[NGW Magazine] US LNG vies with LatAm Output

This article is featured in NGW Magazine Volume 2, Issue 20

By Sophie Davies

US exports of LNG from the Sabine Pass could see competition from growing levels of domestically produced natural gas in some Latin American countries, experts say.

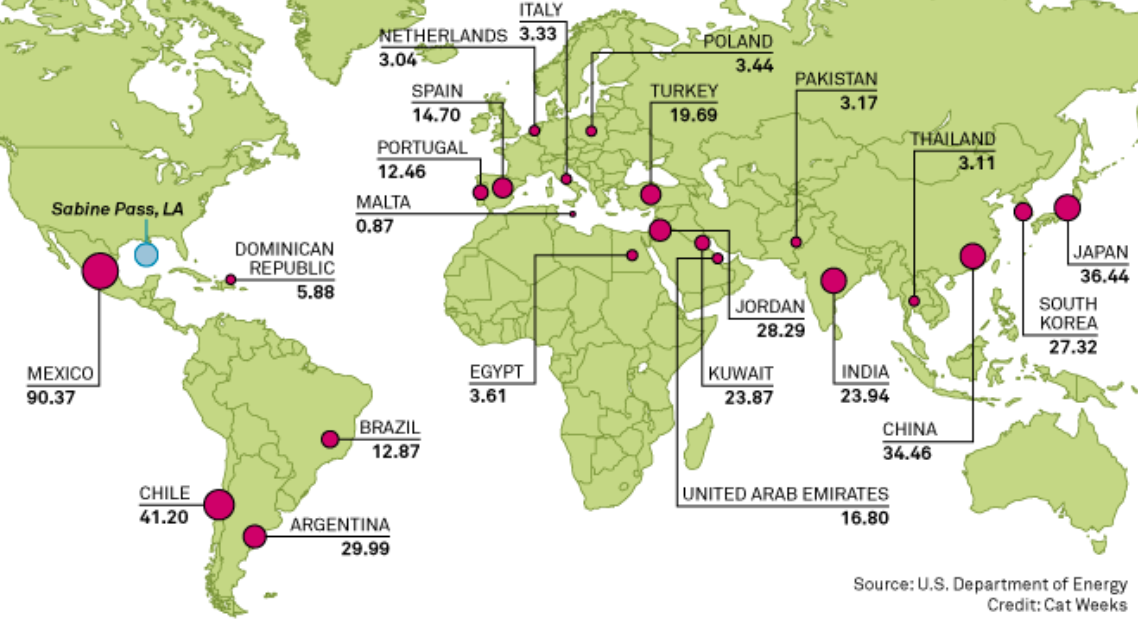

US exports started up from Cheniere Energy’s Sabine Pass export plant --– so far the only LNG terminal in the US – on the Gulf Coast last year, and over the course of 2016, a total of 1.63mn tonnes (mt) arrived at terminals in Mexico, Argentina, Brazil and Chile, according to shipping tracking information. Of that, Mexico received the most with 0.48mn mt, followed by Argentina with 0.33mn mt, Brazil with 0.18mn mt and Chile with 0.59mn mt.

Colombia is the only other LNG importer in South America, and has received one cargo to date.

In the first nine months of this year, Mexico’s imports of US LNG more than quadrupled to reach 2.24mn mt, partly owing to problems at pipelines affecting throughput of natural gas deliveries from the US, boosting LNG imports. However, imports by Argentina, Brazil and Chile so far this year are not significantly higher than last year – at least, not in the first nine months. By the end of the third quarter, Argentina had imported 0.31mn mt, Brazil 0.15mn mt and Chile 0.32mn mt of LNG from the US.

Chile is the market in the region that has been “most reliable in terms of total imports” so far, but its future will mostly depend on Anglo-Dutch Shell and how it optimises its portfolio there, according to independent LNG consultant Andy Flower.

The level of US LNG imports expected into Brazil and Argentina in future is a little less certain, as the domestic gas markets in these countries develops, he said. This could lead to a struggle between domestic gas producers and US LNG exporters.

Argentina’s president, Mauricio Macri, who has shaken up energy policy since assuming power in late 2015, is encouraging exploration and production and subsequently there has been “some increase” in gas production there, Flower said, and so the country is already importing less gas.

Argentina has traditionally imported its pipeline gas from neighbouring Bolivia, and some LNG from Trinidad & Tobago. The country, once one of South America’s biggest gas exporters, now imports around one fifth of its gas needs.

Bolivian gas imports to Argentina, which are far cheaper than imported LNG at current prices, would benefit from more temporary flexibility between seasons in future, consultants at Wood Mackenzie told NGW.

Argentina would need to put a lot more investment into the Vaca Muerta shale formation to put the country in a position where it could significantly lower Bolivian imports, he said.

One of the largest shale deposits in the world, Vaca Muerta in Neuquen province contains around 308 trillion ft³ of shale gas and 16.2bn barrels of shale oil, according to the US Energy Information Administration. A group of companies that includes oil majors BP and Shell agreed to collectively invest $5bn in the formation this year and $15bn/yr from 2018.

However, if Argentina is “successful at ramping up” Vaca Muerta gas in future it would not only have more gas for itself but could also send more pipeline supplies to Brazil, which could alter the continent’s supply fundamentals, WM added.

Brazil, for its part, is producing more gas domestically, meaning it needs to import less LNG, but its demand also depends on the level of rainfall in the country, said Flower. The main use of LNG in Brazil, Latin America’s largest country, is for power generation. A few years ago, a major drought led to low rainfall levels and the need for more imported gas. But more rainfall has lowered the requirement for imported gas in recent years.

The “scale and proximity” of US LNG to Latin America could “open opportunities for new players in Latin America to access direct energy supplies,” WM told NGW. “There are also many companies with existing US capacity or proposing to develop new LNG capacity in the US that are pursuing opportunities in the region,” the consultancy added.

However, US LNG imports into Brazil will face competition from Nigeria and Trinidad & Tobago, which are both already strong LNG players. Nonetheless there are international LNG players like BP and Shell that are seeking to develop LNG-to-power infrastructure, which could develop the market.

The market could also evolve as other players get involved, for instance those domestic industrial players in Brazil that are seeking opportunities to go around state-run Petrobras to source energy, WM added.

Fears have mounted in recent months over whether Brazilian demand for Bolivian gas may begin to wane, after officials said that Petrobras could require less imported gas from its neighbour in future as output from its offshore fields rises.

Nonetheless Petrobas still has not confirmed that announcement, so the quantities are not yet defined, cautioned WM. Petrobras currently imports 30mn m³/d of Bolivian gas under a long-term contract and there is market speculation that its supply could be more than halved to around 14mn m³/d when that expires, the consultancy added.

In addition, there are many local distribution companies that are eager to buy gas regularly from Bolivia – as well as some power plants – which could replace the supply lost to Petrobras.

If Brazilian demand does wane, other options for Bolivian exports do exist, though they are limited. Most of Bolivia’s neighbours produce their own oil and gas; or they have complicated historical relations with the country, like Chile. Paraguay has been touted as a possible buyer of future Bolivian gas supplies but even so its demand would be small.

Bolivia’s gas exports are just one area of the South American gas market that are set to change in coming years, as the global LNG business grows and offers greater competition to domestic gas markets in the region.

Of all the domestic markets that are evolving, Argentina’s development of its shale resources looks set to be the biggest game-changer in the region, though procuring enough investment for such a large formation could still present a challenge and may leave a window for increased LNG imports from the US and elsewhere.

Sophie Davies