[NGW Magazine] Amlo rocks the boat

Key government members of Mexico’s energy industry find themselves in a strange place these days.

Since 2013, they have orchestrated the country’s historic shift in energy policy, secured billions in foreign investment from new entrants, and designed infrastructure projects to strengthen and improve Mexico’s natural gas, fuel and oil security for decades to come.

And as of December 1, it is likely they’ll be out of a job.

While it is common for an incoming government to make sweeping changes, the upcoming transition in Mexico has the makings of a radical shift, particularly in the energy industry. On July 1, Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, a left-leaning populist, won the presidency on promises to reduce poverty and income disparity, weed out corruption, and empower the Mexican people, largely by reducing foreign dependency and creating opportunities at home.

His victory as the Morena party candidate not only meant a shift in direction and rhetoric, but a changing of the old guard in Mexico, where the incumbent Institutional Revolutionary Party, or PRI, had ruled for most of the past century.

One of Lopez Obrador’s priorities is to make radical changes to an energy sector that has been open to international competition and investment for the first time since 1938. Amlo, as the incoming president is known, now has much of the energy industry spooked, as he has vowed to halt oil and natural gas auctions and review the contracts awarded in the current administration for signs of corruption. With a big enough majority in the senate and congress to allow Amlo’s government to implement new legislation with little opposition, the energy sector has much to be concerned about, on the eve of his six-year term.

The president-elect confused the industry by announcing September 6 that his administration would in fact hold oil auctions, contradicting comments made weeks earlier. In fact he meant not the government’s public licensing rounds, but drilling tenders for the state-owned oil company Pemex.

“It’s a little difficult to discuss the change of government because we still don’t know exactly what’s going to happen, so everything is very speculative at this point,” David Madero, head of Mexico’s gas pipeline and storage operator National Natural Gas Control Center (Cenagas) told NGW. “I would hope the new government doesn’t make major modifications to the opening of the market because I think it has been very favourable for all of Mexico.”

Low production, high imports

For members of Mexico’s natural gas industry, the hope is for some semblance of continuity that will ensure the most pressing challenges –falling production, rising dependency on US imports and rising domestic demand – will remain priorities for the new administration. According to David Rosales, general director of natural gas and petrochemicals at the energy secretary (Sener), Mexico consumes about 7.9bn ft3/day of natural gas, of which 5.1bn ft3/day, or 65%, is imported from the US for use in the oil, electricity and industrial sectors.

“In 2019 and 2020, the amount of natural gas imports will increase, without question,” Rosales said in an interview with NGW. “It is unarguable that natural gas continues to be indispensable for the economic growth of Mexico. Imports are going to continue growing in the next two years at least, production is going to continue to decrease and consumption will increase. That has to be filled by imports.”

Rosales said that Sener officials, have held “very productive” talks with members of the incoming administration to plan for the transition. The current Sener directors have presented “where we are, what we’ve done and where we’re going, as well as offered perspectives and alternatives,” on how to continue to develop the natural gas market.

Perhaps the chief concern of the industry is whether Amlo’s team will proceed with plans to auction fields for shale drilling in Mexico’s gas-heavy basins. In early August, Amlo said publicly that he would cancel the country’s first-ever shale auction, planned for February 2019. By doing so, companies would be prohibited from developing basins thought to contain some of the largest unconventional gas resources in the world.

“The majority of the opportunities to increase production are in unconventional basins such as Burgos and in the southern part of the country. But there are other opportunities in conventional basins as well,” Rosales said. “Eagle Ford extends beyond the border in the northern states of Coahuila and Tamaulipas, for example…. If they are allowed for exploration and development, they could potentially kick-start national production.”

US export capacity grows

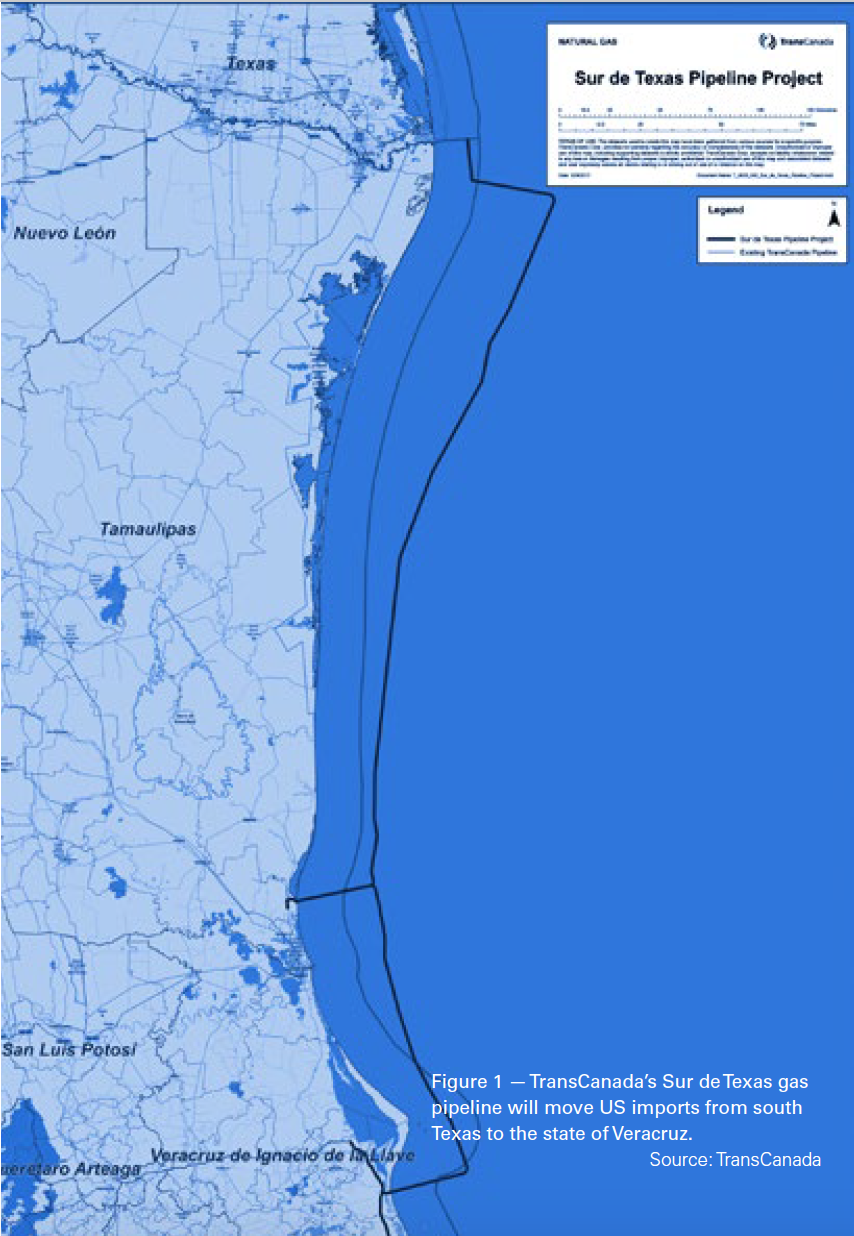

Even if the shale auction is not held in February, both Rosales and Madero say the country’s natural gas network will soon be aided significantly, in terms of price and supply, when the Sur de Texas gas pipeline – a joint venture of TransCanada and Sempra Energy’s Mexican subsidiary, IEnova –comes online in the coming months. The $2.1bn pipeline, which runs 800 km from southern Texas to the Gulf of Mexico port of Tuxpan, has the capacity to supply up to 2.6bn ft3/day, making it the country’s largest gas import line.

Sur de Texas is “maybe the most emblematic project we have in the short-term” and eventually “will drastically reduce imports of liquefied natural gas,” Madero said. “Construction is expected to be completed by the end of this year and operations are expected to begin as soon as early next year or late spring. It will allow for more gas to be sent to the south of the country where supply is limited, allowing for more storage opportunities, particularly in the Yucatan peninsula.”

Imports of LNG from the US are expensive, so an eventual reduction would be an economic boon for Mexico, according to Madero.

IEnova is also looking into the possibility of reconverting its Energia Costa Azul (ECA) regasification terminal and storage plant “into a liquefaction plant that can import gas from the US from the pipelines that are already in place, liquefy it and send it to various other parts of the world, particularly the relevant Asian markets, such as China, Japan and South Korea,” according to Rosales.

Sited on Mexico’s west coast just outside of the Baja California town of Ensenada, “the liquefaction project would add natural gas reception, treatment and liquefaction capabilities and loading of LNG cargos… to create many benefits and provide access to cost-competitive LNG to world-wide partners,” according to the company’s website. “Development of the ECA liquefaction project is contingent on several factors, including but not limited to securing all necessary permits and approvals, completing the required commercial agreements, obtaining financing and reaching a final investment decision.”

Mexico is not presently looking to convert other terminals, such as Manzanillo or Altamira, into export hubs, Rosales said.

Challenges ahead

While the opening of the energy market during the current administration “has made for a very dynamic gas market in Mexico,” as Madero puts it, the challenges facing the incoming government are numerous.

When asked about the most pressing challenges ahead for the natural gas market, Rosales named several.

“The primary challenge I see is: to improve natural gas production,” he said. “Not only for the arguments of the natural gas market, but for the profound need for liquid for petrochemicals such as ethane, propane, ethylene, oxyethylene, ammonia, and several other products where we have deficiencies.”

Madero echoed this thought, saying Mexico and Pemex need to continue to look for opportunities to develop natural gas and to optimise current production, much of which is flared and not processed.

“What is required is production and then processing of natural gas for domestic consumption,” Madero said.

Both also agreed that continued development of Mexico’s natural gas pipeline network, particularly in those parts of the country that are hard to access, will be required to reduce costs, increase supply and mitigate potential shortage risks.

“There is a need to reconnect or strengthen the connection between the south and north of the country,” Rosales said. “The installations we have in the south of the country are designed to carry gas to the Gulf of Mexico, though they aren’t bidirectional. They don’t have the technical conditions to receive gas or send gas the other direction.”

Madero added that, with more pipeline connections and storage options in less populated regions of the country, Mexico could “reduce the vulnerability of the imports” to southern states such as Chiapas, Oaxaca, and Guerrero, as well as west coast states such as Nayarit and Baja California.

This would not require megaprojects, according to Rosales. “With just a limited amount of investment, it could mean far more consumption options throughout the country,” he said. “Imports can be tricky because you depend on another source to provide your needs. With better storage and supply, there is much better security and less risk.”

Rosales also said he feels Mexico needs to transition from a country that consumes LPG to one that consumes more natural gas.

“Mexico has very low penetration of residential consumption of natural gas,” he said. “In Mexico City, for example, we continue to be very reliant on propane and LPG, and that should be substituted for natural gas. There are still many cities across the country where natural gas still doesn’t flow.”

He said Mexico’s reliance on LPG meant that residents are paying more for their energy than they would if they were using natural gas.

“It doesn’t make sense. We have natural gas so close to the major cities, but the prices still aren’t as low and the options aren’t as clean as they could be given that there hasn’t been an adequate transition to natural gas from LPG,” Rosales said.

In June, Cenagas began developing a process to attract bids for the provision of up to 10bn ft3 of storage at one of four depleted reservoirs. Data rooms were opened and non-binding expressions of interest requested as to which of the four fields would be best suited to conversion to storage. Final bids are now expected by the end of September.

‘Importing all we can’

New gas production from onshore fields that were auctioned in recent years is not expected until at least 2020 or 2021, so Mexico’s reliance on US imports is not about to change in the short-term. If future bid rounds are halted or stalled by the incoming administration, Mexico will have no choice but to continue to rely more on its northern neighbour to meet its growing natural gas demand.

“Today we have a market with a lot of demand with limited national supply and a lot of demand for imports,” Madero said. “Every time that there is a new pipeline constructed, the ramp-up is very fast because we want to maximise the supply. We are importing all that we can.”