Natural Gas to Weather Growing Economic Headwinds [NGW Magazine]

The world’s two largest economies, the US and China, are engaged in a tit-for-tat trade war in which Washington has imposed tariffs on an estimated $250bn-worth of Chinese goods. A second round of US sanctions will be re-imposed on Iran by the US from November 5, while sanctions remain outstanding on various aspects of energy sector investment in Russia. Europe faces the uncertain prospect of leaving the European Union and the risk of doing so with no trade deal in place.

Against this backdrop, economic indicators suggest a slowdown in the momentum of global trade. The OECD’s Composite Leading Indicator, designed to signal turning points in the business cycle, has been trending down since November 2017. The reading for August was the lowest since August 2013. The WTO’s World Trade Indicator likewise points to a weakening economic outlook. China reported GDP growth of just 6.5% for the third quarter, the lowest level since first-quarter 2009, suggesting the trade war with the US is starting to bite.

At the same time, the oil price has been creeping steadily higher, nudging over $80/barrel, as producers struggle to make up for the huge drop over the last 18 months in Venezuelan output and the impending impact on Iranian crude exports of US sanctions. The oil price is essentially redistributive between net exporters and importers, but higher prices act as a consumption tax and push up transport costs.

All in, the outlook for global trade has taken a bleak turn.

Long-term forecasts

Slower growth today has a compound effect when expressed in long-term energy forecasts, which depend heavily on GDP growth to gauge expected future energy demand. Although GDP expectations reveal nothing about the composition of demand, they provide a guide to the overall size of the future pie. If that pie starts to look not so much smaller but less big than before it will affect energy sector investment decisions.

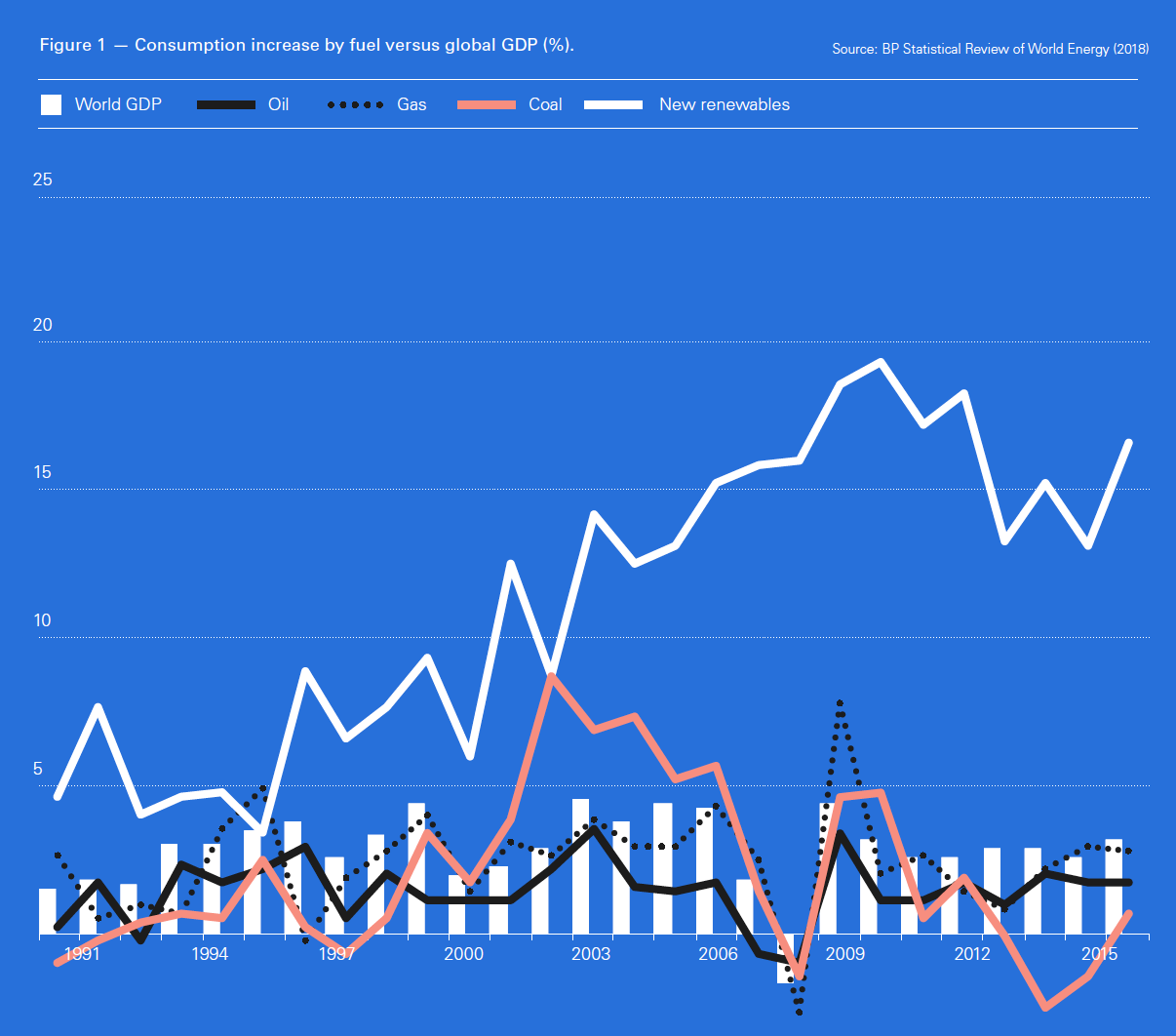

However, the composition of energy demand is also critically important, and more subject to change over the coming decades than in the past because of the technological responses to climate change. Driven by environmental imperatives, cleaner technologies continue to challenge the position of established energy commodities. While oil will bear the brunt of electric vehicles, gas has arguably already suffered in the power sector from renewables subsidies, followed by the rapid drop in wind and solar costs, which have seen it eased out of competitive tendering in warmer climes, for example in South America.

Paradise postponed

Within this context there will be some clear winners and losers, but although a Golden Age for gas has been called before, only to disappoint, the outlook for the fuel is undeniably bright.

Gas was supposed to be the perfect partner for variable renewables in the global effort to decarbonise, but in European power markets at least it has faced years of marginal profitability. It was supposed to rip market share from oil in marine transport, but the number of LNG-fuelled ships remains small, and gas in land transport, while growing, never seems to gain real traction.

Gas has never quite lived up to its potential in part because of the industry’s rose-tinted worldview. The industry pushed the message that gas was clean, secure and cheap, ignoring the fact that these attributes were relative rather than absolute. They depended and still do depend on the market context and the alternatives.

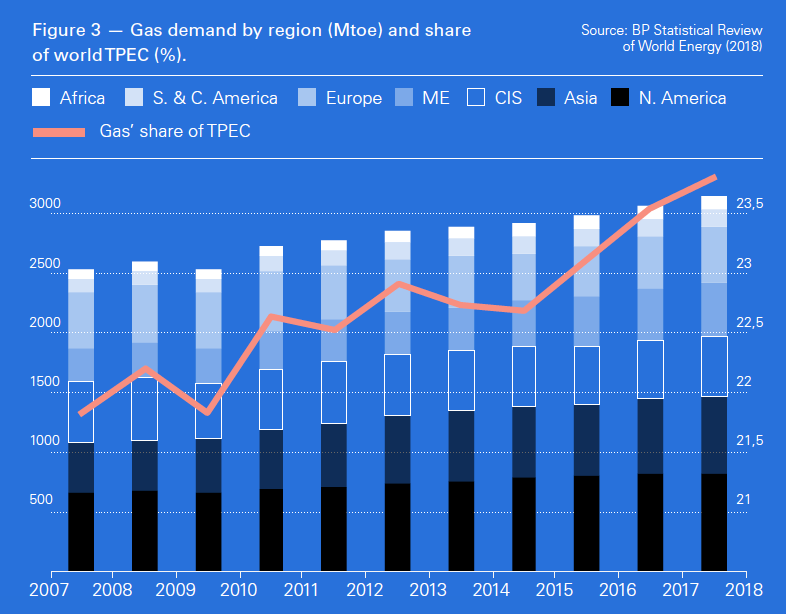

Yet even as global growth prospects soften, there are solid reasons to be optimistic for natural gas. This can be seen from the steadily rising proportion of world total primary energy consumption met by gas, which has risen from 21.9% in 2007 to 23.6% in 2017, despite the boom in renewables deployment over this period.

Regional diversity

Moreover, gas’ success stories are regionally diverse. US gas demand has seen an exceptional reversal since the global financial crisis. Having fallen between 2000-2009, it jumped 14% between 2010-2017. In addition to rising pipeline and LNG exports, in recent years, new power plant construction in the US has been almost equally divided between gas-fired generation and renewables.

In the US, nuclear projects, few and far between in any case, are financial disasters and the aging coal fleet appears beyond economic redemption in an era of climate change and abundant gas co-production on the back of the shale oil boom. Even with relatively low levels of power demand growth, and despite competition from wind and solar, gas is growing above trend in the North American market.

China too is onboard but for different reasons. Its program last year to switch heating in northern provinces from coal to gas again represents long-term structural change in demand, one which proved a key factor underpinning LNG prices last winter in what otherwise appeared a market slipping into over-supply. China’s drive to clean up its smog-ridden cities will continue to benefit gas over coal in heating for the long term even as overall GDP growth slows.

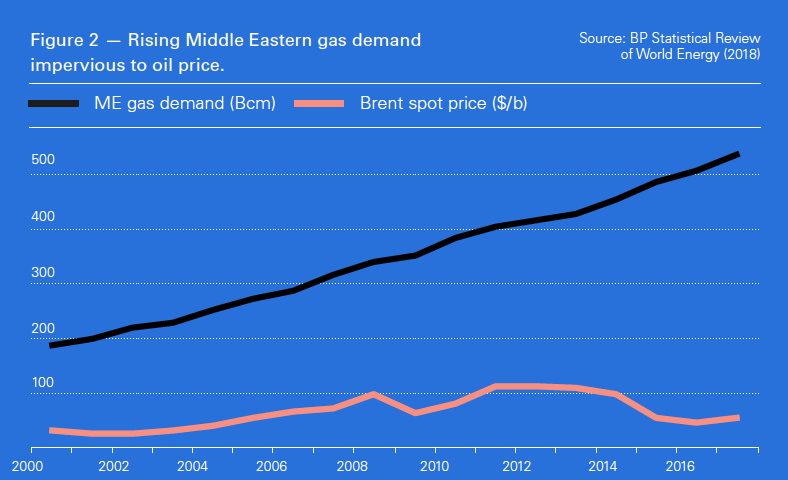

Then there is the Middle East where gas demand has been on a steep upward curve for the last 20 years, one seemingly impervious to the oil price, which plays a key role in determining the region’s spending power. Demand has been driven by youthful populations, and the need to generate power for air conditioning and desalination. Middle Eastern refiners and petrochemicals producers have consistently substituted gas for oil in order to maximise export revenues. Here gas has benefited at the expense of oil rather than coal.

New markets

However, it is the new market potential for gas that should give most succour to the industry, not just geographically but across demand sectors.

The number of LNG-importing countries continues to edge up year on year, the populous nations of Pakistan and Bangladesh being two of the most recent arrivals. Gas is the quickest and easiest means of reducing carbon emissions for heat and power where coal and oil are the primary fuels in use.

Decarbonising heat is arguably the next great environmental challenge and renewables do not offer the same possibilities here that they do in power generation; gas for coal or gas for oil switching is the low hanging fruit.

Gas will also continue to pick up market share in transport. This is likely to be modest, but electric vehicles do not pose the same kind of exogenous demand threat to gas that they do to oil. For oil, transport is bedrock demand at risk, for gas it remains a market opportunity.

The rise in global gas consumption last year may have appeared unexciting at just 2.7%, particularly when set against 17% growth for renewables, but it still compared well with oil (1.8%) and coal (0.7%).

For the long-term, even as the global economy’s prospects darken, and the future energy pie starts to shrink, gas demand will be underpinned by the structural changes in China and the US, the opening up of new markets geographically and across demand sectors, as well as gas’ position as the cleanest of the fossil fuels in the challenge to limit emissions from heat generation.