments need to be taking immediate action” and recommends speeding-up improvements in energy efficiency and accelerating deployment of renewables. But if winter turns-out to be colder-than-normal and calm, as some forecasts show, such measures may not be enough. Lower temperatures will lead to increased gas consumption and calm weather will lead to reduced renewable energy production, including reduced hydro, putting even more demands on gas consumption. Renewables intermittency is still a challenge and, until the problem of long-term electricity storage is resolved, it will remain a challenge. Uninterrupted, secure and reliable electricity supplies can be ensured only with back-up from fossil fuels, preferably gas.

Unfortunately, the inability of renewables to step up and provide reliable and continuous energy, accompanied by the tightness in gas supplies, has led to a resurgence in coal consumption globally, including Europe.

This has given a boost to green hydrogen. It is attracting considerable investment but has a long-way to go before it is produced in significant quantities at competitive prices. In any case, using green hydrogen, produced with renewable electricity, for power generation is highly inefficient.

However, if anything, Europe is speeding-up its exit from fossil fuels, as evidenced by its REPowerEU strategy and recent statements from the European Commission.

But there are signs that some re-thinking is taking place. Germany is close to breaking its gas funds pledge made at COP26. Its new position is “we reserve the right to do what is necessary to make gas available as an energy source, stressing at all times its transitional nature.” Will the EU follow suit before the next crisis and accept that natural gas will be needed well into the future?