[NGW Magazine] Stopping Methane Leakage

With expectations that natural gas demand will grow in the future, the focus now is on stopping emissions so that its opponents have fewer grounds to object to the relatively clean fuel.

As gas replaces coal and its use grows in other applications such as chemicals, plastics and fertilisers, stopping methane emissions has come to the top of the energy industry’s list of priorities. At least that is the view expounded by the International Energy Agency (IEA) in its World Energy Outlook 2017 (WEO 2017).

Methane is a potent greenhouse gas (GHG), with roughly 30 times more greenhouse warming potential than carbon dioxide over a 100-yr timeframe. It is estimated that the concentration of methane in the atmosphere is about 2.5 times greater than pre-industrial levels. However, the IEA states that estimating methane emissions is subject to a high degree of uncertainty.

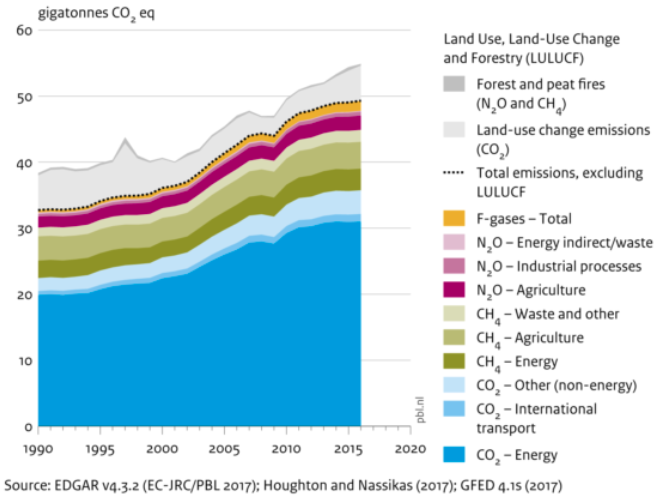

Based on 2016 data from the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre, a report issued by PBL Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency estimated that total global GHG emissions in 2016 were 55 metric gigatons in CO2 equivalent, including land use and forestry (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Global greenhouse gas emissions 1990 to 2016

Source: PBL Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency

Methane emissions amounted to about 17% of this total, with the majority coming from agriculture, wetlands and waste, with 6% attributed to energy activities. In comparison, energy related carbon dioxide emissions were about 52%.

Even though eliminating all energy-related methane emissions would have reduced global GHG emissions in 2016 only by about 6%, nevertheless, because of its high potency, it is considered to be an important contribution in the fight to reduce GHG emissions. The IEA states in WEO 2017 that about 40% to 50% of energy-related methane emissions can actually be abated at zero net cost.

Impact on the oil and gas sector

Methane is the primary component of natural gas, and increasing gas production, including the shale boom in the US, has given rise to increasing methane emissions over the last 15 years. Methane is emitted during the production and transport of all fossil fuels, including oil and coal, but the greatest contribution comes from natural gas.

The IEA stated in WEO 2017 that methane emissions along the gas value chain are potentially at a scale that they could negate some of the climate advantages claimed by using gas. Natural gas emits about 40% less carbon dioxide in comparison to coal, when burnt to generate electricity, and hardly any sulphur dioxide or particulate matter.

The IEA concluded that gas has far fewer GHG emissions than coal when generating heat or electricity, even taking methane leakage into account. But it nevertheless recommended that there is a compelling case for further action to cut methane leakage, pointing out that this would often have financial benefits too.

As it rightly points out, the environmental case for gas does not just depend on beating the emissions performance of coal, but also in ensuring that its emission intensity is as low as practicable.

The main technical challenge facing all efforts to tackle methane emissions is how to detect and measure them in a comprehensive and cost-effective manner. Many researchers have tried to quantify methane leakage, especially in the US where the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has been producing estimates since the 1990s and has accumulated a large volume of data in its Inventory of US Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Sinks.

This annual report provides comprehensive accounting of total GHG emissions for all man-made sources in the US. However, there is an ongoing debate about the accuracy of these measurements. But at least EPA is making them – other countries are far behind.

The actual abatement technologies that can prevent emissions are reasonably well-known, but the challenge is to incentivise their deployment through voluntary or regulatory means. In many cases the saved gas pays quickly for the installation of equipment or the implementation of new operating procedures.

The IEA points out in WEO 2017 that either most of the low-hanging abatement fruit has now been picked or there has been a slowdown in the number of operators choosing to take voluntary emissions reduction action. This raises the question of whether voluntary efforts have reached a point of diminishing returns and whether further emissions reductions may therefore require regulatory intervention.

However, increased attention to methane emissions has led to the setting up of a number of national and international partnerships to tackle such emissions. The ‘ONE Future’ initiative in the US, with participation by ten US-based natural gas companies, aims to achieve an average rate of methane emissions across the entire natural gas value chain that is 1% or less of total natural gas production.

The latest voluntary initiative was launched in the US on at the start of this year by the American Petroleum Institute, called the ‘Environmental Partnership’ and its members are companies producing oil and gas in the US.

This group of 26 accounts for a quarter of all US natural gas production and aims to cut leaks from wells, pipelines and other sources from US onshore production. Under the initiative participating companies commit to implement leak monitoring using the latest detection methods, replace or retrofit highly emitting pneumatic controllers and attempt to minimize emissions from manual liquids unloading for gas production sources. Erik Milito, API’s director of upstream and industry operations, said that this group is in favour of cost-effective rules.

Many of these initiatives are focused on the US, because of its fast-increasing oil and gas production, especially shale; but an increasing number have an international dimension.

Oil majors pledge

This international dimension includes eight oil majors that have realised that their drive to promote natural gas as the fuel of the future, requires addressing the methane issue. This is seen as crucial to address negative public perceptions about the impact of such emissions on the global climate and thus gain public acceptability of the use of natural gas well into the future.

This includes ExxonMobil, Shell, BP, Total, Eni, Statoil, Repsol and Wintershall. They came together in November 2017 and pledged to reduce methane emissions and are co-operating to address climate change. In order to achieve this they adopted five 'Guiding Principles'. These are:

- to continually reduce methane emissions through a variety of means

- to push for improvements through the sector, including pipelines and power plants

- to improve the accuracy of emissions data

- to push for sound policies and regulations that reduce emissions without eliminating gas production

- to increase public transparency.

This initiative highlights a growing recognition within the energy industry that it must tackle methane leakage if it is to secure a future role for natural gas.

The companies that signed these principles are aware that they must recruit new members and expand the initiative across the whole of the industry. The head of the UN Environment, Energy and Climate Branch, Mark Radka, said: “The Guiding Principles provide an excellent framework for doing so across the entire natural gas value chain, particularly if they’re linked to reporting on the emissions reductions achieved.”

IEA’s Tim Gould, who helped develop the guidelines with industry, said that “credible action to minimise methane emissions” was “essential to the achievement of global climate goals, and to the outlook for natural gas”.

As the IEA pointed out in WEO 2017, a future role for gas not only requires it to be affordable relative to other fuels and technologies, but also depends on the industry demonstrating credibly that methane emissions from oil and gas operations are being minimised.

The initiative members stated that the Guiding Principles are “complementary to and mutually reinforcing of other initiatives, including the Oil and Gas Climate Initiative and the Climate and Clean Air Coalition’s Oil & Gas Methane Partnership.”

ExxonMobil had launched its own plan to cut leaks in September 2017. Welcoming the new initiative, Darren Woods, ExxonMobil’s CEO, said and “we are pleased to see other companies joining us in our efforts.” The company is also implementing an enhanced leak detection and repair program across its production and midstream sites, while also evaluating opportunities to upgrade facilities to improve operational efficiencies and reduce methane emissions.

Shell is also taking steps toward addressing methane emissions. In August 2017, it announced a new technology trial at a well-site in Alberta, Canada, where it is piloting a specially designed laser to continuously monitor emissions of methane (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Trial of laser-based technology to monitor methane emissions

Source: Shell

The move by Shell is part of a growing gas industry interest in smart, sensor-based methane detection technology. Statoil is running a similar field test in Texas and so is PG&E in California.

Behind these demonstration projects is a collaborative initiative, the Methane Detectors Challenge, begun by the US-based Environmental Defense Fund (EDF) four years ago.

As EDF points out, each of these projects is promising, but the ultimate test will be broad-scale adoption of innovations that generate further methane reductions.

US methane emission cuts

The IEA says that recent studies have greatly improved the state of knowledge of methane emission levels in the US, where emissions have been analysed more fully for longer than those in other countries, using extensive measurements.

Based on the latest data from the EPA Greenhouse Gas Reporting Program, methane emissions from the most productive shale basins in the country have fallen considerably in the past six years, (Figure 3). These reductions have been achieved even as oil and natural gas production increased 54% and 16% respectively.

Figure 3: Methane emission reductions in top US gas producing basins

Source: US EPA

Over this period, the total emission reduction in the 8 basins shown in Figure 3 was over a fifth. The EPA concluded: “The decrease in production [methane] emissions is due to increased voluntary reductions, from activities such as replacing high bleed pneumatic devices, regulatory reductions, and the increased use of plunger lifts for liquids unloading.”

EPA data actually shows that natural gas emission intensity has been halved in the US over the past 25 years. But even in the US more needs to be done to measure methane emission levels more accurately, disclose them and to tackle such emissions more effectively. The Methane Detectors Challenge is a step in the right direction – more is needed.

Impact of abatement

The following is based on IEA studies reported in WEO 2017, related to the ‘New Policies Scenario’. This scenario incorporates the Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) made for the Paris Agreement, supplemented or superseded by more recent country announcements.

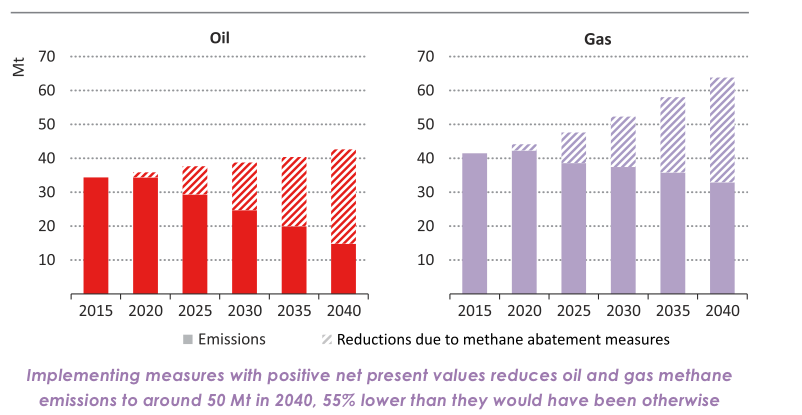

Without explicit efforts to reduce emissions, the IEA states that combined oil and gas related methane emissions would rise to over 105 mn tonnes (Mt) in 2040.

However the proportion of total methane emissions that could be reduced using abatement measures that result in overall cost savings or have no net cost could reach 60%, reducing emissions down to less than 50 mn tonnes in 2040.

The IEA estimates that this would reduce the temperature rise in 2100 by 0.07 degrees C compared with the trajectory that has no explicit reductions.

While this may not sound like a large difference, in climate terms it is important. The IEA estimates that to yield the same reduction in the temperature rise in 2100 would require reducing CO2 emissions by 160bn mt over the remainder of the century. This is a huge level of reduction, broadly equivalent to the CO2 emissions saved by immediately shutting down all existing coal-fired power plants in China.

Implementing additional measures to limit the average global surface temperature rise in 2100 to 2 degrees Celsius, can reduce methane emissions further, down to less than 20mn tonnes in 2040.

In order to achieve such reductions oil and gas operations need ultimately to accomplish two goals: measurement and abate. Measurement is critical in assessing the efficacy of policy actions and in assuring the public that the issue is being addressed. The IEA states that alongside voluntary efforts, policy and regulation will be central to achieving this.

In addition to the environmental impact, doing nothing costs money. As Figure 4 shows, 76mn mt/yr of methane are being lost, close to the gas produced by Norway. At today’s gas prices this is equivalent to $34bn. This would more than pay for implementing the required emission abatement measures.

Figure 4: Oil- and gas-related methane emissions in IEA’s New Policies Scenario with (solid) and without (dashed) abatement measures

Source: IEA WEO2017, Fig 10.13

Implications

The role that natural gas can play in the future of global energy is closely linked to its ability to help address environmental problems. With concerns about air quality and climate change looming large, natural gas offers many potential benefits if it displaces more polluting fuels, such as coal, but it needs to get into grips with methane emissions.

For these reasons, as EDF points out, methane is a problem that has caught the attention of regulators, investors and consumers alike.

Many environmental campaigners argue that the pollution caused by gas production, and the investment in long-lived gas infrastructure that will continue emissions, even if at a lower rate than coal, mean the climate argument for increasing the use of gas is unconvincing.

On the other hand, gas is a modest contributor to methane emissions when compared to all other sectors, including agriculture. And although methane is a powerful greenhouse gas, its lifespan is much shorter than CO2. Efforts to control methane emissions should be part of broader action to reduce such emissions, including agriculture. After all, out of the 17% methane emissions shown in Figure 1, only about a third came from energy.

Unquestionably, more must be done to address methane in the energy sector and understand its impact. Harmonising measurements and calculation methodologies across the industry, for example, should make it easier to assess the problem and produce solutions for methane abatement and even commercial use. The energy industry understands this and is taking pro-active approaches to tackle the problem.

In this respect, recent commitments from the oil majors to tackle the problem are welcome. But relying on the industry to regulate itself may not be sufficient. As the IEA pointed out, a sound regulatory framework may be needed to take methane emission abatement further forward.

The European Parliament voted in December 2017 in favour of a draft governance regulation for the Energy Union, which could oblige EU member countries to report on methane emissions to the European Commission every two years. This may be a step in the right direction.

Charles Ellinas