[NGW Magazine] The myth of ‘coal is dead’

This article is featured in NGW Magazine Volume 2, Issue 12

By Charles Ellinas

The phrase ‘coal is dead’ has been gaining popularity for a while now, but is it based on hard facts or are its opponents speaking too soon?

April 2015 was the first time in US’ energy history when natural gas surpassed coal as the country’s lead energy producer, and it could be said to be the date that marked the start of the ‘demise’ of coal. As cheap gas displaced coal, the first bankruptcies of US coal companies started.

By August 2015 the inevitable happened. Alpha Natural Resources, one of the world’s largest coal companies, submitted a bankruptcy filing in which it said: “The unprecedented changes facing the coal industry run deep and are occurring at a frenetic and unpredictable pace...The US coal industry as currently structured is unsustainable.”

A few days later the New York Times headline was “King coal, long besieged, Is deposed by the market.” That sent shock-waves throughout the coal and energy industry and a message that ‘coal is dead’.

By November 2015 the UK made a decision to close all coal power plants by 2025 and switch to natural gas and nuclear, making the UK the first major economy to do so. On April 21, 2017 the country had gone a full day without turning on its coal-fired power stations for the first time since 1882.

Certainly the best days of coal are over, with the US and EU shutting down old coal plants. It is also true that coal is no longer the preferred option for energy. But is coal really dead? Or is it premature to declare its demise?

Energy projections

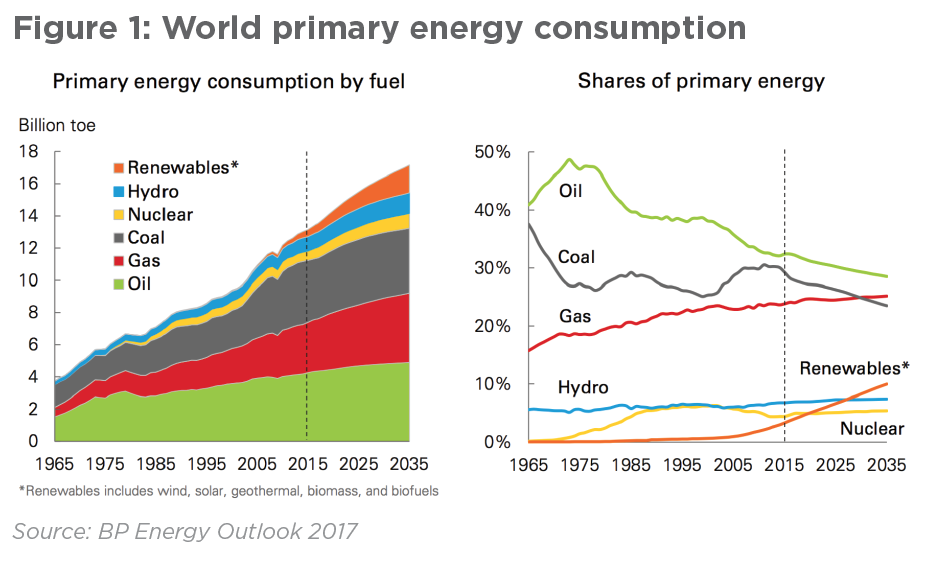

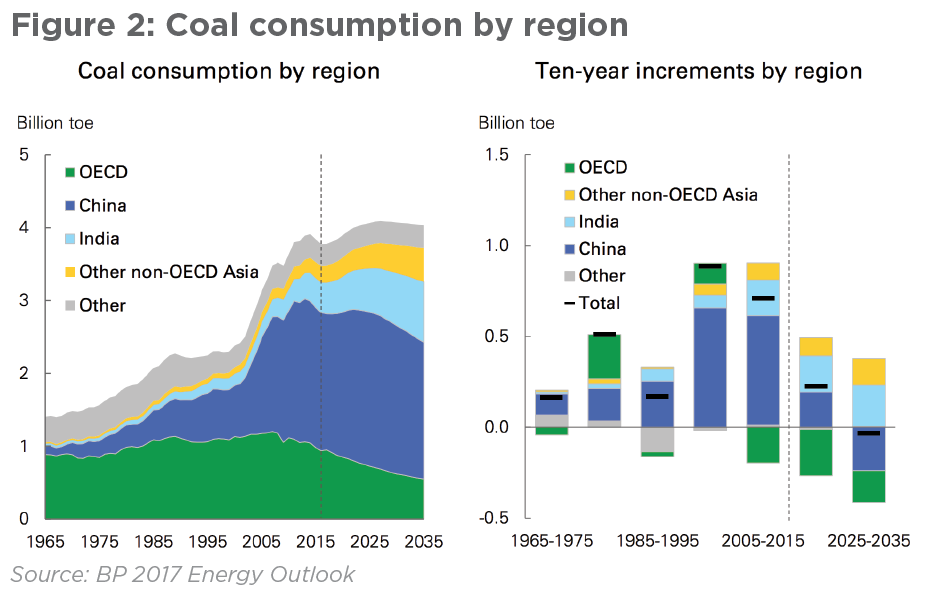

BP’s 2017 Energy Outlook (EO 2017) clearly shows that the share of coal in global primary energy consumption remained reasonably steady since 1975, varying in the range 25% to 30% (Figure 1). And even though this share is projected to decline in future, even by 2035 it is still expected to be about 24%. But more important, in real terms, global coal consumption is actually expected to increase from 3.8 bn metric tons oil equivalent (toe) in 2015 to over 4.0bn mtoe/year by 2035 (Figure 2). At this rate, if maintained, only about a fifth of the world’s total proven coal reserves will be used by 2050. A permanent glut of coal will contribute to keeping prices low forever.

Even though the use of coal has been declining in OECD countries since 2010, it has been growing dramatically in Asia since the 1990s, driven by Asia’s abundant coal reserves and low prices.

But even in Europe coal is clinging on to a significant part of future primary energy.

Coal in Europe

EO 2017 suggests that EU coal use will drop from 262mn mtoe in 2015 to 117mn mtoe in 2035, contributing only 8% of EU’s primary energy by then – still a significant contribution.

While the UK is already implementing its decision to close all its coal plants by 2025, in Germany the situation is different.

In November 2016 Germany approved its ‘Climate Action Plan 2050’. This envisages that by 2030 emissions should be reduced by 55% compared to 1990 and by at least 70% by 2040. But the plan remains vague in detail. The main reason is that phasing out coal in Germany is easier said than done because of social and political factors.

In addition, when wind and solar are not available to generate electricity, German power buyers turn to coal. Politicians talk about phasing it out by 2040 to 2050, but precise dates or plans are still lacking. End of May, Christoph Bals, political director of think-tank Germanwatch, referring to the head of government Angela Merkel said: “She rallies the international community behind decarbonisation but in Germany she hasn’t dared to set a clear timetable to phase out coal.”

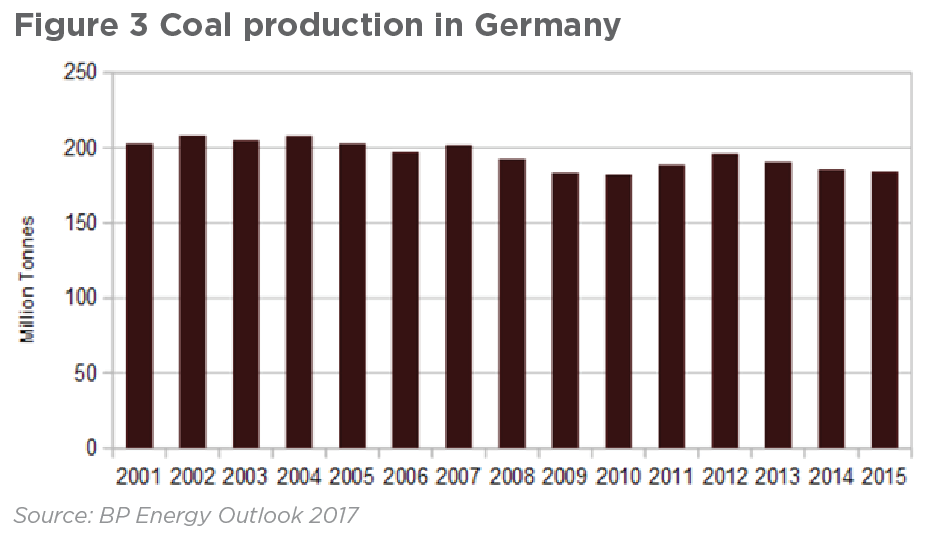

Germany’s coal production in 2015 was 180mn mt and has remained largely at similar levels for more than 20 years (Figure 3).

In Poland over 93% of electricity is generated from coal and the industry employs more than 100,000 people. In addition, the country’s deputy energy minister confirmed in March that coal production is likely to grow in the coming years, from the 70mn mt produced in 2016. He added that coal will remain Poland’s major source of energy for years.

Turkey has also changed its energy strategy and has placed more reliance on coal and lignite in its drive to reduce dependence on energy imports, driven by security of supplies and cost of imports concerns, by increasing use of indigenous resources.

Coal and lignite consumption was about 35mn mtoe in 2015, providing just under 30% of Turkey’s power generation. Turkey’s ‘Vision 2023’ plan envisages doubling of coal-fired power plant capacity.

Even though Europe is going a long way towards eliminating future coal demand, the fact that it is not going all the way makes it difficult, some call it hypocritical, to criticise others, including the US, China and India, who for their own different reasons are also dragging their feet.

Coal in the US

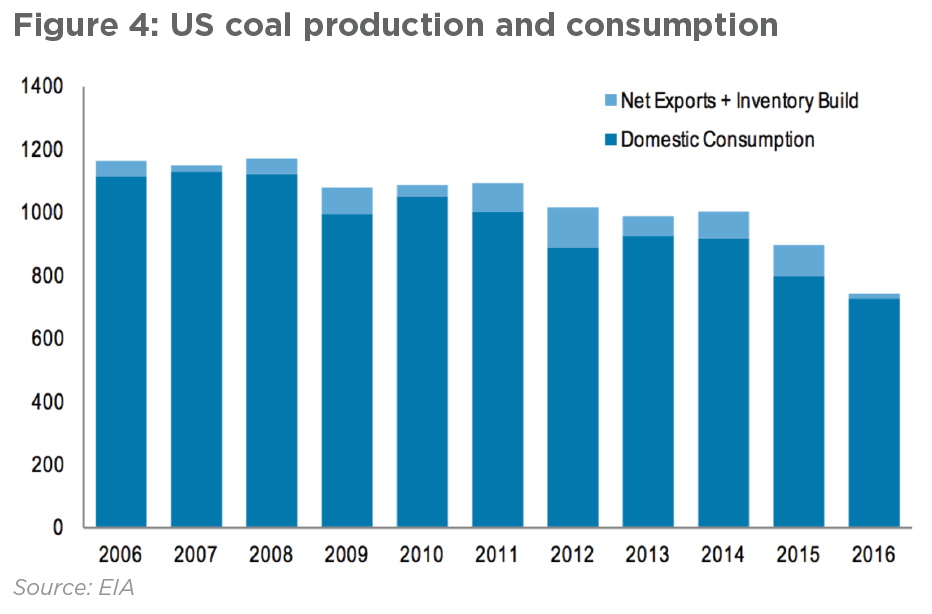

According to the Energy Information Administration (EIA), in the US coal consumption has now dropped by 35% from the peak it reached in 2008, when coal production reached its highest level (Figure 4).

Even though coal was facing challenges from Environmental Protection Agency regulations – which are now being lifted by the administration of the new president, Donald Trump – the main reason its use is going down is the low price of natural gas.

Over the last 10 years, the price of coal has averaged half that of natural gas. That changed massively in recent years. With gas down to about $3/mn Btu, it has become competitive against coal.

Combined with the fact that natural gas is cleaner, and natural gas plants respond faster to changes in power demand than coal plants, gas has been gaining an advantage. Evidently price is a major factor, stronger than regulations. If US gas prices go up significantly, coal may yet experience a return.

This price sensitivity was evident in March. The gas price increased to $3.36/mn Btu, while the coal price declined to $2.08/mn Btu. The result was an increase in coal-fired power generation and a decline in electricity production from gas in the US.

Nevertheless EO 2017 projects that the downward trend will continue, with US coal demand going down to 198mn mtoe by 2035 in comparison to 396mn mtoe in 2015 – still a substantial reduction. While the US is blessed with abundant natural gas resources, China is not, as it finds it harder to develop its shale gas resources, hence its greater reliance on coal.

Coal in China

China uses about as much coal as all other countries in the world combined, but its reliance on coal relative to other fuels has peaked and is declining.

EO 2017 suggests that coal’s contribution to China’s primary energy will fall to 42% by 2035 from 64% in 2015. However, in real terms it will remain largely unchanged, dropping to 1876mn toe by 2035 from 1920mn toe in 2015 (Figure 2).

Even though use of coal in China may have already peaked and it is declining, it is doing so only slowly. One reason may be that China is home to the world’s largest proven coal reserves after the US. Abandoning coal and relying more on energy imports, such as natural gas and LNG, brings with it security of supplies concerns.

At the end of last month Chinese authorities met with representatives of some of the largest power companies in the country to discuss the future of coal in China. The main outcome of this may be to impose extended quality checks when coal imports are processed through customs as well other restrictions, with the possibility of an eventual ban on low quality coal imports. Otherwise, there were no indications on any new changes to China’s coal policy.

However, China’s coal sector is undergoing a massive transformation that extends from the mines to the power plants, driven by the country’s determination to achieve its emission reduction targets and the demand for clean air (Figure 5).

China has also been working hard to eliminate unnecessary coal plants and future coal plant development, and over the last few months cancelled 30 large coal-fired power plants amounting to 17 GW, followed soon after by the cancellation of 104 more under-construction and planned coal projects amounting to 120 GW.

Old power plants are being closed and new ones are vastly more efficient and substantially ‘cleaner’. By 2020 all coal-fired power plants in China will have to meet stringent efficiency and emission standards.

Through these measures China intends to meet its Paris climate agreement obligations, while continuing to rely on coal, which will still be important to China’s economy for decades to come.

Clean coal trumps Indian renewables

India relies on coal for close to 60% of its primary energy. And even though, according to EO 2017, this will decline closer to 50% by 2035, in real terms coal demand will more than double from 407mn toe in 2015 to 833mn toe by 2035 (Figure 2).

However, India is taking measures to achieve its emission targets and it recently doubled its tax on coal, and has announced it will not build capacity beyond what is planned and under construction until 2027, prioritising new power generation capacity from renewables.

But India’s power minister, Piyush Goyal, says there is a limit to how far and fast India’s economy can move beyond fossil fuels. India will continue investing in new coal plants. According to the minister, it will only be with a foundation of reliable thermal power that the country can absorb large amounts of intermittent renewables generation.

But the coal plants being built are more efficient and therefore less polluting than older power stations. Goyal argues that this shift towards ‘cleaner’ coal will make a bigger impact on Indian emissions than all its renewables combined.

Cheap coal is also a factor and carbon pricing is a challenge. In an interview in the Financial Times in May Goyal said “Thirty per cent of our people are living in poverty…I cannot tell them: British people have benefited from coal-based power for 200 years and have spewed all that carbon up there and now India will pay three times the cost.”

There is a view that India’s growing needs can be met only by considering all options and that cleaning up coal plants and promoting renewable energy go hand in hand – it’s not a choice between renewables and coal.

However, measures taken by the Indian government to improve energy efficiency and the plummeting cost of solar are having an impact on existing as well as proposed coal-fired power plants, and may yet lead to further shifts in the balance between renewables and coal.

Rest of the world

EO 2017 projects that Africa will experience the fastest energy demand growth among the world’s regions, between 2015 and 2035, driven by urbanisation, rising population, and strong GDP growth. A significant part of this growth will be supported by coal, consumption of which will increase from 97mn toe in 2015 to 121mn toe in 2035.

According to EO 2017 another region of the world to experience large growth in coal demand is ‘Other Emerging Asia’, which includes all of non-OECD Asia apart from China and India. Coal will be providing about a third of primary energy by 2035, with 467 mn toe in comparison to 219 mn toe in 2015. Even Russia will continue relying on coal for 10% of its primary energy, using its vast proven coal reserves, despite the fact that it is a major oil and gas producer. Russia is projected to be consuming 69 mn toe in 2035 compared to 89 mn toe in 2015.

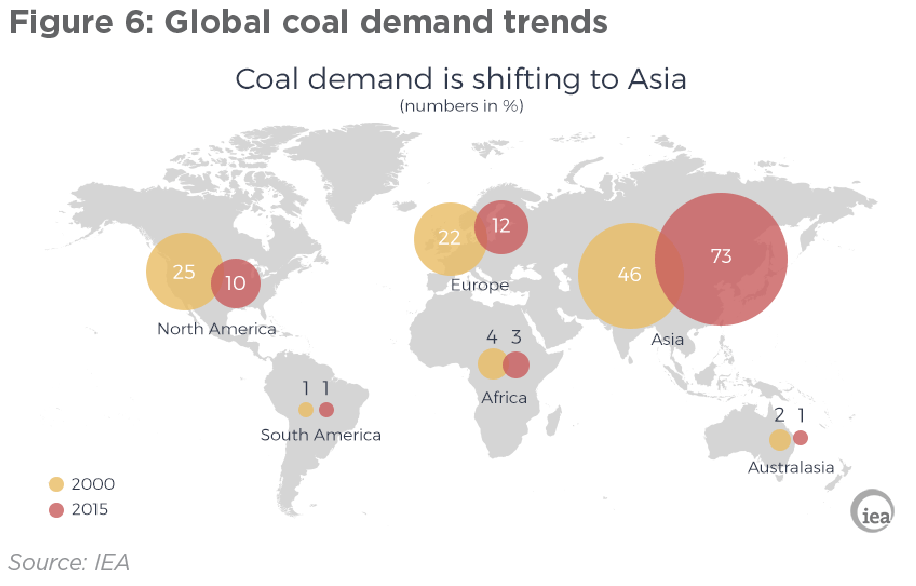

In its ‘Medium-Term Coal Market 2016’ report the International Energy Agency (IEA) has shown that clearly coal demand has been shifting to Asia (Figure 6).

In 2000 about half the global coal demand was in Europe and North America. By 2015 that declined to less than a quarter, with Asia accounting for almost three quarters of global coal demand.

Implications for natural gas

In the US natural gas is squeezing coal out because of low prices, but not permanently. New government policies may not lead to revival of coal but may yet stem its decline.

The switch from coal to gas may be accelerated if serious carbon pricing is introduced globally. In its new report published in April, the Energy Transitions Commission (ETC), an independent body convened to help identify pathways for change in global energy systems to ensure both better growth and a better climate, called for carbon pricing reaching about $50/mt in the 2020s and rising to around $100/mt in the 2030s.

Most of the international oil companies are supporting this. But the reality is that it is not in place now on the scale required – even in the EU where this is taken more seriously. Certainly it is difficult to see it introduced in the US and other major countries relying on coal will find it difficult to move in that direction.

The ETC report also calls for ‘unabated’ coal to start declining immediately. Clearly this is not happening and is not about to start happening either.

In this article we have shown that ‘coal is indeed not dead’ and even though its use is not growing globally, nevertheless it will continue being a major part of the global energy mix for a long time – 24% by 2035 according to EO2017.

On the other hand the Eighth Clean Energy ministerial meeting, organised by the world authority on carbon capture and storage (CCS) in Beijing on June 8, identified CCS as key to the decarbonisation of coal and gas, but also in broader industry applications. China has ramped up its efforts to develop and use CCS to decarbonise its coal-fired plants. But wider deployment of CCS is still facing challenges.

In Asia, where most of the coal will be consumed in the future, the decommissioning of ageing, inefficient, coal plants and their replacement with more efficient plants burning ‘cleaner’ coal will help control emissions and in China’s and India’s case within their Paris agreement pledges.

Even allowing for limitations in long-term forecasts, such as BP and IEA, nevertheless coal will be an important contributor to global primary energy well into the future. Because of its low price, in comparison to its competitor gas, and its wide availability, coal maintains a strong position in the world’s primary energy mix. It is too early to call its demise.

The key message though is that switching from coal to gas globally – much needed and called for by the gas industry – may not be happening to the extent required. Cheap coal is hard to beat.

Charles Ellinas