[NGW Magazine] Canadian Methanol Faces Competition

Entertaining only modest hopes for exporting large amounts of LNG, western Canadian gas producers are seeking any and all marketing prospects for their gas now that their historic key gas customer – the US – is their biggest competitor.

One of the markets that Canadian gas producers are considering for their locked-in gas is the petrochemical industry. But tax changes in the US – following US president Donald Trump's 'America First' principle – mean that even this option is losing its lustre.

Canada has developed a strong manufacturing cluster – Alberta’s Industrial Heartland – just outside Edmonton. Other North American petrochemical clusters are to be found in the US Gulf Coast region, and in the Canadian province of Ontario, while a fourth cluster may be emerging in the US northeast, where Anglo-Dutch major Shell is developing an ethane cracker and three polyethylene units in Pennsylvania that will produce 1.6mn metric tons/year. Feedstock will be drawn from the Marcellus and Utica shale gas fields.

All four clusters are based on natural gas liquids feedstocks like ethane, propane and butane, but there remains a largely untapped market based on methane feedstock, according to a recent report by the Canadian Energy Research Institute (CERI) that examines the challenges and opportunities of a methane-based petrochemical industry.

“The growth of methane derivative products will be driven by a combination of factors in the future,” the study says. “Key among them is the availability of cheap natural gas feedstock. In Canada, the decline in Canadian natural gas exports from western Canada to the US and the availability of eastern US natural gas for import to Ontario provide abundant commodity options for petrochemical companies. While the demand for natural gas liquids in petrochemical operations has always been strong, additional markets need to be explored for the leftover natural gas – methane.”

Canadian natural gas production, CERI says, is expected to reach 21bn ft³/day by 2037, while Marcellus production is forecast to reach 30bn ft³/day by the mid-2020s, displacing traditional eastern Canadian and northeastern US markets for western Canadian gas and underpinning development of Pennsylvania’s petrochemical cluster.

Once the liquids like ethane, propane and butane have been stripped from natural gas, 92% of the remaining stream is methane and the development of one world-scale methanol manufacturing plant would require about 150mn ft³/day of natural gas, while an ammonia plant would consume more than 600mn ft³/day.

Currently, Canada's only methanol production comes from a 600,000 mt/yr plant in Medicine Hat, operated by Vancouver-based Methanex. Methanex also has methanol production facilities in Louisiana, Trinidad, Chile, New Zealand and Egypt.

But with low growth rates forecast for ammonia and urea production, CERI’s study suggests Canada’s best options lie in the development of methanol or formaldehyde facilities.

“The growth rate for methanol products is quite high – in the range of 3% to 4% – so this is where we want to look for a sweet spot where there is significant growth and where the competitiveness of those activities in Canada makes a difference,” CERI CEO Allan Fogwill told a Calgary seminar in April outlining the results of the study.

Among nine methane-derivative facilities studied, CERI’s “sweet spots” were found in three: methanol; Fischer-Tropsch Synthesis (FTS, also known as gas-to-liquids, a technology which converts syngas derived from coal, natural gas or biomass into very clean-burning transportation fuels as well as petrochemical products); and hydrogen. Internal rates of return (IRRs) for all three lie in the 15% to 20% range, Fogwill said, suggesting the development of any of these facilities would be economic under current market and commodity price conditions.

And any of the three, he added, would have a material impact on both the provincial and national economies: a new methanol plant in Alberta, for example, would add nearly $300mn to that province’s gross domestic product (GDP) and boost Canada’s GDP by $345mn; while the development of an FTS facility would add $365mn to Alberta’s GDP and $425mn to Canada’s.

More than 9,000 person-years of employment would be created in Alberta by an FTS plant, while a methanol plant would bring nearly 7,500 person-years of new employment, the CERI study showed.

But even with these positive economic underpinnings, Fogwill cautioned that North American petrochemical manufacturers need also to be aware of what is happening elsewhere – especially in China, where new government policies aimed at climate change could bring new challenges.

“In North America we are seeing growing demand for ethylene, and methanol is on the cusp of significant expansion in Canada and the US, in large part because natural gas is cheap,” he said.

“Coal to olefins is a major push that the Chinese are moving forward with, because they’ve got lots of coal and very little natural gas and they’re moving away from coal for power generation. With that move, the cost of coal in China becomes practically zero.

“We need to pay attention to what is happening there because that is a significant market for North American petrochemicals. If they are going to move heavily to coal to olefins, that becomes a threat.”

While CERI’s initial study showed that natural gas to methanol opportunities were essentially even in any of the three major North American clusters – Alberta, Ontario and the US Gulf Coast – Fogwill said the balance dramatically shifted in favour of the Gulf Coast when the US president, Donald Trump, brought in his new corporate tax changes late last year.

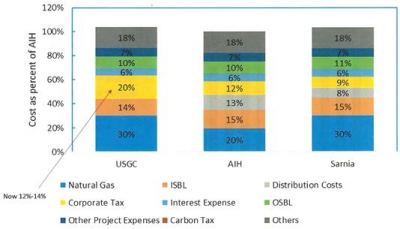

Methanol: Life Cycle Costs Make-up

Credit: Canadian Energy Research Institute (CERI)

With the changes, the US corporation income tax rate fell to 21% from 35%, while the depreciation rate changed from straight line to accelerated depreciation levels that can allow 100% capital cost recovery in the first year of operation.

“When we first did this analysis, before the US tax code changes, [Alberta] had this advantage from a corporate tax point of view compared to the US Gulf Coast,” Fogwill said. “That has gone now.”

Before the tax code changes, CERI’s study noted, corporation tax played a significant role in improving Canada’s industrial competitiveness versus the US. For example, the contribution [of corporation taxes] to the life-cycle costs of a US Gulf Coast plant would have been twice those in either Alberta or Ontario. “Prior to those tax changes, 20% of the life cycle costs of a [US] project was corporation taxes, versus 12% in Alberta and 9% in Ontario,” Fogwill said. “With the tax code change in December, the corporation tax portion of the life cycle cost was reduced to between 12% and 14% – it makes a huge difference.”

Alberta still enjoys a considerable advantage over both the Gulf Coast and Ontario in terms of natural gas feedstock costs, at 20% of life cycle costs versus 30% in both of the other jurisdictions. But Alberta faces a major challenge that is absent in both Ontario and the Gulf Coast: the logistics of moving product to distant markets.

“If you move a liquid or a solid you are going to be moving them by rail, and CN and CP [Canada’s two national railways] are already having trouble moving grain,” Fogwill said. “That adds to the challenge of putting something especially in Alberta, because in Ontario you can still rely on Great Lakes freighters to move the product to market. In Alberta, the logistical challenge is significant and companies are going to be watching that quite closely to see if they are going to be willing to invest in a multi-billion-dollar project in Alberta when things can’t get to market.”

Dale Lunan