[NGW Magazine] China's LNG Demand Skyrockets

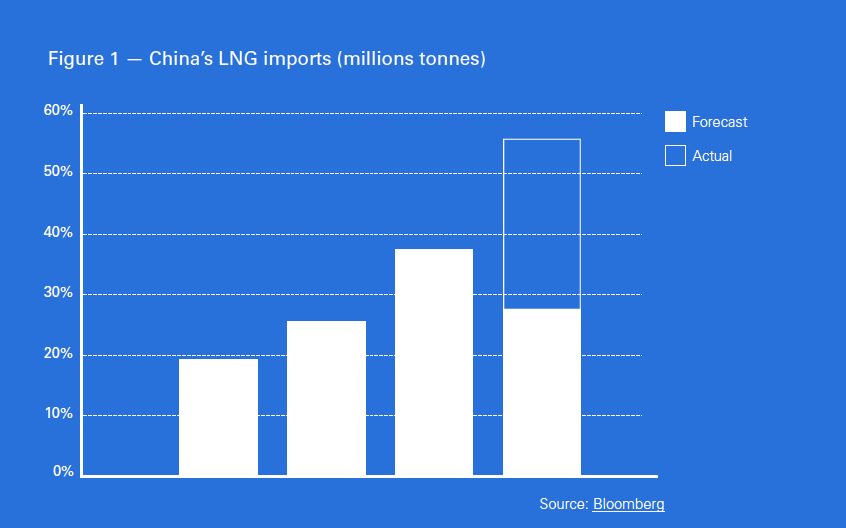

The numbers are staggering. Between 2013 and 2015, China’s LNG imports plateaued at around 18-20mn mt/yr. Then – as determined government policies kicked in to switch wherever possible from coal to natural gas – imports began to soar.

By 2016 they had grown by a third to reach 26mn mt. By 2017 they had grown by another 46% to reach 38mn mt, putting China ahead of South Korea as the second-largest importer. This year, if the current growth rate of around 50% is maintained, they are on course to reach 58mn mt – a level which will almost certainly run into import infrastructure constraints.

LNG consumption growth on this scale is unprecedented. Another year of growth at these accelerating rates would put China ahead of Japan, currently the world’s largest consumer, with imports of 83.5mn mt in 2017.

Glut? What glut?

Meanwhile, China’s hunger for LNG is affecting gas prices in markets around the world. Concerns that the supply build-up under way in Australia, the US, Russia and elsewhere might lead to a glut have evaporated – at least for now.

Even though it is still summer in the northern hemisphere, the Platts Japan Korea Marker (JKM) – a benchmark assessment for spot physical cargoes delivered ex-ship into Japan, South Korea, China and Taiwan – has averaged more than $10/mn Btu in recent months. This is the highest level in four years for this time of year, close to double last summer’s level, and high enough to encourage re-loads from European terminals. The signs are that the JKM this winter will be well over $12/mn Btu and perhaps much higher. So what is going on?

Quest for blue skies

“Coal is the dominant energy source in China,” says Li Yalan, chairperson of Beijing Gas Group Company, “accounting for 60.7% of the energy consumption structure. This has led to severe pollution and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions.

“China strongly supports the Paris Agreement [on climate change] and will fulfil its commitment to peak carbon emissions by 2030. Developing natural gas is an important measure for China to reduce emissions and tackle air pollution.”

For decades China prioritised economic growth over environmental issues as it sought to build a “moderately prosperous society”. However, since Xi Jinping took over as president in 2012 environmental concerns have risen to the top of the political agenda. China has therefore been pursuing determined policies to address the severe air pollution in its cities, especially in the north around the capital Beijing, and climate change.

So vigorous has been the campaign to address air pollution that China endured a major natural gas shortage last winter. The main focus was replacement of coal-fired heating boilers with natural gas-fired ones, which led to a surge of demand that quickly outpaced supply. Despite the shortages, the campaign to eliminate coal-fired heating in northern cities continues apace.

Aspiring to climate policy leadership

Meanwhile, China has been playing an increasingly prominent role in efforts to mitigate climate change. In partnership with the US while Barack Obama was president, China played a crucial role in the run-up to the climate change talks that culminated in the Paris Agreement in 2015.

“China has stepped up its climate leadership considerably in recent years,” says Fred Krupp, president of the Environmental Defense Fund – a prominent US-based environmental NGO which has been advising China on how to set up carbon markets. “It is now increasingly seen as filling the leadership void left by the US.”

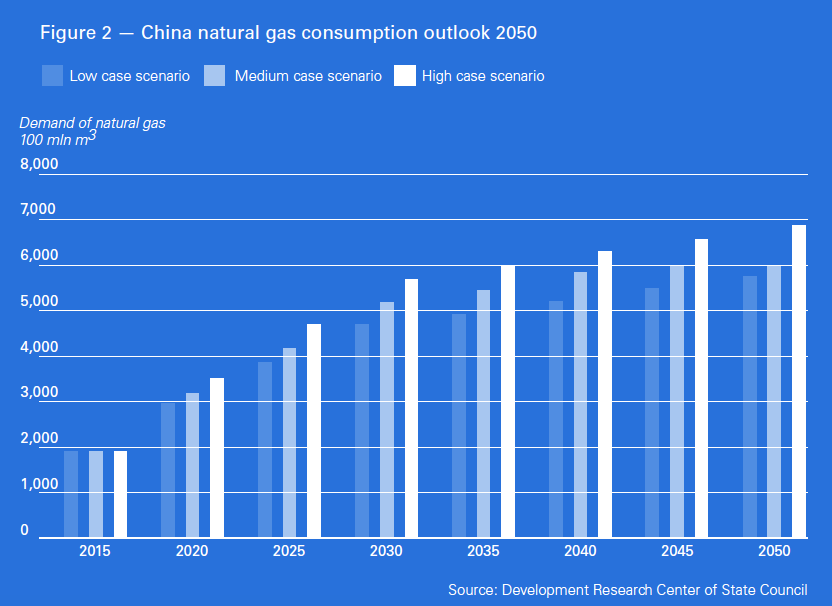

China’s climate pledges under the Paris Agreement include a target to raise the share of natural gas in the primary energy mix from around 6% in 2016 to 10% by 2020, requiring supply of 360bn m3/yr. This target also features in the 13th Five-Year Plan, which covers the years 2016 to 2020 and sets several other targets for the power sector, including raising gas-fired power generation capacity from 67.5 GW in 2016 to more than 110 GW by 2020.

To meet these targets, while avoiding winter shortages, China is doing all it can to raise indigenous gas production, but progress is not keeping pace with demand growth. The nation is therefore becoming increasingly dependent on imports of both pipeline gas from central Asia and Myanmar; and LNG from an ever-lengthening list of countries – 17 in 2017, including the US, which now poses a risk.

Pipeline imports have grown from 17bn m3/yr in 2015 to 42bn m3/yr in 2017 and growth in 2018 has so far averaged around 20%.

Racing to build delivery infrastructure

A big challenge now for China is to build more infrastructure within the country to handle growth of both indigenous production and imports. A race is on to construct new regasification capacity, evacuation and transmission pipelines, and underground storage facilities to cope with the seasonality of China’s consumption; storage capacity within China is currently woefully inadequate, at around 3% of demand.

China now has 18 LNG regasification terminals with total capacity of 60mn mt/yr, of which seven are being expanded, and another 11 are planned, says Li Yalan. She expects capacity to reach 80mn mt/yr by 2020.

So, in theory, existing regas capacity should be sufficient to handle 2018 LNG import growth. In practice, the seasonality of gas demand, with consumption much higher in winter than during the summer, means that volumes may be constrained, even if import terminal utilisation approaches 100%.

Transportation pipeline capacity is also likely to be a constraint. Last year, to work around such constraints, a quarter of the imported LNG – 10.2mn mt according to importers group GIIGNL – was delivered by truck from import terminals along the coast to customers mainly in the north.

China’s gas industry is transforming rapidly but whether the welter of activity will lead to the industry meeting its targets remains to be seen. The coming winter will be a big test.