[NGW Magazine] A trying time for the upstream

The upstream industry must defend itself in a number of European courts against litigants who seek to limit its activities on various grounds: some may even succeed, but in any case the coincidence of the cases is startling.

In November, court hearings began in Oslo on whether the government was right to award Arctic offshore acreage to oil and gas explorers in 2016, while also an important ruling was handed down by the Netherlands’ highest court over a production cap imposed on the giant Groningen gas field. A UK ruling is expected shortly relating over a far-ranging injunction applied to shale gas protesters.

In one area perhaps, citizens’ groups have become more emboldened than in the past to challenge producers, and often on divergent matters. In the Netherlands, it’s about the safety of continuing to produce gas, when even the government admits that this has produced earth tremors in the past. In Norway, it’s over a range of issues ranging from the public purse to the future of the planet. As gas production in Europe declines, could what little is left become more litigious?

Is there common cause to be found in such disputes? Dutch producer NAM says there can be, but its view may not be widely shared.

From the Arctic...

Court hearings are taking place at Oslo District Court from November 14 through 23 about the validity of the June 10 2016 decision by Norway’s petroleum ministry on its 23rd licensing round.

That decision awarded Statoil operatorship of four licences; Lundin, three; and Centrica, Det Norske, and Cairn Energy one each – for a total of ten licences spanning 40 blocks, all in Norway’s part of the Barents Sea and inside the Arctic Circle.

Greenpeace Nordic Association and another non-governmental organisation Natur og Ungdom (Nature and Youth) are suing the petroleum ministry. The two plaintiffs claim that the decision is invalid as it contravenes section 112 of Norway’s constitution, which prohibits decisions that may have an adverse effect on the environment or climate; and also the Paris climate change accord.

Environmentalists and fishing folk believe the Barents Sea is too sensitive for petroleum exploration, as it takes far longer for the ecology to recover from oil spills in the Arctic than further south.

Greenpeace Nordic also contends that new Arctic licences should not be issued, as the world already has more oil and gas reserves than it can safely consume if keeping to UN climate action targets. It argues that development of the ten Round 23 licences may also breach future Norwegian CO2 limits.

The state’s view is that the decision on the 23rd licensing round is valid and that the decision was made following extensive professional, administrative and political processes, which are in line with the requirements of the constitution and other legislation. The ministry argues that the 23rd round was approved in parliament, though notes a proposal is being debated to halt the ongoing 24th round.

Both it and the court tell NGW that the Oslo hearings will be completed on November 23. Greenpeace Nordic expects it then will be a further four to 12 weeks before a verdict is given.

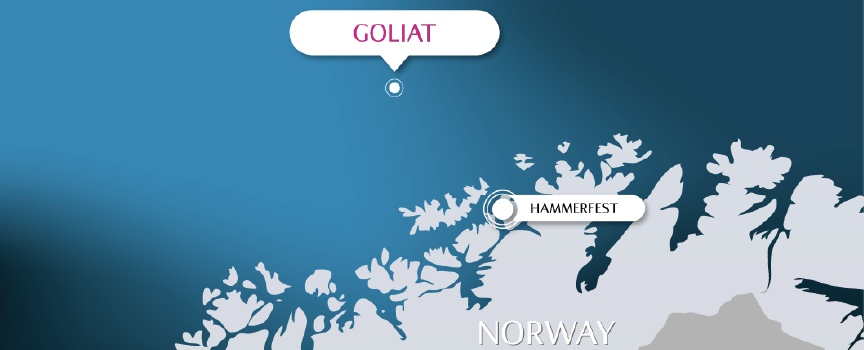

Away from the court, the ethics of producing so far north, coupled to safety issues at the Eni-operated Goliat oil field this year and last, have meanwhile put the petroleum ministry on the defensive.

Map credit: Statoil

The petroleum ministry issued a statement November 14 after it received a parliamentary question about ‘when the Goliat field would be profitable’. It replied that Eni first stated that total revenue would exceed total investment and operating costs in 2019/2020 – which was later corrected by the company until 2022 – and immediately conveyed to parliament.

The ministry acknowledged it does not calculate tax-take figures by field area, as companies are taxed across the Norwegian continental shelf. But it said it has become aware of a 2015 internal memo by upstream regulator NPD about the profitability of Goliat development, based on Eni’s updated cost estimates and production profiles at that time. “The NPD note showed that it is very profitable to get into production as soon as possible. With the assumptions used by the directorate, the note summarised Goliat as marginally profitable or marginally unprofitable, depending on whether associated gas exports start [from the field] in 2030.”

Goliat began oil production March 12. 2016 but had to stop several times, including an entire month from late August to late September this year, owing to safety problems.

Greenpeace thinks that admission of doubt over whether Goliat will be net-profitable, once tax concessions are included, backs up its case: “The Goliat project is proof in itself how challenging Arctic oil drilling is. Even though its remoteness is not as great as many of the oil licences in the 23th licencing round, operator Eni has had several serious safety issues and the profitability is seriously questioned. We think as a result of this that its operatorship should be withdrawn. What was meant to be the oil industries’ first step into Norwegian Arctic waters is now a symbol of failure for the industry. It’s clear they are not up to the challenges of Arctic oil drilling,” it said.

Eni as operator of the field (65%) and its partner Statoil (35%) beg to differ. So too do Norway’s offshore labour unions: earlier this month they said Eni should not be stripped of Goliat operatorship; that Eni Norge’s management has improved; and that the focus should stay on safety rather than switching operators. A former Lasmo manager, Philip Hemmens, was brought in to head Eni Norge last year.

... to the Lowlands

As hearings got underway in Oslo, the highest commercial court in the Netherlands on November 15 delivered its judgement on production from the giant Groningen gas field.

In short, the Dutch court ruling said that production, which is operated by Shell and ExxonMobil joint venture NAM, will remain at 21.6bn m³/yr until the relevant minister takes that decision.

The ruling, by the administrative jurisdiction division of the Council of State (Raad van State), also said the minister of economic affairs and climate “failed to properly substantiate his previous decision to allow 21.6bn m³ to be extracted per gas year over the next five years” and set the parameters whereby the minister should take another decision within the next 12 months.

The court was referencing a May 2017 decision by former economy minister Henk Kamp that the annual Groningen gas production cap of 24bn m³/yr previously set from October 2016 until September 2021 be reduced by 10%. Eric Wiebes replaced Kamp as economic affairs and climate (EZK) minister last month._f300x300_1511331731.jpg)

The November 15 ruling says that Kamp based his decisions on the impossibility of assessing the risks of gas extraction for people in the earthquake zone – but that he failed to convince judges of the accuracy of his position. The minister should in any event have studied the options for mapping out the risks in greater depth, or better explained why he consented to the 21.6bn m³/yr extraction level without such a study. The court said it was “unacceptable” that the minister determined gas extraction for five years, without having assessed the attendant risks. If it was indeed impossible to assess the risks, “the minister could at least have been expected to examine and explain how the safety interests of the individuals in the earthquake zone would otherwise be considered in the decision-making.

“Neither has he adequately explained why security of supply has been taken as the lower limit for the volume of gas to be extracted, despite uncertainty about the consequences. Furthermore, he has failed to make clear potential measures to limit the demand for gas. The minister is granted a year to reach a new, better substantiated decision,” added a statement from the court.

Although the court set aside both Kamp’s September 2016 decision (setting 24bn m³/yr as a cap for five years) and his amendment (reducing that to 21.6bn m³/yr), it decided against allowing unlimited production by NAM as that would leave objectors in an even worse position – something the court said would have been “unacceptable.”

Around 20 objectors appealed against both Kamp’s decisions, including local activist group Groninger Bodem Beweging (GBB), individual citizens, the Groningen provincial executive, and various municipalities in the Groningen province of northern Netherlands.

And so the court set an ‘interim provision’ as a temporary measure, enabling NAM to produce in line with the most recent amendment decision, namely at 21.6bn m³/yr, saying this “will remain in force until the minister’s new gas extraction decision comes into effect.”

An EKZ ministry spokesman told NGW: “The main conclusion is clear: within a year a new decision as to be taken. That’s what we start working on.” The Dutch government has for several years now admitted that quakes in the area are induced by gas production, and Kamp had said his May 2017 amendment was based on fresh information from the state’s mining inspectorate (SodM).

The Groningen field is operated by NAM with a 60% interest, while Dutch state petroleum holding EBN has 40%. This partnership has, in the past, been cited by residents as a factor for the state in the past failing to live up to its obligations as independent regulator – as it knew any reduction in production would lead to a corresponding decline in the state’s tax and royalty revenues.

NAM, which challenged minister Kamp’s May decision in June and by doing so effectively sided with the 20 or so residents’ and local authority groups, said it felt justified by the Council of State’s ruling that it is possible to estimate the risks associated with gas extraction based on calculation models.

“The ruling also indicates that there is insufficient motivation about why the previously established safety framework has been abandoned. We have not taken the step of appealing against a ministerial decision about production before in our 70-year history. The reason was to get clarity. Gas production from the Groningen… requires clear frameworks that justify the importance of safety,” said NAM.

NAM even suggested common cause with other NGO objectors to Kamp’s decision. It cited remarks made July 13 by NAM director Gerard Schotman in a hearing session: “With this appeal, we are on the same side as some of the other appellants. However contradictory it may seem - we have a common interest. That interest is safety. And clarity about that safety.”

The 20-odd objectors that appealed against Kamp’s decisions included local activist group Groninger Bodem Beweging (GBB), individual citizens, the Groningen provincial executive, and various municipalities in the Groningen province of northern Netherlands. GBB expressed delight on Twitter November 15 that the Council of State had “annulled Kamp’s gas production decision” and had thrown wide open the debate about energy security of supply.

Active for at least six years in seeking compensation for buildings damaged by gas production-related quakes and subsidence, GBB may find NAM’s ‘common interest’ remarks puzzling.

Residents find themselves at odds with NAM in a separate ongoing legal action seeking to quantify the level of compensation to be paid for blighted buildings not vacated by residents. Many objector groups have campaigned for a reduction, or even a halt, to Groningen gas production.

A court hearing in Leeuwarden in the northern Netherlands this month heard an appeal by NAM on whether a September 2 ruling in the nearby town of Assen, relating to certain compensation payments to residents with property damaged by gas production-induced earthquakes, should be struck down.

A lawyer representing residents group, Stichting WAG, said the Leeuwarden appeal court will give its verdict on January 23. He added that NAM has also sought an appeal in a case involving certain residents who had filed for compensation for psychological distress caused by the earthquakes and damage. “We are waiting for the papers of the NAM in this appeal,” he said.

Outside the court room, there was a setback last week for those opposed to further gas production in the region. A debate in the Dutch parliament’s legislative chamber (Tweede Kamer) the previous evening November 14, appears not to have gone how activists would have wished.

The debate was whether a new gas discovery offshore northern Netherlands – 20 km north of the island of Schiermonnikoog – should be authorised for development. The conclusion of the debate, and the view expressed by EZK minister Wiebes, was there was no reason to block its development.

The gas discovery was announced late September by UK-based Hansa Hydrocarbons, together with Dutch partners Oranje-Nassau Energie (ONE) and the state holding EBN, when a vertical drill stem test achieved a maximum of 53mn ft³/d, the limit of surface equipment. Hansa though says the discovery extends across the Dutch N04, N05, N08 licences and into the German Geldsackplate licence – all offshore. Ruby upstream partners put its reserves at 6bn m³, according to press reports.

That’s far less than the supergiant Groningen field whose initial recoverable reserves when discovered in 1959 and started up in 1963 were put at 2.9 trillion m³ – of which two thirds had been produced by 2015. When the 50th anniversary of Groningen’s discovery was celebrated in 2009, Exxon and Shell said the field was good for another 50 years.

But the mood over production has changed significantly since – and it’s hard not to conclude that the asset was simply pushed too hard in 2013, when Groningen output was ramped to 54bn m³ – not its highest annual production level, but certainly the highest for many years. The interim cap of 21.6bn m³/yr now allowed is just 40% of that 2013 output, and owners are increasingly wary of any forward production profile for the field.

And the UK Midlands

Any gas found in the Barents Sea, plus the known deposits in the northern Netherlands, are seen as conventional – in contrast to what is now eyed as the focus for exploration onshore Britain.

In the English High Court, hearings took place from October 31 to November 2 on an application by protesters for a wide-ranging injunction, secured this summer by shale acreage holder Ineos, to be set aside. The ruling in that case is still pending. Ineos and other explorer Cuadrilla want to start using hydraulic fracturation (fracking) to test horizontal wells on their blocks in northern England.

Another UK explorer though, has taken a more softly, softly approach: IGas is fully permitted to undertake vertical test wells in the English east Midlands, but has chosen not to seek permission at this stage for fracking. If it later wants to frack, it will need to apply for a further approval.

So back to the original question: Is producing gas in Europe becoming a much more litigious matter? Gordon Ballard, executive director of the International Association of Oil and Gas Producers (IOGP), told NGW: “I think it’s fair to say so. Legal actions motivated by climate concerns are a relatively new thing.

That’s why it’s more important than ever that we clearly explain to local communities why we don’t compromise on operational and environmental safety. But we also need to address the underlying worry which motivates these actions by explaining that oil and gas are actually compatible with a 2C objective, and how using them in a different way is actually going to help us get there.”

Greenpeace UK Elisabeth Whitebread agrees to a point: “Courtrooms have become the new frontline in the battle against climate change. From the Philippines to Norway and the US, more and more people are taking governments and the fossil fuel industry to court for their role in altering our climate.”

However, she adds: “The fracking industry has already lost its most important case - the one debated in the court of public opinion. The shale gas industry has been banned or has pulled out from one country after another, and public support for fracking in the UK has sunk to an all-time low. Studies have shown there is no role in Europe for new gas, coal, or oil production because of their carbon and methane emissions. Both the public and politicians have started realising fracking is an industry we don’t need, don’t want and can’t afford.”

Norway Central Bank pitches in

As last week drew to a close, another significant move was announced – but not from the courts. Norges Bank, the country’s central bank, published a letter sent to Norway’s finance minister in which it recommends the removal of all oil and gas stocks from the country’s $1 trillion (kroner 8,270bn) rainy-day sovereign wealth fund (Government Pension Fund Global, or GPFG).

Picking up on a theme developed earlier by Oxford economist Dieter Helm, that investors in oil could “harvest and quit”, the bank’s deputy governor Egil Matsen writes: “This advice is based exclusively on financial arguments and analyses of the government’s total oil and gas exposure and does not reflect any particular view of future movements in oil and gas prices or the profitability or sustainability of the oil and gas sector.”

It notes that the government already has a direct investment in Statoil, that is not part of the GPFG.

“It is the bank’s assessment that the government’s wealth can be made less vulnerable to a permanent drop in oil prices if the GPFG is not invested in oil and gas stocks,” noting that roughly 6% (or kroner 300bn) of the GPFG is currently invested in such stocks.

For that reason, the bank’s executive board says that, for its 2017-19 strategy regarding GPFG, it “will adopt a broader wealth perspective when advising the ministry.”

Mark Smedley