Myanmar’s Chinese gamble [NGW Magazine]

When China’s president, Xi Jinping, kicked off his 2020 foreign travel program in January, his first stop was Myanmar – even while Covid-19 had a firm grip on his own country.

Asia’s superpower cares so much about one of the poorest countries in the world because it is keeping a close watch on the security of its gas imports. And its pipeline connections with Myanmar are rising to the top of its list.

Gas shortages on China’s mainland are severe, even for an economy where growth has stalled. Analysis by Bloomberg Intelligence found that foreign suppliers could expect to meet three quarters of this year’s demand. That is a significant rise from 57% in 2017. The shift from coal to cleaner-burning fuels is one key driver. In LNG imports China now exceeds all other individual countries.

Compared with other key supplies, Myanmar’s gas is a gift: cheap and reliable. Gas from the Middle East by contrast has to cross vast oceans including the Malacca Straits with pirates adding to the insurance bill; and on top of that come expensive LNG carriers. These imports are creating serious economic burdens, while the lower prices that come from pipeline deliveries of natural gas will aid the country’s post-pandemic economic recovery.

Myanmar’s Zawtika and Shwe fields are where the gas for China now resides. Myanmar’s energy ministry once posted an announcement: “Most of the gas produced within Myanmar… is exported to China and Thailand, so the domestic gas demand cannot be sufficiently satisfied.”

This is why Chinese interest in the town of Kyaukpyu is so critical: it is the chosen site of a new port to connect with two pipelines transporting gas and oil to China. Kyaukpyu is a relatively insignificant coastal town along the Bay of Bengal in Myanmar’s western-most state of Rakhine.

Despite the global recession brought about by the pandemic, and despite Myanmar’s relative isolation from the world, the national government is still anxious to construct this mega-project: a $7.3bn deep-water port and $2.7bn industrial area. The latter will be in a special economic zone (SEZ) at Kyaukpyu, along the coast of the Bay of Bengal. Agreements to undertake this mega-project have been signed with Chinese state-owned firms – and these contracts have set off alarm bells around the world.

China has remained committed to the Kyaukpyu projects primarily because the town is the terminus of two assets: a $1.5bn oil pipeline and a parallel natural gas pipeline running to Kunming, capital of southwestern China’s Yunnan Province.

Unlike any of the other major infrastructure projects related to Kyaukpyu, construction work on the pipelines has moved forward despite significant local opposition. They were built between 2010 and early 2015 by China National Petroleum Corporation and Myanmar Oil and Gas Enterprise – both state-owned firms – with CNPC as the majority stakeholder. The gas pipeline became operational in 2013 and is capable of exporting 12bn m³/yr to China.

After a two-year delay, the oil pipeline started up in April 2017. Some reports indicate that it can carry 22mn barrels/yr, which amounts to about 6% of China’s oil imports. This pipeline project is part of China’s strategic Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) to reduce its reliance on imports through the Strait of Malacca. Pirates apart, China wants to prevent an adversary such as the US from closing the strait.

The threat to Myanmar

Despite fears that this new project could eventually be used to enable and facilitate Chinese military access, project advocates say that there are political and legal restrictions in place in Myanmar which make this unlikely. The project is focused on helping China avoid the vulnerable Strait of Malacca and on aiding the development of Myanmar’s southwestern hinterland.

Like many major projects in China’s trillion-dollar BRI, there are well-founded fears that the project could grant China a high degree of financial leverage over Myanmar. This is especially worrying for critics of the project if the national government, based in Naypyidaw, is forced to turn to Chinese loans in order to fund its share of the port and SEZ. When combined, these could amount to 5% of national GDP.

In 2016, subsidiaries of China’s Citic Group, including China Harbor Engineering Company, won contracts for two major projects in Kyaukpyu – the dredging of a deep-sea port and the creation of an industrial area in an SEZ. The port project is valued at $7.3bn and the SEZ at $2.7bn. Under the terms of the deal, Citic will build and then run the project for 50 years with a potential extension of another 25 years.

Negotiations on Kyaukpyu however predate the BRI: Citic signed initial memorandums of understanding (MOUs) for the harbour project and a railway connecting the SEZ to southern China in 2009. However, they languished amid political sensitivities in Myanmar surrounding Chinese investments following the 2011 suspension of the Myitsone dam project and violent protests starting in 2012 over the Letpadaung copper mine. The railway MOU was canceled in 2014 while the port and SEZ industrial area projects are moving forward, but slowly and with considerable pushback within Myanmar. Only in October 2017 did the two sides reach an agreement on ownership of the port project after Citic agreed to drop its stake from 85% to 70%. Ownership stakes in the SEZ have yet to be finalised.

Pipeline short-cut

Building a deep-sea port at Kyaukpyu makes considerable economic and strategic sense for China in its drive to develop its inland provinces. Shipping goods from Europe, the Middle East, Africa, and India to Kyaukpyu and then overland to Yunnan could save thousands of miles. It would be far more efficient than sailing all the way through the Strait of Malacca and the South China Sea to ports along China’s southern and eastern coasts, and then travelling overland to China’s western provinces.

Unsurprisingly, in December 2017, Myanmar’s leader Aung San Suu Kyi and Xi agreed in Beijing to establish a new China-Myanmar Economic Corridor connecting Kyaukpyu and Kunming. No details were released, but the project would likely include construction of a road and perhaps the restart of the suspended rail project. Mandalay, Myanmar’s second-largest city and the traditional hub for trade with southern China, would serve as a staging-post along this new economic corridor. Ultimately it seems Chinese planners envisage the Kyaukpyu - Kunming oil and gas pipelines as just the first step in a new trade route that could change the economics of China’s hinterland.

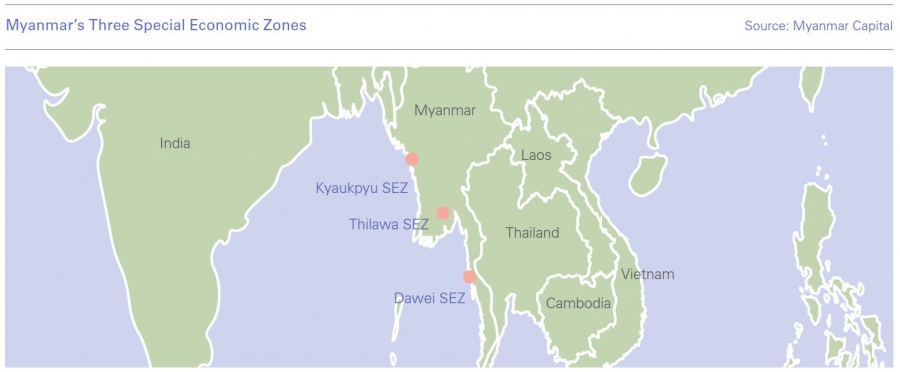

While the establishment of a deep-sea port at Kyaukpyu makes sense for China, any benefits for Myanmar will depend in large part on the success of the accompanying SEZ. Without successful industrial projects in the SEZ, Kyaukpyu could become little more than a waystation for goods headed to Yunnan. The former government of Myanmar under Thein Sein promoted three large SEZ projects to boost the country’s economy. Of these, the Japanese-led Thilawa SEZ just outside Yangon is the only one already up and running. Another, the joint Thai-Japanese Dawei project along the southern coast, has faced constant financial troubles but continues to move forward slowly. That puts Kyaukpyu third in a three-way race, and it is unclear whether the zone, with its late start and distance from Myanmar’s commercial and economic heart of Yangon, will be able to lure sufficient investment.

There are concerns among some in India and the West, as well as within Myanmar itself, that China could leverage the port at Kyaukpyu for military purposes, but such worries are premature at best. Myanmar’s leaders, both military and civilian, are famously jealous of the nation’s sovereignty and will not accept a permanent foreign military presence, whether from China or anywhere else. In fact, the country’s 2008 constitution expressly forbids the deployment of foreign troops on its soil.

That means that commercial investment in the port at Kyaukpyu is not likely to lead to a permanent Chinese presence such as in Djibouti or, reportedly, Gwadar, Pakistan. Chinese naval assets could certainly pay calls to the port from time to time, as they do at Colombo in Sri Lanka, which is also majority-owned by a Chinese company. But such port calls should not by themselves be cause for concern.

|

Slippery slope towards debt Critics fear that closer ties between Myanmar and China could put the smaller nation on a slippery slope by providing China a dangerous level of economic leverage over Myanmar owing to the accumulation of too much Chinese-funded debt. Chinese loans and large-scale investments have proven highly controversial in other regional states, such as the Maldives, where Beijing has been accused of using debt as a lever, forcing governments to make political and economic concessions that go against its national interest. Such fears are not unfounded. The Myanmar government’s 30% stake in the Kyaukpyu port amounts to $2.2bn. If it takes a 50% stake in the SEZ, that would bring its total responsibility for the projects to $3.5bn, or about 5% of GDP. As Yun Sun at the Stimson Center has pointed out, if the Myanmar government cannot handle that level of financing, it will likely turn to Chinese loans. Concerns about Chinese economic leverage help explain the continued local opposition to Kyaukpyu and the slow rate of progress. One of the driving factors behind Myanmar’s decision to move toward civilian government in 2010–2011 was a worry about overreliance on China amid continued Japanese and Western sanctions. For the time being, China remains a major but not overwhelming economic presence in the country. China has a major footprint in Myanmar, both in trade and investment, but so do other partners like Japan that provide Myanmar with a significant degree of manoeuvrability. That is not likely to change in the short term, though the potential debt burden from Kyaukpyu bears watching. Kyaukpyu is of considerable strategic and economic value for China as it seeks to speed development of Yunnan and its other inland provinces. That value is centered on the development of a deep-water port and the construction of accompanying road and rail links to supplement the pipelines already running to Kunming. Whether the project also boosts Myanmar’s economic growth depends upon the success of the accompanying SEZ, and the terms under which it takes shape. |