[NGW Magazine] Aphrodite Dispute Rises up Agenda

A claimed extension of a Cypriot gas field into Israeli waters could complicate gas sales agreements involving the export of Cypriot gas: uncommercial on its own and ignored, it is of great interest if it is an appendage of Aphrodite.

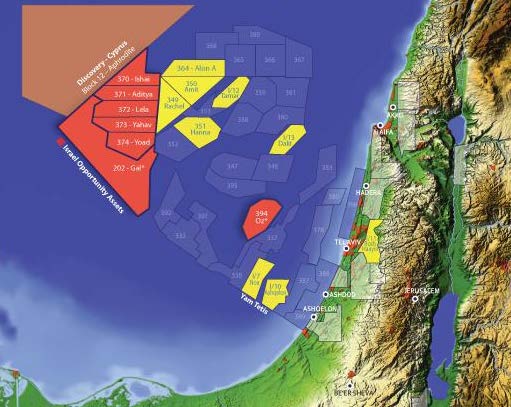

The owners of the Ishai Pelagic licence, on the Israeli side of the Israel/Cyprus exclusive economic zone (EEZ) boundary line, remain in disagreement with explorers in Cyprus over the government’s claim to the gas reserves in Block 12 (Figure 1). They maintain that Aphrodite extends into Ishai; and the two sides, together with the Cypriot and Israeli governments, have been in negotiations for seven years with no unitisation agreement in sight. This is in danger of poisoning relations between two friendly neighbouring countries as Block 12 is developed. The owners of Ishai are Israeli companies Israel Opportunity Energy Resources, Nammax Oil & Gas, Eden Energy Discoveries and AGR Petroleum Services Holdings. Their position, which the Israeli energy ministry supports and is responsible to pursue on their behalf, is that the quantities of Aphrodite natural gas that extend into Ishai are about 7bn m³ to 10 bn m³, compared with about 100bn m³ in Block 12.

Figure: 1 Cyprus block 12 and Israel’s Ishai Pelagic licence

Credit: Israel Opportunity

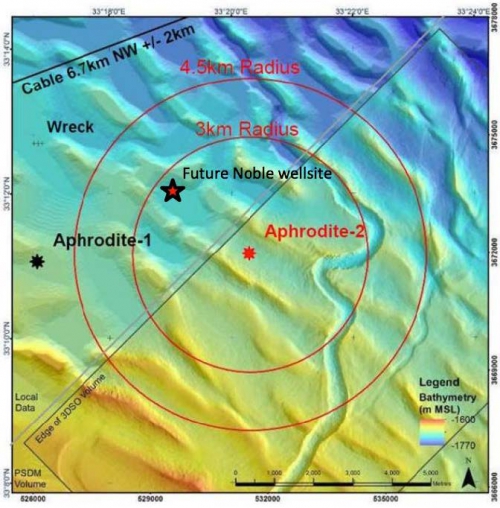

In order to understand the significance of these figures, if the profit from selling the gas is $2/mn Btu, then the profit for 10 bn m³ comes to about $0.7bn and the Israeli companies also claim they have already spent $120mn on exploratory drilling – including a well they named Aphrodite-2, about 1 km from the boundary line between the two EEZs (Figure 2). The well was drilled in 2013 and it was reported that significant signs of hydrocarbons were found in the lower Miocene sands. The natural gas bearing layer was estimated to be some 15 metres thick, but it was declared non-commercial. However, the Ishai owners are using this as evidence that Aphrodite extends into their licence. In 2015 Israel classified the Ishai license as a gas discovery, an aggressive step that indicated that Israel is serious about this claim.

Figure 2: Ishai well Aphrodite-2

Credit: Searc Consulting

Israel is entitled to 60% of any profits, which is one reason that, according to daily business paper Globes, Israel’s minister for national infrastructure, energy, and water, Yuval Steinitz, to say: "The state did not forego the Ishai prospect, and will not give up its share, even if this part is relatively small.… The state will not waive its share of either the gas or the revenue from the Aphrodite reservoir, and is also unable to do this in the name of the companies that hold it."

Globes specifically said that in the absence of a unitisation agreement, Israel will not agree to Cypriot plans to develop Aphrodite. Cyprus’ energy minister, Yiorgos Lakkotrypis, acknowledged that this is one of the most important issues facing Cyprus and Israel.

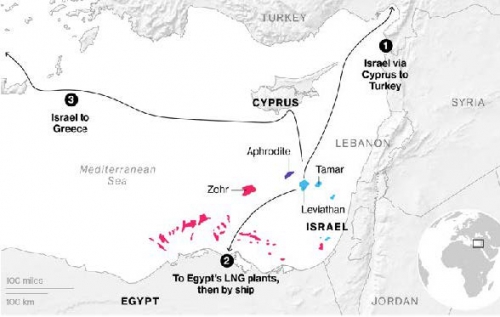

Steinitz also connected this problem with the EastMed gas pipeline. He said that "Israel has an interest in this, because it brings closer the construction of a pipeline to Europe and exports to Egypt (Figure 3), if a pipeline to that country is built later. This means money for the state - that is not something we take lightly." Israel has a stake in both sides of the dispute, through Delek: as one of the Block 12 licensees, it disagrees with this claim.

Figure 3: Eastern Mediterranean gas export options

(Credit: Bloomberg)

The Block 12 owners, which also include Noble Energy and the Anglo-Dutch major Shell, disagree with the Ishai claim. Their position is that Aphrodite does not extend into Ishai, and that even if it did, any amounts of natural gas are less than 1%. Such differences are not unusual in the global oil and gas industry. To avoid them, neighbouring countries usually conclude agreements, known as unitisation agreements, immediately after entering into EEZ delineation agreements, defining the boundary line between their two EEZs. This has been done, for example, between Cyprus and Egypt, who reached such an agreement in 2013.

It safeguards the rights of both countries and companies and specifies the method to be used in agreeing separation of resources, as well as for dispute resolution. So when there is a problem, there is a predetermined legal framework that helps to find a solution and reach agreement. It also specifies steps to be taken, such as arbitration, to resolve disputes if they persist.

Unfortunately, this was not done between Cyprus and Israel, even though the EEZ delineation agreement was signed in 2010, leading to the present situation. So now instead of having differences between companies, the problem also involves both governments. The good news is that Israel and Cyprus recognize the need for one and may be prepared to enter into a process to reach a successful resolution of the problem. The first step would be a final attempt to reach an agreement between the companies involved, over the next few months. If this does not have the desired effect, the two governments could intervene to get the problem referred to international arbitration. Without an agreement to resolve Aphrodite's problem between the companies involved, referring this to international arbitration may be the right path for a final solution. And given its political ramifications it is becoming urgent. Following the May 8 meeting in Nicosia between the leaders of Israel, Greece and Cyprus, Benjamin Netanyahu said in public that the dispute could be settled within six months, but did not elaborate on Israel’s position. However, an Israel official, who asked not to be named, said: “The professional opinion of the Israeli government is that at least 5% of the reservoir is in Israel.… The dispute with the Cypriots is about how the Israeli share will be guaranteed because it’s the Cypriots who will be developing the field.”

Meanwhile, unitisation agreements are on the agenda of a future meeting between the governments of Israel, Cyprus and Greece. Better yet, it is becoming necessary to enter into such agreements as soon as possible in order to avoid any potential future problems. The same must be done with Lebanon.

What has brought the Aphrodite problem into the limelight is the likelihood of Cyprus selling natural gas to Egypt – something which has been receiving increasing press coverage over the last few months. Noble Energy is in talks to sell Aphrodite gas for liquefaction at Shell's liquefaction plant at Idku. There are also talks to export it to Egypt’s domestic gas market. The two countries' governments are also in talks on this.

Should such gas sales agreements be reached, the Ishai Pelagic licensees cannot prevent them, but without resolution of their claim through arbitration they might pursue their case through the courts. This may complicate Aphrodite's development, but it will not slow down efforts to export other gas from the region. Irrespective of the specific problem, Cyprus and Israel are very close at the political level and this state of affairs will continue. Israel sees urgency in reaching an agreement with Cyprus to resolve this dispute, because of its financial interests, but also those of the Israeli companies in Ishai. If Cyprus starts developing and exporting Aphrodite's gas without achieving resolution of this dispute, Israel is worried that it may incur significant financial losses.

It is expected that shortly a, non-commercial, inter-governmental agreement will be signed by Cyprus and Egypt to facilitate the transfer of natural gas through pipelines from one country to another, specifically facilitating the transportation of Aphrodite gas to Idku. However, without a final gas sales agreement between Noble Energy and Shell, the inter-governmental agreement remains an agreement on paper.

And that is where the problem lies. Global gas prices are low and many expect them to remain low in the long term owing to the relentless penetration of renewables and an abundance of energy resources. In order for a deal to be reached between Noble Energy and Shell, the former has to accept a very low gas price, to the point that it would hardly meet its expectations and justify its investments. Cyprus may be seeking such a sale for political reasons, but it is in danger of selling out its gas.

A better development plan for Aphrodite may be for Cyprus’ domestic market, including power generation and desalination, and for the development of petrochemical industries in Cyprus. But if the expected plan to import LNG to Cyprus on a long-term contract goes ahead, such opportunities may be delayed or even missed.

Finding the right legal solution

In the oil and gas industry the resolution of disputes through arbitration is well-established. Independent arbitration usually includes a complete set of procedural rules on the basis of which the parties may agree to conduct arbitration and resolve disputes arising from their commercial relationship. International organisations that offer such services include: United Nations Commission on International Trade Law (Uncitral), Paris-based International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) and Washington-based International Center for Settlement of Investment Disputes (Icsid). Icsid is an international arbitration body established in 1965 to resolve legal disputes and conciliation between international investors. It has 161 member countries, including Cyprus and Israel and its arbitration has many unique features that can be used to solve the problem. It is deliberately structured to reflect the balancing of interests between the states and investors involved and provides a depoliticised and effective dispute settlement mechanism.

It is also a self-imposed system which, unlike arbitration through ICC or Uncitral, is wholly independent of national courts because Icsid's arbitration is conducted only in accordance with international law and regulations and rules. Arbitration decisions under Icsid are binding on the parties and are not subject to any appeal, other than those provided for in the Icsid Conventions. National courts have no power to revise decisions in any way.Icsid is of particular importance to the oil and gas industry, which accounts for most of Icsid's legal traffic. Investments in this industry are usually fairly large and complex, and are often concluded with government agencies or organisations, as in the present case. In many cases, because of the security or strategic importance of these industries, the conflicts, if and when they come, are often politically charged as they appear to be in this dispute. Icsid was specially created to resolve such disputes.

Charles Ellinas