[NGW Magazine] UK emissions blindness

This article is featured in NGW Magazine Volume 2, Issue 21

National obligations to cut carbon dioxide emissions have been allowed to override more pressing worries about health-related particulates. A new UK government report also falls into that trap.

The UK government released its Clean Growth Strategy (CGS) October 12, with some radical ideas about UK homes and future carbon capture and storage. But it does not acknowledge how low-emission gas and LNG in transport can further improve air quality in Britain's cities and ports.

The 165-page document, published by the government's Business Energy and Industrial Strategy department (Beis), outlines ways in which the UK might reduce its greenhouse gas emissions by at least 80% by 2050, relative to 1990 levels, in line with a commitment in the UK’s 2008 Climate Change Act.

According to the report, the UK is over halfway to that goal, having cut emissions by 42% since 1990 while its economy grew by two-thirds. The UK, in doing so, now has the most offshore wind generation built anywhere, with about 40% of total worldwide offshore installed turbine capacity, the report states citing International Renewable Energy Agency data.

Low-hanging fruits have already been harvested. This means the strategy document now proposes tougher plans to expand use of renewable and non-carbon energy, and to kick-start the moribund UK carbon capture use and storage (CCUS) sector.

However, despite its lengthy discussion of how to de-carbonise UK transport, the report makes no mention of any role for gas, or LNG-fuelled trucks or ships, in marked contrast to plans published in France where, as in the UK, a ban on new petrol/diesel-fuelled cars will be introduced by 2040. Officials say more could be revealed in separate UK transport strategy paper to be published 2018.

Three pathways

One approach taken by the CGS report is to identify ‘pathways’ towards achieving the UK's 80% emissions reduction goal by 2050. So, it sets out three: the electricity pathway, the hydrogen pathway, and the emissions removal pathway.

Under the electricity pathway “there are many more electric vehicles and we replace our gas boilers with electric heating and industry moves to cleaner fuels.” Yes, that could mean no more gas central heating and hot water in UK homes in 2050. This pathway would mean 80% more electricity used in the UK then, compared with now, virtually all from fossil-free renewables and nuclear, with no CCUS.

Under the hydrogen pathway, existing gas infrastructure is used to deliver hydrogen for home heating and to filling stations for vehicles, while “a large new industry supports hydrogen production using natural gas and capturing the emissions with CCUS.”

The report though cautions that whereas “clean fuels such as hydrogen and bioenergy could be used for transport, industry, and to heat our homes and businesses” … “we need to test how they work in the existing gas network, whether they can fire industrial processes” or work in domestic appliances."

Under the emissions removal pathway, “sustainable biomass power stations are used in tandem with CCUS technology,” suggesting possibly a role for some gas-fired power plants with CCUS.

Responding to a NGW request on whether, following press reports, the UK really intends to introduce a ban on domestic gas boilers in 2050, a Beis spokesperson said that – under the electricity pathway – the CGS strategy “does not say that we will ban gas boilers… it says ‘we replace our gas boilers with electric heating and industry moves to cleaner fuels’, this being an end-point scenario -- what the future looks like in 2050 – without prejudice to how we get there. None of the three 2050 scenarios is a fixed policy pathway at this point in time.”

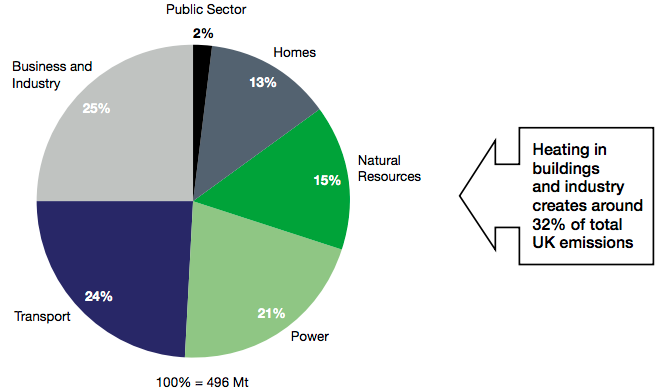

UK emissions by sector, 2015

Source: Beis

Industry associations' wary welcome

UK upstream association Oil & Gas UK welcomed the CGS report, but noted its members had reduced CO2 emissions from production by 30% since 2000: “Meeting demand with domestic hydrocarbons eases our reliance on international resources, ensures we protect security of energy supply and mitigates against carbon leakage.”

It further added: “Gas has transformed the UK’s power sector in recent years, with a significant coal-to-gas switching in the power mix…. This switching made a major contribution to an estimated 20% fall in UK power sector emissions in 2016, underlining the important role gas should continue to play as part of a cost-effective decarbonisation of the energy system.”

The role of network operators in implementing policy change for whichever pathway/s are selected could be significant, so the CGS report notes that energy regulator “Ofgem is making available to GB electricity network companies up to £525mn ($693mn) regulated expenditure in 2016-2021; the goal is to support smarter, flexible networks, from enabling the integration of clean generation through to customer-focussed energy efficiency measures. This builds on previous network company innovation which delivered 4.5 –6.5 times more benefits for consumers than it cost.”

UK industry group, Energy Networks Association (ENA), which represents 15 gas and electricity transmission and distribution networks, said October 24 it has opened registration to two free industry workshops to be held during November in London and Glasgow relating to its Electricity Innovation Strategy. Consultation documents on the networks' Joint Innovation Strategies are being launched in the coming weeks. ENA said that examples of innovation include battery storage and electric vehicle-to-grid projects being developed by electricity networks, and biomethane, bioSNG (bio synthetic natural gas) and hydrogen projects being developed by gas networks.

ENA is also funding opportunities for low carbon innovators with the launch of a call for ideas deliver "carbon or environment benefits" to customers. It said October 30 that is offering up to £20mn/yr through the Networks Innovation Competition (NIC), and the gas networks are inviting third parties to submit their proposals for innovation projects. Projects that have already received part of £41mn already disbursed include low-carbon options for the local gas distribution networks, such as hydrogen, biomethane and bioSNG; using gas as a fuel for transport; and the use of new technologies for operations and maintenance work.

ENA said that decarbonisation is beginning to be viewed as an enabler, rather than a barrier, to reducing energy costs and delivering economic growth.

Carbon capture

The UK’s limited progress in rolling out carbon capture were discussed here a year ago, when a parliamentary advisory group submitted a detailed report on the subject (NGW Vol 1, No.3, pp7-8). Very little has been heard in Europe, beyond Norway, on the subject since.

The CGS now explains “While we have explored ways to deploy CCUS at scale in the UK since 2007, the lack of a technological breakthrough to reduce the cost of CCUS and the cost structures and risk-sharing that potential large-scale projects have demanded has been too high a price for consumers and taxpayers.” It said other governments had reached similar conclusions. Two years ago, the UK scrapped a £1bn ring-fenced capital budget for CCS.

Beis though said in its CGS report that it has invested over £130mn to date in research to develop CCUS in the UK, “supporting the development of technologies including NET Power’s Allam cycle, Carbon Clean Solutions, and C-Capture.”

Of these, it says it provided £7.5mn for early development support to the UK-invented Allam cycle technology used by NET Power which “has the potential to capture 100% of the carbon dioxide emitted at a cost similar to that of an unabated Combined Cycle Gas Turbine (CCGT).” It said in March 2016, construction began on the first NET Power pilot project, a 50 MWth first-of-its-kind natural gas-fired power plant in Texas, expected to start operations in late 2017.”

The CGS report says “We will work with the ongoing initiatives in Teesside, Merseyside, South Wales and Grangemouth to test the potential for development of CCUS industrial decarbonisation clusters”, acknowledges the work of the parliamentary advisory group’s report last year, and commits to “set up a new Ministerial-led CCUS Council with industry” to review next priorities.

The report says the UK government will spend “up to £100mn from the BEIS Energy Innovation Programme to support Industry and CCUS innovation and deployment in the UK, including £20mn of funding available for a carbon capture and utilisation demonstration programme.”

That all looks like beer money, compared to the subsidies once sought by BP on its offshore Miller carbon capture and storage (CCS) and Shell on its similar offshore Shearwater CCS projects a decade ago, and compared to the dedicated £1bn budget scrapped in November 2015.

Nonetheless Oil & Gas UK welcomed the government’s commitment to technology in the strategy, especially with regards to CCUS, and seeing how such technologies can further reduce UK emissions.

No LNG trucks or ferries

There’s an apparent blind spot in the CGS report when it comes to transport.

Whereas in other countries’ strategic reviews on cutting emissions, LNG as a marine and heavy truck fuel is emphasised as a cleaner fuel than diesel or petrol, and whereas France’s energy strategy put particular emphasis on how natural gas might be a cleaner alternative to petrol and diesel, when sales of new cars using both those fuels are scrapped there – and in the UK – by 2040, here in the UK’s CGS report the only mention of gas in the whole 10-page section about transport is of ‘biogas’.

The report cites how an obligation to include biofuels in diesel and petrol has “stimulated £1bn of investment in UK production facilities” including Argent Energy’s £75mn unit that turns sewage into biodiesel.

And there’s no mention in the report either of two new LNG-fuelled ferries entering service 2018 in Scotland, nor of zero-particulate LNG-fuelled car carriers already taking UK-made cars to Europe (NGW Vol 2, No.19, pp18-21). The first of the two LNG ferries, MV Glen Sannox, is due to be launched into the water November 21, but will need to be fitted out internally prior to its deployment.

UK firm Calor Gas – which in 2014 acquired Chive Fuels, the leading distributor of LNG as a truck fuel – predicts that an increasing proportion of the 120,000 heavy goods vehicles (HGVs) on UK roads will be fuelled by gas over the coming years, partly as concerns grow about air pollution from diesel engines. "This presents a valuable opportunity for LNG, while also offering a solution that’s in keeping with the government’s lower carbon commitments, as outlined in the Clean Growth Strategy," says Calor, welcoming the report.

Calor points out that the UK’s HGVs are responsible for around 27% of roadside nitrogen dioxide (NOx) and therefore "have a key role to play in reducing air pollution". It says that conclusion is backed up with research from Public Health England, the Royal College of Physicians, and the think-tank Policy Exchange with the latter's report citing wider use of gas-based fuels as one of the few viable options available to rapidly improve air quality.

Calculations have shown, says Calor, that if 48,000 HGVs were to be fuelled by LNG instead of diesel, it could cut carbon emissions by more than a million metric tons, helping the UK towards the decarbonisation ambitions covered in the CGS report. The company says it can help, as operator of the largest, publicly-accessible LNG refuelling network in the UK with seven sites, with plans to roll out more refuelling stations. It is also investigating sources of liquefied biomethane for this sector, which would further help contribute towards the carbon targets identified in the UK’s CGS.

Calor, owned by Dutch group SHV Energy, is also a partner in the CaledoniaLNG project (alongside ExxonMobil and others) that aims to develop marine LNG bunkering terminals in Scotland, northern England and the North Sea area, and especially ensure the fuel can be delivered economically to future hubs such as the Orkney Islands and other strategic locations around Scotland. In that respect, though, other firms like Shell/Gasnor are looking to develop UK LNG bunkering, while across the North Sea, Skangas, Engie and Nauticor have made considerable headway with LNG bunkering.

'We'll cover gas in a future report': ministry

Asked about the absence of reference to gas as a future transport fuel, a Beis spokesperson responded: “Natural gas will continue to contribute a significant part of our energy requirements over the next 30 years and beyond. It will continue to play an important role in our energy system as we move towards a low carbon economy. As the cleanest combustion fossil fuel, natural gas can act as a bridge while we develop lower carbon alternatives.”

“The Department for Transport is gathering evidence on the energy sources that are currently in use or might be used in future to power transport, and analysing these data to develop a coherent picture of their environmental, economic and social impacts to 2050,” she added: “Energy sources being considered include petrol, diesel, biofuels, liquid petroleum gas (LPG), compressed natural gas, liquefied natural gas (LNG), hydrogen and electricity. The government will set out further detail on a long-term strategy for the UK's transition to zero road vehicle emissions by March 2018.”

Mark Smedley