[NGW Magazine] The Future of LNG

This article is featured in NGW Magazine Volume 2, Issue 19

By Charles Ellinas

The LNG industry is trying to figure out what is the safest way to manage the temporary oversupply while avoiding a shortage and associated price spikes early next decade.

As the production surplus of LNG begins to rise, questions are being asked about how to deal with it in a way that does not destroy value. The industry is asking where are the markets heading; what will be the impact of US LNG; and can new markets and China absorb excess LNG.

These were the topics discussed at two conferences in September: one in Singapore organised by CWC (NGW 2/18 p5) and one in London, LNGgc conference organised by KNect365 Energy.

According to Monica Zsigri from European Commission’s (EC) Directorate-General for Energy, the EU sees LNG and storage as key tools to achieve diversification, flexibility and security of supply.

Monica Zsigri (Image credit: Charles Ellinas)

The objective is to ensure all member states have access to LNG and to make the EU attractive for LNG. This is being achieved by completing the internal energy market and ensuring access to liquid regional hubs, especially for regions which are not well connected.

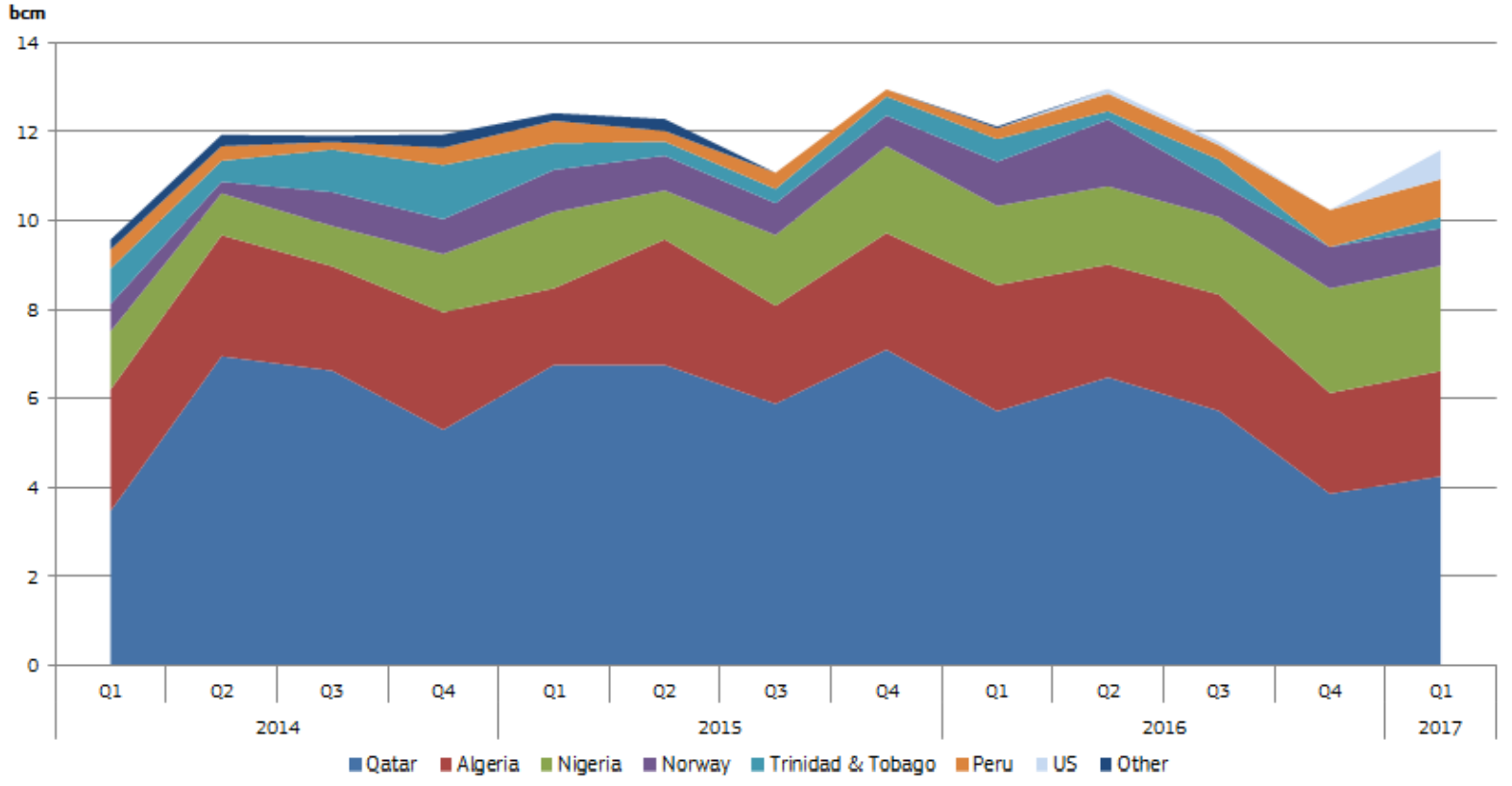

EU’s natural gas imports are expected to remain stable at about 300bn m³/yr up to 2040 and decrease rapidly after that in response to climate policies. LNG’s share was 12% in Q1 2017, down from 14% in Q1 2016 (Figure 1). The share of US LNG in Q1 2017 rose to 6%, providing additional supply diversification.

Higher spot prices in Asia and lower piped-gas prices meant that the traditional suppliers, Russia, Norway and Algeria, increased their gas exports to the EU.

Figure 1: EU LNG imports by supplier

Source: Bloomberg/Poten & Partners

Imports to Malta and Poland are not included; imports coming from other EU Member States (reexports) are excluded

EU LNG import capacity is considered to be sufficient under any supply scenario. Moreover, the EU is well on its way to a resilient gas system, up to 2025, that can respond to any supply shocks. As a result, assuming that projects identified in EU’s energy strategy are implemented, no new investments are envisaged.

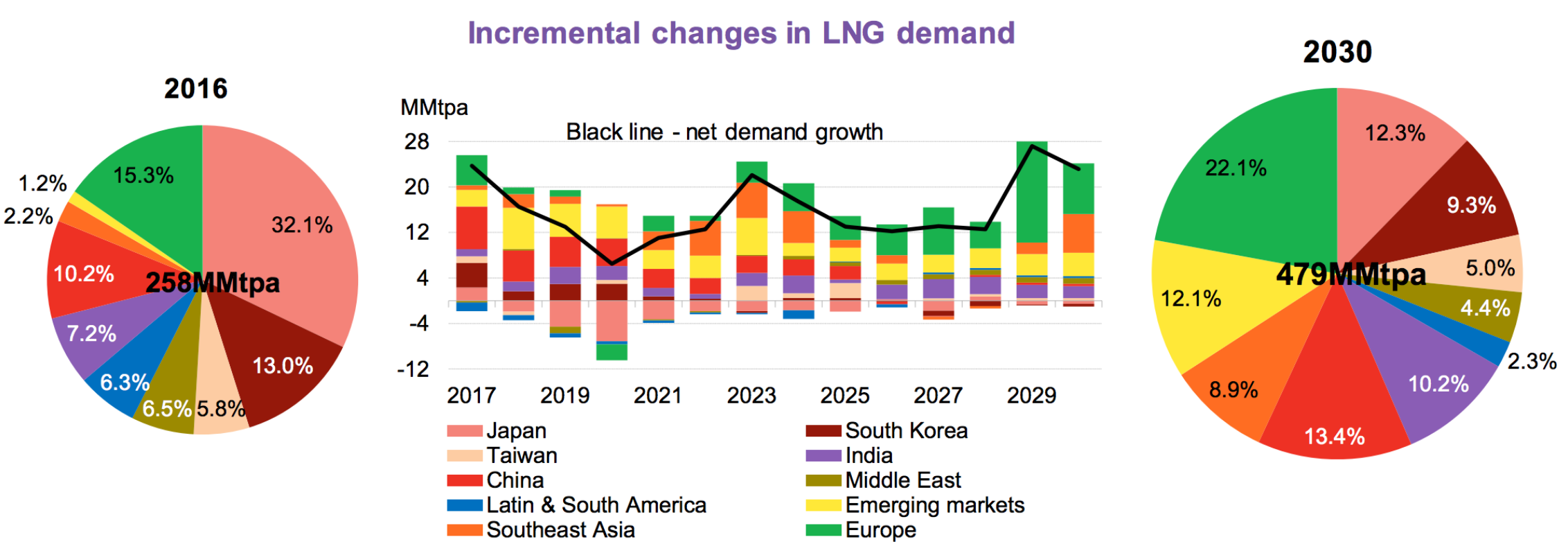

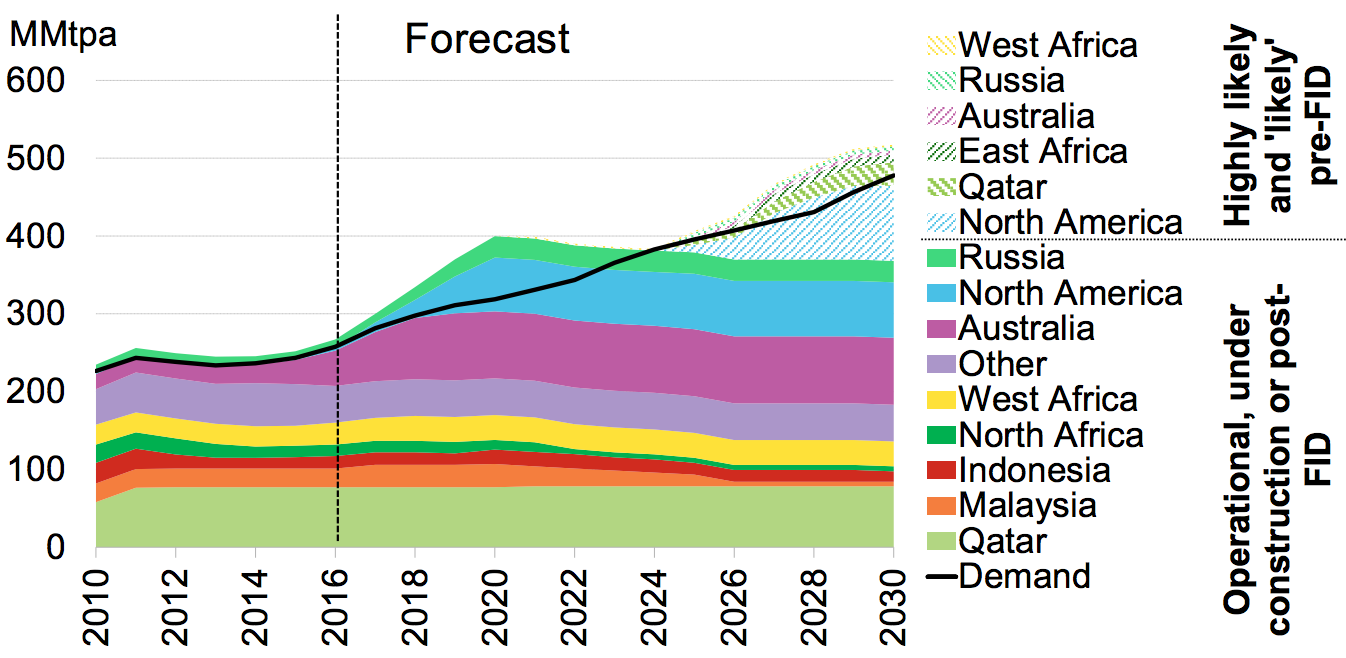

Figure 2: Global LNG demand 2016 to 2030

Source: Bloomberg New Energy Finance, Poten & Partners, Customs.

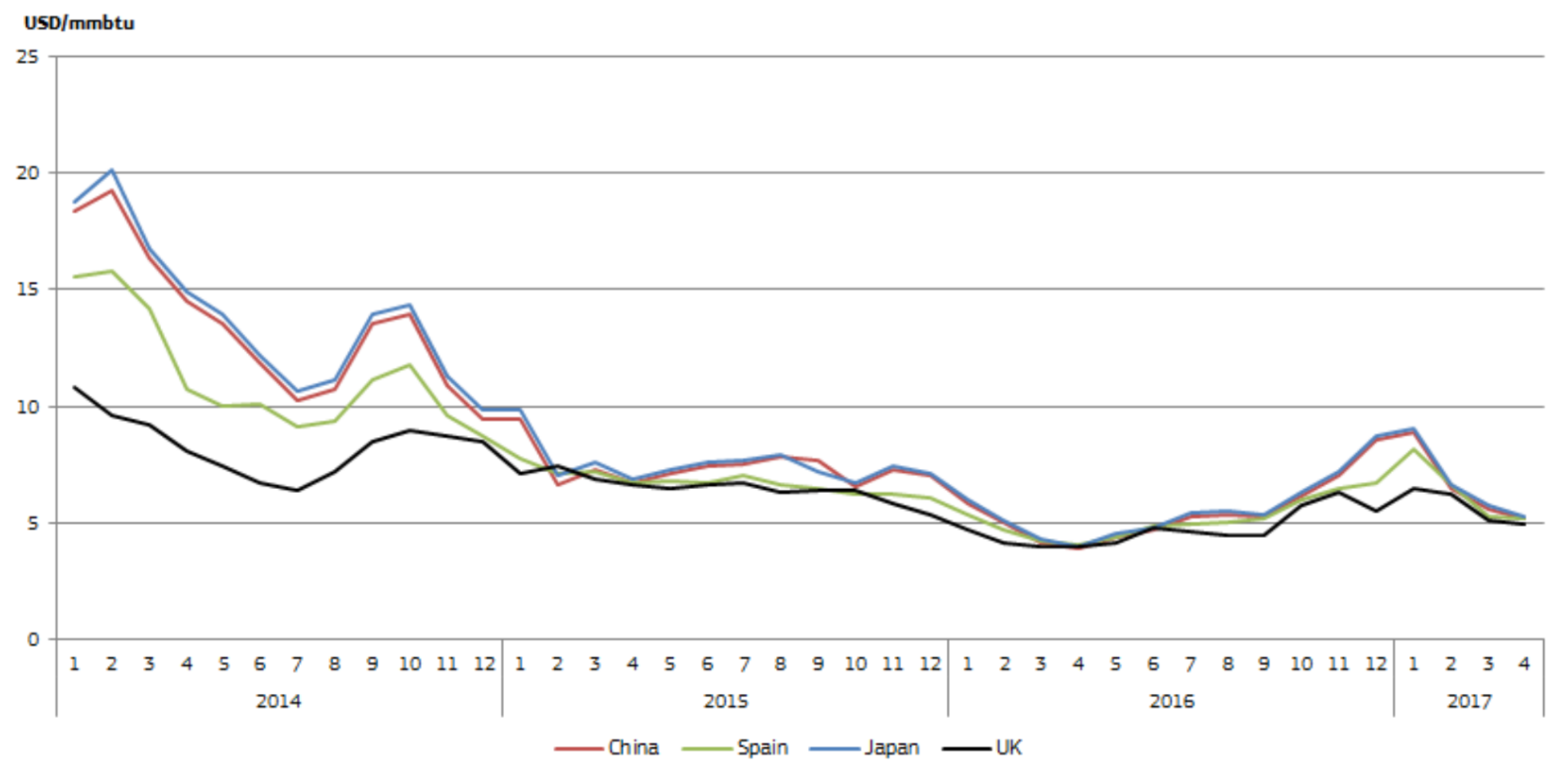

Europe has not become the dumping ground some expected, because other parts of the world have been more attractive in terms of LNG spot prices, particularly southeast Asia (Figure 2). In addition, prices have been weakening and converging as a result of new supplies (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Landed spot LNG prices

Source: Thomson-Reuters Waterborne

Total’s head of LNG, Patrick Dugas, spoke about the challenges of operating in the new, far more competitive, markets: “As a matter of fact, the LNG industry is mutating nowadays with fierce competition with different kinds of LNG players. We have the trading houses who have benefited from the additional production and excess LNG volumes in recent years. We have the portfolio players, we have the gas producers and the historical utilities. Some of the historical buyers have even become sellers because of the lack of their domestic demand, which has been a change in the market. Lastly, our industry has witnessed major consolidations which have created very big players such as Shell [which bought BG] and Jera in Japan. In this period of LNG surplus, you need to pay the utmost attention to customer needs, starting with the best flexibility at a competitive price.”

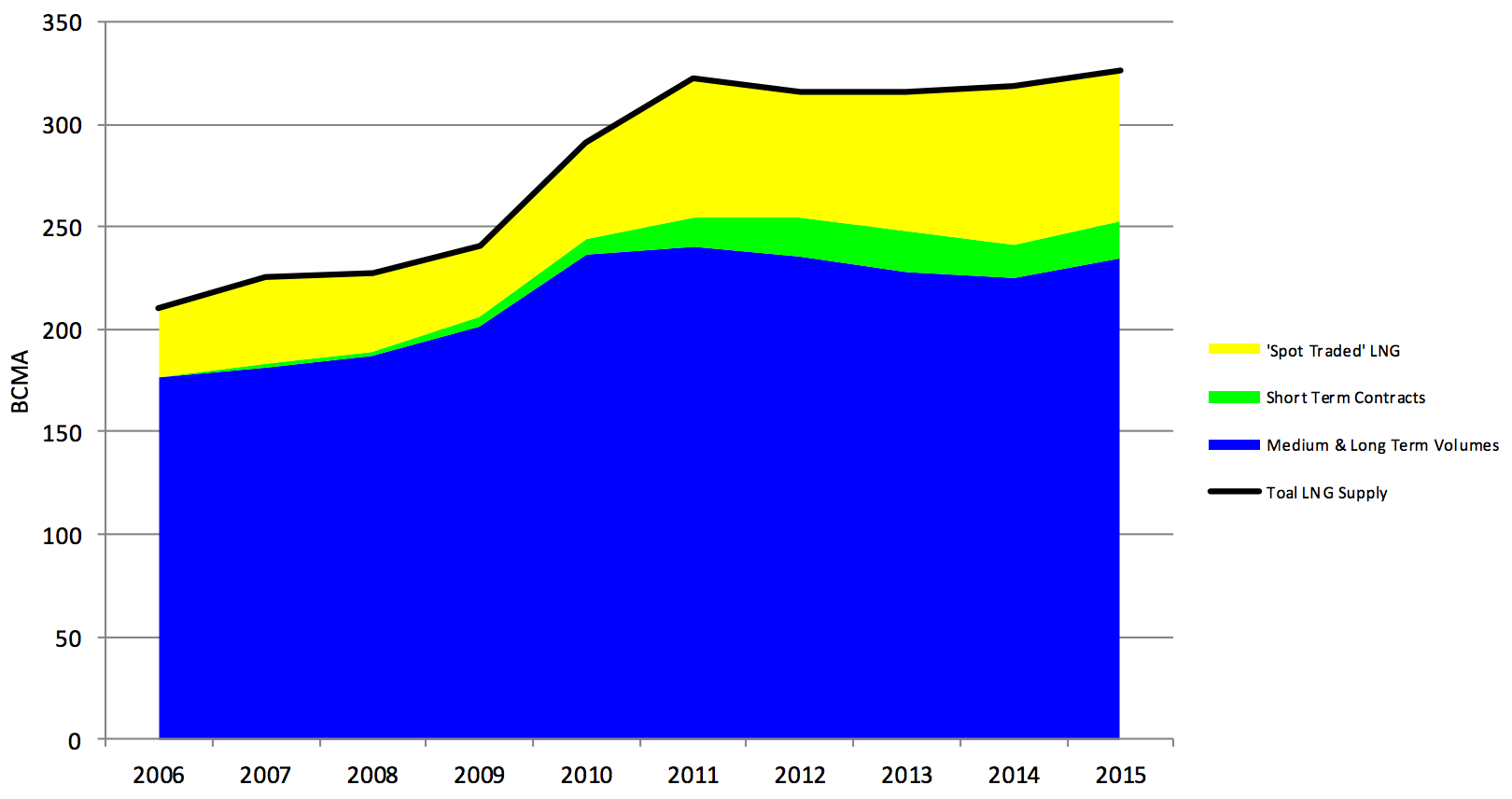

Dugas also addressed key challenges being faced by the LNG industry: “I would say that the key challenge is to understand first the needs of the LNG customers as a buyer or a seller. The LNG market is becoming more liquid with more opportunities to offer greater flexibility. The short and midterm deals represent nowadays close to 30% of the LNG traded around the world. The buyers, at least some of them, have indeed a tendency for the time being not to commit too much on the long term but rather on the spot or the midterm basis.”

The evolution of spot LNG markets and prices and its impact on global LNG trading was taken up by Repsol’s Carmen Lopez-Contreras. But what is spot? In the LNG market there are many diverse definitions of the spot market, all of them dependent on the length of the supply deal. The most frequently used spot definition is supply contracts with duration not exceeding one year. These are mostly done through public tenders, as opposed to longer-term contracts which are based mostly on bi-lateral deals that are mostly oil-indexed. Spot LNG trading has benefited from emergence of portfolio players and traders. But at times of great uncertainty such as today, for some even 18 months is a very long time to contract for.

A consequence of the glut in the LNG market is that contracts are becoming more flexible and continue to fall in size and duration. As Contreras observed, “Five is the new 20 for the duration of LNG contracts.” In addition shipping costs are coming down as more ships come into the market. These factors are driving spot trading up (Figure 4), and prices down (Figure 3), and are leading to the growth of a more liquid spot market.

Figure 4: Global LNG supply by contract duration

Source: GIIGNL

Spot LNG made up 18% of total imported LNG volumes in 2016, increasing from 15% in 2015. With many longer-term LNG supply contracts due to expire in the coming years, the move toward more spot trading is likely to increase.

This is helping narrow the gap between European and Asian spot prices and this price convergence is expected to continue. The growth in US LNG exports, as well as the emergence of new importers, is expected to accelerate the growth of spot LNG supply. But for suppliers, short-term contracts make the future uncertain and financing new LNG projects a challenge.

Can US LNG compete in today’s market? The case was made by the CEO of Texas LNG Vivek Chandra. Based on the today’s Henry Hub gas price of $3/mn Btu, the free on board cost of US LNG is estimated to be about $6.25/mn Btu. Once shipping costs are included, the all-inclusive landed price of US LNG is not competitive against either Europe or Asia spot prices.

However, there are compelling arguments that Henry Hub prices will fall from today’s levels. Chandra based this argument on US gas production, especially shale gas. This is becoming more efficient and is growing faster than US gas demand, which is remaining relatively flat, increasing pressure on gas prices. This is especially the case with associated shale gas that needs to be disposed of, if it is not to slow down the growth of shale oil production.

The salvation to this excess gas lies in increasing LNG exports. Chandra said “Never bet against the US upstream producer! They are the most efficient and innovative in the world and will find ways to compete at any price. Marcellus is already one of the biggest fields in the world and will grow by 45% over the next few years.”

There is also a compelling argument that oil prices will rise from current levels, above $50/b. Both factors will increase competitiveness of US LNG. However, on price US LNG cannot compete against Russian pipeline gas.

But global LNG demand growth is robust, particularly in Asia, which is less accessible to Russian pipeline gas. In addition:

Global LNG supply will set a new record this year, the fastest since 2011;

In the first six months of 2017 global LNG trade increased by 13% year-on-year to 144mn metric tons;

By 2025 China, India and southeast Asian countries will import more LNG than Japan, South Korea and Taiwan combined;

China imports so far this year have seen a 15% growth;

FSRU import capacity is increasing and will reach 20% of global LNG import capacity by 2022. FSRUs are easier and faster to deploy, facilitating entry of new importers into the market;

But only 5.7mn tons/yr new LNG term contracts have been signed so far this year, the lowest figure since 2010.

The main reason is lack of interest by buyers to commit to long-term contracts, making it difficult to support new FIDs. The chairman of Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, Howard Rogers, agreed, adding that European buyers will mostly pay hub prices and, with uncertainty about future demand, Asian buyers do not want long-term contracts.

However, despite the expected LNG glut, so far all produced LNG has been finding buyers. Possibly as a result of low prices, the flexibility offered by FSRUs and the drive towards emission reductions, demand growth has been keeping pace with supply growth. This suggests caution when predicting LNG market over-supply.

However, current expectation, and perception, of an LNG glut has made basing supply-side investment decisions on established market fundamentals difficult, delaying new projects.

Howard Rogers, Chairman of Oxford Institute for Energy Studies

Assuming this continues, and depending on how fast Asian and European LNG demand grows, new LNG supply will be needed possibly by 2023 or by 2027 at the latest, leading to the next ‘LNG wave’. There was a broad consensus that the tipping point may be around the mid-2020s.

Developing new LNG projects typically takes four or five years. So to meet this new LNG demand FIDs must be taken by 2019 or by 2023 at the latest. But there are still big uncertainties and dilemmas. The appetite from buyers for long-term contracts is not there.

This new, evolving, market has led to the emergence of portfolio-players, mainly majors and large traders, who buy LNG volumes from various projects and combine them together to sell to end-users. By optimising their LNG supply portfolios, they are able to offer flexible and competitive terms in their sales contracts.

With gas caught between renewables and coal, and LNG competing with pipeline gas, means that prices will stay low. Low coal prices, particularly in Asia, impact directly gas demand. If anything, there may be more demands by buyers for price re-negotiation and for shorter-term and spot contracts.

As a result, the next ‘LNG wave’ may come from the US where increasing shale oil and gas production will put more pressure on prices, but also on the need to export gas, as stated earlier. With a backlog of regasification facilities waiting to be converted for export, aggressive cost-cutting in liquefaction plant costs and lower upstream costs, and positive government support, new US LNG FIDs may be on the way (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Global LNG demand/supply capacity balance

Source: Bloomberg NEF

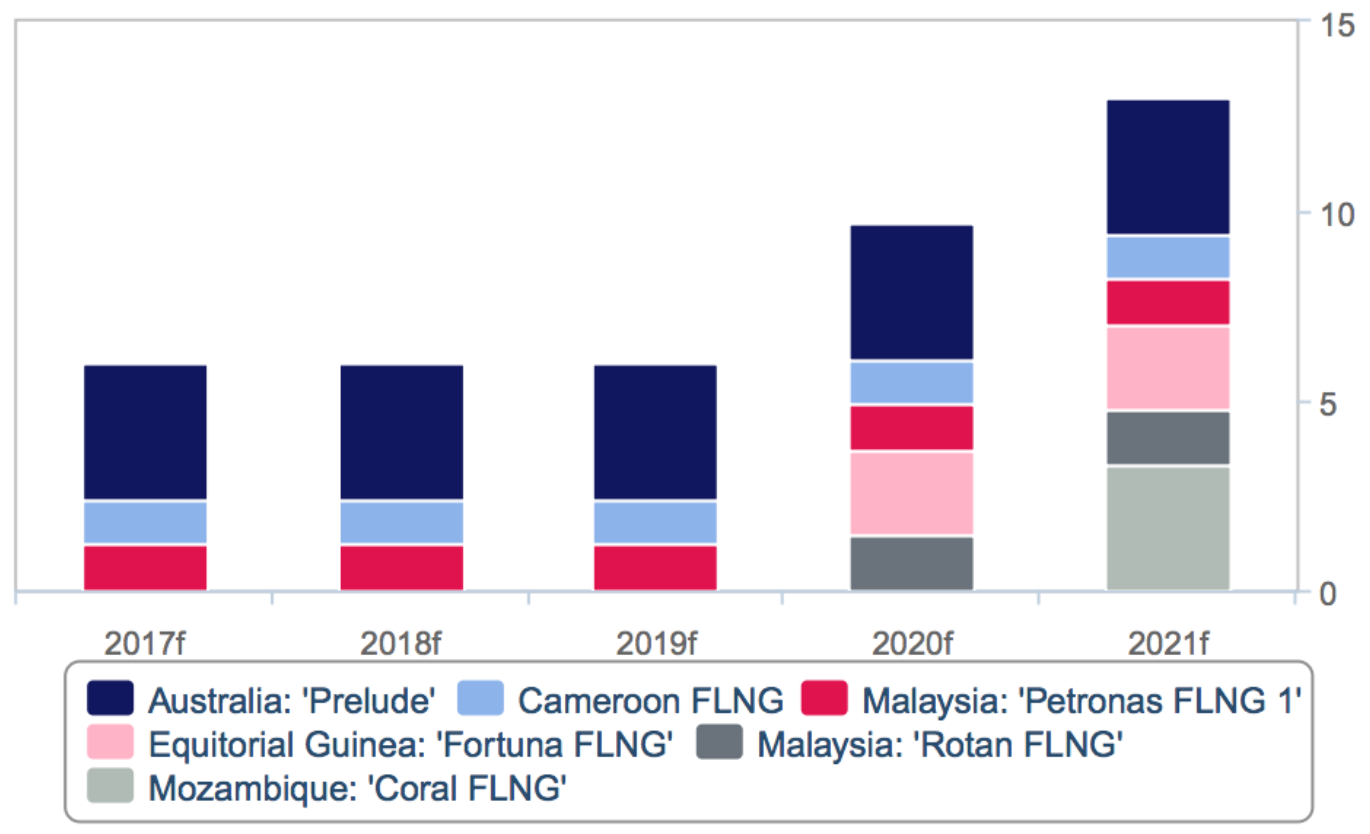

Qatar, having awoken from its self-imposed moratorium, is on the way to adding more, lowest-cost LNG to the market, starting with the recently announced 30% production increase, equaling another 23mn mt/yr output. And so are expansions of existing Russian LNG plants, aided by tax exemptions, and possibly also the debottlenecking of liquefaction plants in Australia. Floating LNG also appears to be gaining momentum, especially in Africa, even if projects tend to be smaller than land-based plant, Figure 6.

Figure 6: FLNG capacity additions (in mn tons/yr)

Source: BMI

New project FIDs could more than satisfy the expected gap in demand during the second half of the 2020s. But the question still is: can future LNG prices be high enough to allow such new FIDs to be taken?

Another possibility is that as the LNG market tightens, portfolio-player majors could develop lowest-cost accessible projects, balance-sheet financed, and sell on a spot, short and medium-term basis. As Rogers observed, “Independents and banks face a ‘Darwinian adaptation challenge’ in the absence of the familiar oil-indexed long-term contract paradigm. Adaptation is likely, but at what pace?”

The issue of LNG over-supply was covered by Wood Mackenzie’s research director Murray Douglas. He said Asian LNG demand and growth cannot keep pace with supply and this is even though Asian LNG imports have exceeded forecasts, especially in China.

Europe is brimming with gas, especially with Gazprom responding flexibly and rapidly to demand as it develops and increasing market share, with little upside for gas demand to increase beyond this. As a result, LNG over-supply remains inevitable into the 2020s. And with continued over-supply the downward pressure on LNG prices will also continue.

Lower prices have led to a rise in LNG imports by China, Pakistan and Bangladesh. These and other new markets are forecast to grow as long as gas remains competitive against coal and renewables. By 2020 China may be importing over 60bn m³/yr of LNG, coming close to Japan.

This was the message of the head of Japan’s Jera, Yuji Kakimi. Jera was the joint venture launched in 2015 with the merger of two giant buyers of LNG Chubu Electric Power and Tokyo Electric Power. The rationale was to concentrate demand and it was hoped, secure lower prices.

He warned producers that they need to become more competitive on price and allow for more flexible contracts if they want to usher in a ‘golden age’ of gas in Asia.

He told the Financial Times in late September: “The price of LNG has to be reasonable and there needs to be flexibility…If the market lacks these things the golden age will never come.” He then went on to say: “Compared to coal, as a fuel source for electricity, gas is about 1.5 times more expensive, even at $6/mn Btu. Can emerging markets, which are looking to grow, really push for environment over economics? At $10/mn Btu…it isn’t economically competitive at all.”

Figure 7: World’s top LNG buyers

Kakimi said that US exports have bridged the gap between the previously disconnected gas markets around the world. While Asia, led by Japanese buyers, traditionally relied on LNG mainly from Australia, Qatar, and Malaysia, Europe had its gas supplied mainly through regional pipelines.

Now, Cheniere LNG, which started exporting from the US in February 2016, has a global reach supplying LNG to 25 countries, with transparently-set prices and shippers not bound by destination clauses. This, the spot market and the LNG over-supply are likely to accelerate the transition of global LNG into a more regular commodity market.

Charles Ellinas