[NGW Magazine] LNG: developing the demand

Oil prices remain an important driver of gas prices, even though direct oil-to-gas indexation is increasingly disappearing. Actually, a large part of Asian LNG imports is still indexed to oil, whereas European markets are increasingly hub-based. However, since Asian markets remain the biggest and most attractive gas market, when a price gap between Europe and Asia grows, LNG flows tend to be deviated to Asia.

Hence, European terminals are underused as prices subsequently tend to go up. Partly for these reasons, we have observed LNG prices growing in Europe in recent months. Still, Asian countries increasingly attempt to delink gas from oil. Many are unhappy with the indexation: oil price has different dynamics from gas, it depends, among others, on the dollar exchange rate and tensions in the Middle East. At the beginning of the year, Japan announced a need to phase out the indexation.

Adding to that, we also observe an end of over-supply of LNG in Asia. Japanese and Chinese consumers are complaining of LNG shortages for the mid-term supplies; most of the existing producers’ capacity is booked. Recently, Qatargas announced a 22-year LNG supply contract for 3.4mn metric tons/yr to PetroChina. This commercial deal, involving a large volume and a long-term commitment reveals China’s willingness to secure long term gas supplies. This usually happens when one expects more commodity scarcity in the longer term. The next step for European importers will be to compete with LNG supplies deviated to Asia.

LNG has headwinds in maritime transport

The IMO has introduced positive changes for LNG by cutting the amount of sulphur in marine transport from 2020. LNG will be the most logical fuel to replace high-sulphur fuel oil (HSFO): it will cut carbon dioxide emissions significantly.

From now on, the question is about commitment and compliance to these norms. The main caveat here is that ships are required to use lower sulphur fuels but refiners are not restrained by any regulation to supply heavier-but-cheaper solutions. Hence, ships will still have access to heavier fuels.

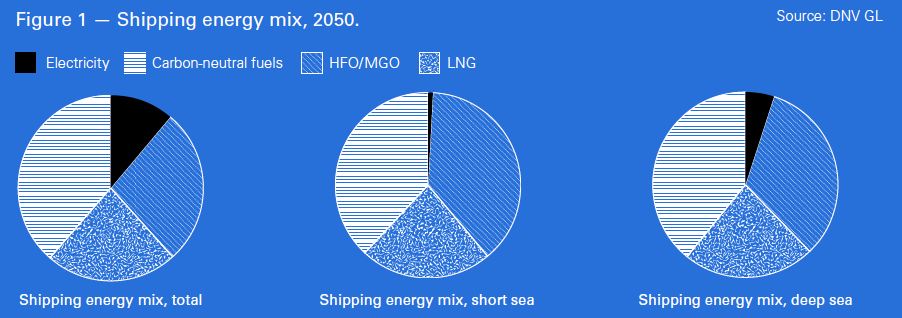

Adding to that, even though we have observed a number of ferry operators who have declared a shift to LNG, bunkering in the Mediterranean and Baltics appears to be moving more slowly than initially expected. Particularly, shipping and bunkering companies are concerned about LNG supplies and prices, whereas LNG suppliers would like to be sure of the mid-term demand for marine transport. There needs to be a faster rate of growth in the maritime transport sector in order to attract competitive LNG supplies. However, analysts remain divided about such prospects. A study recently produced by the Oxford Institute of Energy Studies points out that overall LNG demand in the maritime sector should not be overestimated. The shipping industry is not really rushing to switch over to LNG, even though we hear some announcements about companies switching to LNG for short-distance shipping: for example, liners in the Gulf of Finland.

Overall, I would believe that a further regulatory and legislative support at both national and European level might be needed to ensure the proper development of LNG markets, supplies and bunkering. Recently, Spain introduced a law obliging ship-owners to switch away from HSFO: it could be the right way to do for the other countries as well.

Adding to that, questions persist about methane. Methane actually constitutes a significant greenhouse gas emission produced during liquefaction and regasification, although the primary focus is often on the dioxide emitted by the final consumers – such as shipping companies. In this respect, a debate about “greening” the LNG will increasingly gain a place within policy communities. Mixing LNG with biogas-based liquefied gas would become one of the tangible solutions to the issue. Once again, technological mechanisms exist but a without the right regulations this development will be slow to come.

LNG trucking as forerunner

LNG shipment via containers has been increasing in recent years. Most innovative T75 Containers can for example be also used for short-term storage as the gas remains a liquid for 110 days and they can be used to ship LNG to filling stations. Rising use of compressed and liquefied natural gas in road transport certainly contributes to small-scale shipment of gas by containers.

It might be worth noting that LNG and CNG demand in inland transport seems to grow despite all the competition from electric vehicles. Across northern Europe, companies are increasingly investing in gas filling stations: in this regard, the latest news came from Gasum, announcing a plan to install up to 50 filling stations across Finland.

In some cases, containers can replace a regasification terminal. For example, Estonian company Alexela did not receive funds from the European Union for a regasification terminal which was envisaged in Paldiski, an Estonian port on the Baltic Sea. So instead it ships LNG by truck. As it turns out, the volumes remain rather limited – so far around 60,000 mt/yr – and therefore building a regasification terminal would not have been economically rational.

Nevertheless, one should not expect LNG trucking to replace large-scale shipping by pipeline gas which remains considerably more competitive. Containers represent a complementary mode for small-scale supplies. In my previous interview I mentioned LNG delivery by containers from Rotterdam to China by Sinochem. Some insiders say that is a demonstration project probably subsidised by Sinochem. In any case, the landed LNG price from this shipment was significantly higher than any LNG price in Asia.

In the longer term, LNG containers represent an interesting solution to access off-grid zones or areas with insufficient pipeline connections. Imagine eastern Mediterranean islands or the Philippines, with its hundreds of islands, serviced by LNG. It will certainly be more competitive to organise a container-based supply chain than to build a regasification terminal on every single island. Likewise, containers will be a solution for decentralised supplies in the emerging economies of Africa, south Asia and Latin America.

Certainly, any success with container-based LNG shipment will largely depend on competition with other fuels. Among illustrative examples, Gazprom supplies some LNG volumes by containers to Kazakhstan from a small-scale liquefaction plant located in the Ekaterinburg region: according to journal Neftegaz, the agreement, signed in late 2016, envisaged deliveries totalling 5,000 mt in 2017. Kazakhstan sends gas to Russia in exchange, by pipeline. Will similar projects be expanded? Probably yes, if direct gas use increases in Kazakhstan and other Central Asian states. However, gas demand remains low and competition from competitive coal remains tough in the region.