[NGW Magazine] IEA Sees Glut Fuelling Demand For Flexibility

This article is featured in NGW Magazine Volume 2, Issue 20

By Mark Smedley

An International Energy Agency gas security review contains fascinating analysis, and forecasts of key LNG market trends. The over-supplied market was able to take supply shocks in its stride.

The International Energy Agency’s second Global Gas Security Review (GGSR), released October 18, argues that, while gas markets are well supplied, their transformation from regional systems to more globalised and interdependent markets is creating new security challenges.

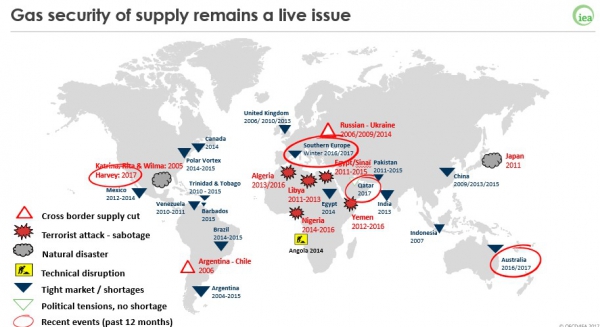

The GGSR considers recent gas balancing issues and risks, including the stressed situations in natural gas and power markets experienced by several southern Europe countries in the winter of 2016-2017; diplomatic tensions between Qatar and some neighbours; and supply risks posed by recent hurricanes on the US energy system, which in future years may extend to Mexico’s too.

The 102-page report details how importing countries in mature and well-interconnected markets can still experience sudden shocks that stress the market, even in the current low-price environment, with suppliers exposed to low-probability high-impact events with potentially serious consequences.

“From cold spells in southern Europe, to hurricanes in the Gulf of Mexico, to diplomatic tensions among Gulf countries, energy security is impossible to ignore,” said IEA executive director Fatih Birol, presenting the review at the LNG Producer-Consumer conference in Tokyo.

Graphic source: IEA/Peter Fraser

Disaster, sabotage, and supply cuts

“Gas security issues are nothing new -- whether it’s cross-border supply cuts, sabotage of infrastructure, natural disasters, tight markets, or political tension. There are always risks to gas security,” cautioned Peter Fraser, head of the IEA’s Gas, Coal and Power Markets division October 16 at an embargoed press briefing two days prior to publication.

The review, he said, examined events in southern Europe last winter when cold weather stressed gas and power supply systems, in the US after Hurricane Harvey, in Australia where gas security matters are quite complex, and the political tensions surrounding Qatar.

Fraser noted how the main lesson learned by the IEA in southern Europe was on the timing of supply. He pointed out how, in both Spain and Greece which had gas supply emergencies because of the cold weather, “extra LNG was ordered to help make up the shortfall – but by the time that the LNG arrived, the worst of the crisis had passed.”

In the US by contrast, Hurricane Harvey caused no spike in US natural gas prices, because the storm caused not only a supply interruption but also a demand abatement, in addition to which there are the major shale gas supplies from the Appalachian basin in the northeast US. These were not producing when the last big disruption hit the US Gulf with Katrina in 2005.

Fraser noted that Mexico was affected by Harvey, although not greatly; but the potential for disruption to Mexico could increase as it becomes more dependent on US piped natural gas imports.

US LNG exports were interrupted for several days, he added, with ten ships forced by Hurricane Harvey to delay loading at Sabine Pass. Although this had minimal impact on markets, Fraser noted: “LNG exports from the [US] Gulf are expected to grow strongly, even quadruple, in the next five years, suggesting that future events may have a more significant impact on global LNG markets.”

Flexibility in contracts

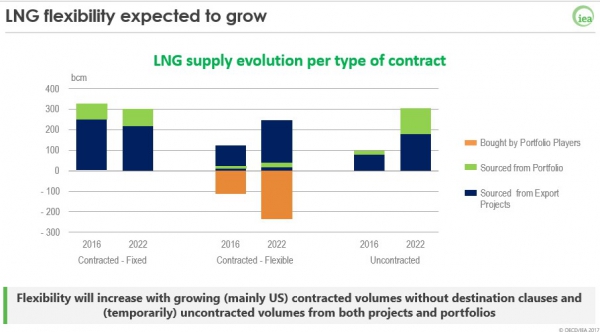

Comparing 2014, 15 and 2016, the IEA gas chief said that a smaller share of new LNG contracts had a fixed destination clause. The report forecast that contracts with a fixed destination are expected to decrease overall. Additionally, the duration of the contracts is getting shorter and shorter.

“The current situation of oversupply in LNG appears to be a significant driver in providing LNG buyers with more flexible contract arrangements,” said Fraser.

Such flexible contracts would come primarily from US projects, and to a lesser extent from Australia, Russia, Qatar and Indonesia. He said this trend towards greater volumes being contracted without destination clauses would continue, as US exports rise.

Added to this, portfolio players – including traders – are picking up a growing share of the global market. However, Fraser noted that some contracted flexible volumes could be only temporarily without fixed destination, as some will then become locked by portfolio suppliers into fixed destinations (such as Brazil, by Ocean LNG; or Ghana, by Gazprom).

LNG supply evolution per type of contract, 2016-22 (Credit: IEA report, Fig.2.14)

On top of this, uncontracted volumes will remain a significant question for the coming years, which the IEA expects to triple to around 300bn m³/yr by 2022. As Fraser explained: “there is more volume out there than there is our expectation of available demand, so there’s going to be an additional head of pressure on the market.” The IEA meanwhile expects the share of oil indexation in overall LNG export contracts to decrease, but forecasts that it will maintain its share in contracted exports.

Looking particularly at Asia, the IEA says the volumes imported by Asian countries have very limited flexibility – at some 5% of the total in 2016 – but this will improve with the expiry of legacy contracts and development of flexible North American contracts. It says the Asian trend will diverge between China and India on the one hand, both of which will add contracted volumes; and Japan on the other. Now over-contracted in LNG, it is not expected to renew all of its existing inflexible contracts that are due to expire in the coming years.

The Japan Fair Trade Commission ruling in June 2017, banning flexibility restrictions in new contracts – and a similar enquiry now by the Korea Fair Trade Commission – are “likely to further reinforce this push for increased flexibility among traditional Asian importing countries,” the IEA review adds.

Even further west, producers who have long resisted efforts to make their LNG supply contracts more flexible may have to adapt. The report notes: “If Algeria also wishes to increase its contracted LNG exports, Sonatrach will most probably need to align with its competitors and offer similar contract flexibility.”

Interestingly, Sonatrach CEO Abdelmoumen Ould Kaddour October 17 made remarks in London indicating he is thinking along these lines, saying that future gas/LNG agreements with companies “will not be indexed to oil prices and will not be long term” and that Sonatrach will consider joint ventures with marketing firms – a possible relaxation of its Algerian piped gas sales monopoly.

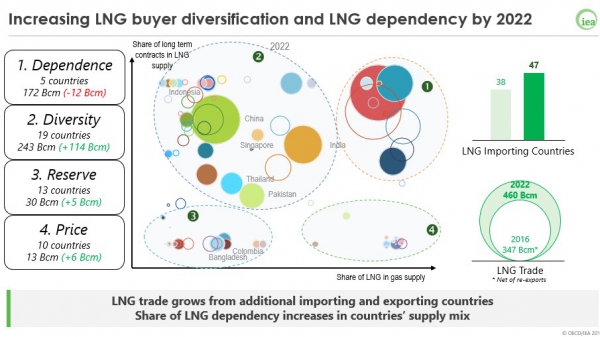

Supply Diversity: the key LNG growth promoter

One piece of analysis novel to this latest IEA GGSR divides buyers into four main groups: those driven by their LNG dependency; those seeking supply diversity; those who dip into the market now and then (reserve buyers); and those sensitive to price. It shows that markets that need diversity will generate the biggest LNG demand growth out to 2022.

The largest members of this group last year were China, India, Spain, UK, France and Mexico. It was the largest of the four groups, ahead of ‘Dependency’ comprising Japan, Korea and Taiwan who have no reserves or pipeline imports. The ‘Reserve’ group included hydro-generators Brazil and Argentina – which source LNG when drought strikes, but in some years are out of the market – along with Egypt, Kuwait and the UAE.

The ‘Price-sensitive’ group is the smallest of the four and includes Jamaica, Jordan, Lithuania and Puerto Rico that turned to LNG only when prices plunged, but which may stop buying again in the 2020s if LNG becomes expensive.

By and large, neither the Reserve or Price-sensitive groups are interested in long-term contracts. By 2022 the IEA expects global LNG imports to have reached over 460bn m³ into 47 countries (up from 355bn m³ in 2016) and now breaks down the LNG market anew, according to the buyer types. It finds that the ‘Diversity’ group will be by far the largest, both in absolute volume and in growth rate since 2016. Pakistan and Thailand will be substantial ‘diversity’ importers by 2022, though still dwarfed by expanding China and India. Few new recruits will join the Dependency group, whose volume size will decline. The Price-sensitive group will stay small in volume, but several small island or African states will join it, including Ghana, Haiti, Namibia and Panama. The Reserve group’s big recruits by 2022 will be Bangladesh and Colombia, but the Philippines, Greece, Sweden and Israel will also be there.

Graphic source: IEA/Peter Fraser. Comparisons are relative to 2016

Offline LNG capacity

A further interesting observation in the GGSR is that LNG export (liquefaction) plants’ availability globally was 96% in 2015, relatively stable at 95% in 2016, but fell to an anticipated 87% for 2017. The report says the drop is partly explained by the rapid addition of capacity in 2017. But it notes that, especially in the US and Australia where plants are run by companies rather than state entities, “the industry will need to operate with a high availability factor to cover its short-run marginal costs in a low gas price environment.”

Fraser argued October 16 that, the fact that the global market can manage at just 87% availability is actually a “good sign” of the LNG market stability – that there is “spare capacity” in the global system. Indeed, the report shows that, in countries like Egypt where 97% of nameplate liquefaction capacity was not used in 2016 and Algeria where 27% was not – it was because of domestic imperatives; both are using more of their own gas, either in industry or to generate cleaner power.

His point – that it’s better for the world’s liquefaction plants to run at less than 100% than at 100% -- may be valid for the global market, LNG traders and gas-consuming nations: “It’s a measure of under-utilisation of the system rather than a measure of extra mechanical, technical or other problems. It’s just really that we have a glut.”

But the fact that Yemen LNG has not produced for 30 months does not help global security. No blame can be put on YLNG shareholders, led by Total, for declaring force majeure in mid-April 2015 and shutting a complex due to a civil war fuelled by external players such as the Saudis and Iranians.

An outage of 2% of global liquefaction capacity – for that is what the 6.7mn mt/yr (9.1bn m³/yr) YLNG plant opened 2009 represents – even if largely forgotten by traders – and factored in by offtakers Engie, Kogas and Total – is not even a positive sign of LNG market stability. The Yemeni capacity cannot be spurred back online by ‘market signals’. Rather it reflects, just as during the Cold War when regional conflicts between the US and USSR dragged on in places like Angola for decades, how economies that should be harnessing their natural resources and exporting LNG are still being blighted.

“In Yemen there are no winners on the battlefield. The losers are the Yemeni people who suffer by this war,” stated Ismail Ould Cheikh Ahmed, the UN Special Envoy for Yemen October 10. Losers from the YLNG outage include not just Total and US Hunt Oil but also the Yemeni people and its state pension fund that are also equity partners. Experts expect the number of cholera cases in Yemen to surpass 1mn by the end of this year, from some 815,000 now – including over 2,150 deaths.

Mark Smedley