New doubts over fate of Mozambique LNG [Gas in Transition]

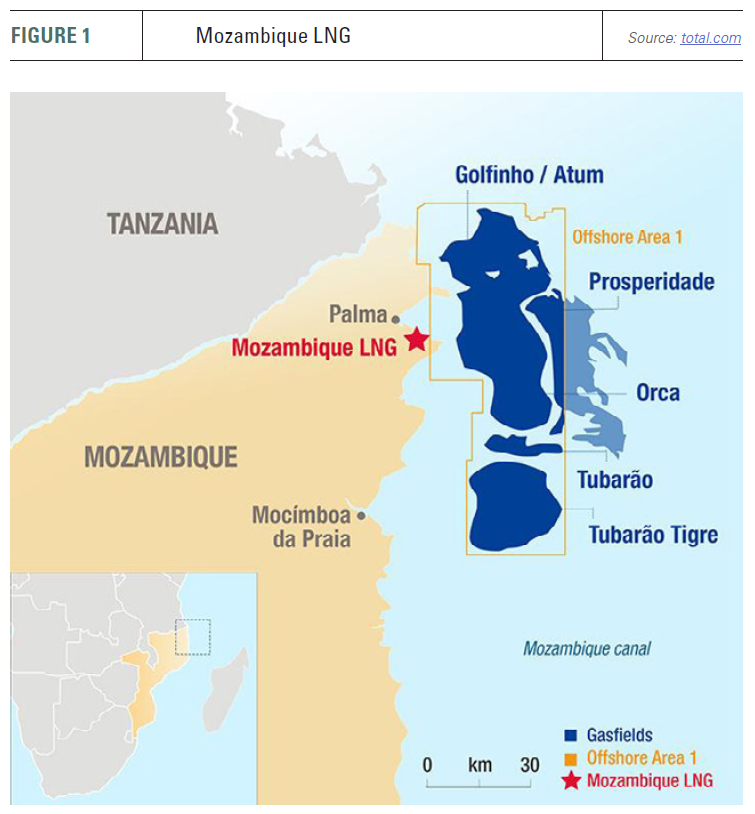

The fate of Mozambique LNG is in more doubt than ever before, following the latest spate of attacks by the Islamist insurgency in Mozambique’s Cabo Delgado Province, where the Total-led project is located.

Total had been preparing to restart construction work at the Mozambique LNG site as recently as March 24, having withdrawn most of its workforce from the site in January after the insurgents carried out an attack nearby. The French company had asked the Mozambican government for additional security measures, and these were implemented, which it expected to allow it to return staff to the site.

However, this plan was scuppered within days by yet another attack. On March 27, Total said it was postponing the restart of construction, instead opting to evacuate its remaining workers at the site as insurgents attacked the nearby town of Palma.

While Palma was subsequently retaken by the Mozambican government from the Islamic State-linked insurgents, at least 10,000 people were reported to have fled from the attack as of the first week of April, seeking refuge in the village of Quitunda, less than a kilometre from Total’s camp. The site is considered by displaced people to be safe as hundreds of government troops are stationed there in an effort to protect the Mozambique LNG project.

Implications

The escalating situation in Cabo Delgado does not bode well for Mozambique LNG or either of the other two liquefaction projects planned for the area – the Eni-led Coral South floating LNG (FLNG) development and ExxonMobil’s proposed Rovuma LNG terminal.

While the risk posed by the insurgency has been acknowledged in the past, it is only recently that the fighting has come close to Mozambique LNG’s site on the Afungi peninsula. Even now, opinion is mixed on whether Mozambique LNG and the other projects can end up being completely derailed or not.

On one hand, the developers of major oil and gas projects have become increasingly risk-averse, especially when faced with escalating costs and the delays behind them, while Mozambique’s government appears ill-equipped to contain the violence. On the other hand, Mozambique is counting on these LNG projects to provide a significant boost to its economy and could be inclined to devote significant resources to saving these investments. Meanwhile, both Eni and Total are further along in building their respective projects, while ExxonMobil has not even reached a final investment decision (FID) on Rovuma LNG, and could find it comparatively easier to pull out of the region at this point.

“What you see for the term of project development and major capital projects, in which LNG projects are included, is that the risk that's starting to limit project execution is moving away from technical and is moving more towards commercial and political,” Ackerman tells NGW. “The underestimation of commercial and political risk is what's biting Total and Exxon here.”

Indeed, Ackerman says he would go as far as excluding both Mozambique LNG and Rovuma LNG from global supply forecasts – or at least viewing them as much more long-term options.

“I think it's going to be so far the road that you're looking at a Gorgon timeframe. Gorgon was discovered in Western Australia in ‘84 and didn't get commercialised till the mid-2010s,” he notes. “That’s almost 30 plus years of development, for various reasons – some technical challenges, but a lot of them were commercial and a lot of them were political,” he continues.

Now, Ackerman expects to see similar setbacks for the Mozambique and Rovuma LNG projects in terms of timing. “I don't believe that in the near term, within the next 10 years, those projects will be on stream, the reason being the country cannot cope or control the political situation. It's too weak,” he says.

Others remain more optimistic over the resilience of the projects and their operators, though. Poten & Partners’ head of business intelligence, Jason Feer, tells NGW that while the scale of recent attacks in Cabo Delgado had surprised people and were a cause for concern, oil and gas companies have long worked in challenging environments, including conflict zones.

“I don't think this has really shaken anybody's faith in the project so far, but I think the investors obviously are going to want to see the government taking more steps, and I think those companies will be taking more steps to bolster security,” he said.

One major issue Feer pointed to is the impact the security situation in northern Mozambique could have on efforts to drive down project costs. And given the high levels of uncertainty around how the situation could evolve, this threatens to be a complex problem to solve.

Seeking solutions

The various companies involved in Mozambique’s nascent LNG scene are now faced with the considerable challenge of figuring out how best to proceed in the face of rising volatility on the ground.

Ackerman suggested that out of the three operators, Eni could be best-positioned with its Coral South FLNG project – in which ExxonMobil is also a partner – given that it will be located offshore.

“If they go back to the drawing board, maybe they should reconsider to 2.0-3.5mn-tonne Prelude-like FLNG facilities, and put them offshore, because that's not going to be any later to first LNG than what they're currently experiencing. And it has a higher chance of success if they keep it offshore,” he suggests, referring to the other operators.

This approach would have its own challenges, however. The Prelude FLNG project cited by Ackerman, offshore Australia, has struggled with technical problems. And Feer said that trying to replicate the same volumes offshore – 12.9mn metric tons/year for Mozambique LNG and 15.2mn mt/yr for Rovuma LNG – would be difficult.

Even for smaller capacity, he pointed to challenges related to storms and additional offshore maintenance requirements.

“There's a whole host of reasons why you’d want it onshore,” he says.

Another potential solution suggested by Ackerman was some sort of consolidation between the two onshore projects.

“There should never be two competing LNG projects in Mozambique,” he says. “It would be better operators work together to minimise their footprint.”

This would be a major overhaul of current plans, however. Ackerman also suggests that if the attacks keep escalating, Total still has the option to walk away altogether, having not yet made the bulk of the investment that has been earmarked for Mozambique LNG.

Once again, such a move would be a dramatic one, and something the Mozambican government would be keen to avoid.

“This is an important economic project for the government,” says Feer. “If they don't get these projects built, I think they're going to have some real problems economically. They're pretty heavily indebted … there's a lot at stake for Mozambique, to make this work,” he adds.

“I would assume that the companies would be looking for the government to be upping its game fairly soon, and to be able to show that they're getting the situation under control,” says Feer.

Whether the government has the capacity to contain the insurgency and discourage LNG developers from leaving is a different question, though, and the companies will be watching closely as they consider their next steps.