[NGW Magazine] China's Gas in Green Cities

China’s recent natural gas supply disruptions are slowing its urbanisation story this year, in line with the overall economic slowdown and its national debt-reduction measures.

The world’s biggest population continues to reduce its reliance on coal and is diversifying into renewables and other sources of energy. The October 2017 UN Habitat report on Sustainable Urbanisation in the Paris Agreement reported that 164 countries submitted nationally determined contributions (NDC), and the focus of China’s was on the contribution that cities could make.

Measures it put forward included the acceleration of the green or low-carbon transformation of industrial areas and mining towns; the development of green public transport; and more carbon storage.

The green and low-carbon transformation of these categories of the economy is evidenced by billion-dollar projects in the provinces, including LNG infrastructure such as regasification terminals, storage tanks, LNG tanker logistics bases and distribution and refuelling stations.

These projects, whether funded by private or public sources, have a target ratio for coal to gas – key performance indicators which these large infrastructure projects hope to achieve. While most of the major infrastructure projects related to LNG are in coastal cities, they are linked to distribution networks inland, which are expanding.

But while gas supply in the residential, district heating and commercial sector has taken priority in China’s clean energy drive, reports kept coming even late last year of coal-fired power plants being switched off before the natural gas pipelines were in place, indicating a gap between the reality and central planners' dreams.

The environmental and economic benefits which could have been derived in these areas of gas demand have suffered a setback, along with China’s urbanisation. However, the trend is still looking good. In 2016, China was home to 6 mega-cities with 10mn or more inhabitants, with Chengdu set to join them by 2030, according to the UN's World Cities Report 2016. In general, the fastest growing were China's coastal cities.

The country is also shifting its economic structure towards less energy-intensive, more value-added services and to emerging sectors of “innovative growth.”

Green Urbanisation

On January 1, China’s environmental protection tax took effect and it is expected to help establish a “green” financial and taxation system that will help limit pollution. An estimated $7.68bn could flow into state coffers following the new tax, according to estimates from analysts quoted in media.

The mandatory tax regime will allocate revenue to local governments as an incentive to combat pollution, and spur on clean energy and gas distribution projects. And so it reinforces the regional governments’ role in the green urbanisation trend.

This will lead to reforms which can succeed only with good regulations able to be reinforced. Local governments will be expected to drive innovation, using the tax revenue to finance multi-year energy efficiency policies and programmes.

Viewed from another perspective, the environmental tax is the first layer of a new governance system, and is unlikely to be of the most benefit to the environment until it has been extended to other polluting sectors such as agriculture and wastewater treatment systems.

Eventually it could serve to widen the rural-urban divide. However the gradual development of a green taxation scheme is part of China’s green urbanisation.

To the Chinese consumer, the switch from coal to gas implies an increase of urban services including natural gas piped to households across China. For those who had to face an abrupt change of provision of urban services, the higher cost of relying on electricity temporarily is not to be dismissed.

The increasing disparity in the affordable cost of living between Chinese cities with clean gas access, versus cities who have no such access is more pronounced.

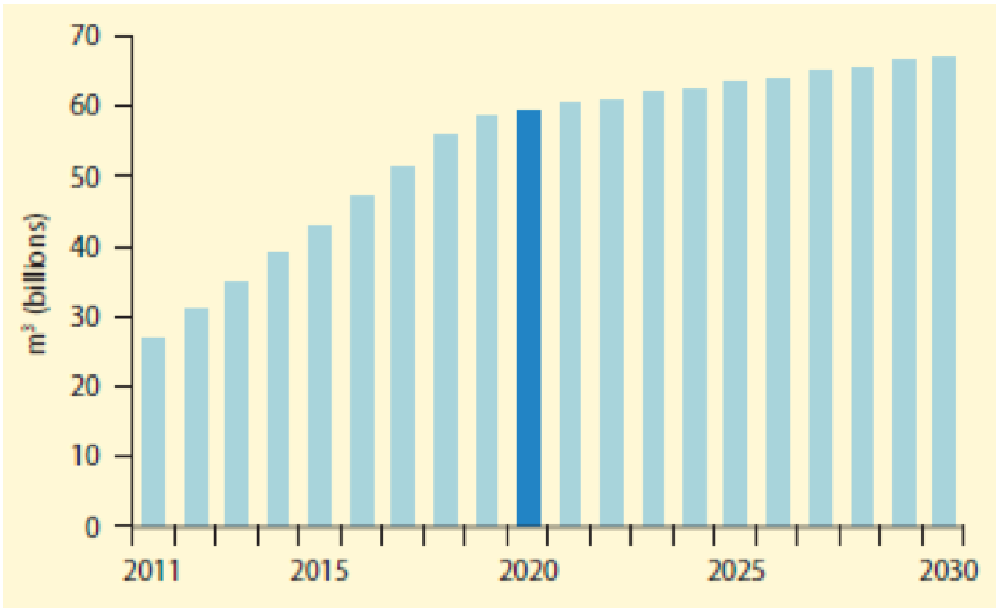

According to the World Bank 2014 Report on Urban China, if it became a top priority for residential consumers to have universal access to pipeline gas for urban households then the gas supply would have to increase from around 30bn m³ in 2011 to nearly 70bn m³ in 2030.

Another 75bn m³ would be needed to shift about 65% of district heating to gas, dramatically reducing the use of coal for this purpose in northern China.

As a result, the Chinese urban population served by piped gas is also projected to increase, from around 500mn in 2013, to 850mn in 2020 and to 960mn in 2030.

The total investment needed between 2014 and 2030 is estimated at yuan 154bn ($24bn), including yuan 16bn/yr between 2014 and 2020. Included in this sum is also the investment required for the switch from liquid petroleum gas to natural gas.

Supply of pipes gas to urban households needed to achieve universal access to piped gas by 2020

Source: World Bank Report on Urban China, 2014

China's industrial gas consumers are grappling with pricing schemes and potential tariffs for larger wholesale distribution networks. The complexity comes even as new players enter the gas supply market, enabling competitive pricing and additional choice.

It requires capital investment in distribution networks and storage for peak demand seasons. At the same time, China is anticipating its next step of green urbanisation: work on its carbon emission trading system (ETS) will start off this year and be completed by 2020. This will allow businesses to raise their energy efficiency.

In October 2011, the National Reform Development Council named five cities – Beijing, Chongqing, Shanghai, Shenzhen and Tianjin – and the provinces of Guangdong and Hubei to establish ETS pilot programs. In a way this wave identifies the greener cities initially and equips them with the incentives and regulations needed to make the surrounding cities greener.

The NDRC basic guidelines require the sub-national pilot cities to set an emissions cap; an allowance allocation methodology; a monitoring, reporting and verification system; an emissions registry for allowances; Chinese Certified Emission Reductions (CCERs) trades; and an emissions trading platform.

The pilot programs have enabled the Chinese government to accumulate at least a decade’s worth of emission trading experience.

The International Emissions Trading Association noted that China will continue to face three main carbon challenges with Chinese characteristics. They are overlapping policies; the emission costs distorted by China’s heavily regulated electricity sector; and the difficulty of defining the emissions cap.

Next steps

Urbanisation is a significant factor for China’s efficient shift towards other sources of energy, besides gas or coal. While it is a precedent for gas supply inland China, it is also an indicator of the rate of urbanisation. This requires more capital invested in green schemes. Using existing modes of governance and raising the efficiency of existing gas pipeline network are important.

At the same time, while there is an increase in green capital investment and debt capacity, China has to balance debt with its urban energy strategy.

Even as the climate-related bond financing indicates support for China’s urban population, there is a gap between China's and the international standards of carbon pricing. Also the qualifying standards for green bond financing are lower than elsewhere.

The lack of consensus-driven accountability will remain a significant reason for the time lag and the amount of actual foreign capital invested in the environment and the climate change business.

NGW