[NGW Magazine] China Balances Coal and Gas

JLC Network Technology is the leading information provider in China, analysing commodity markets, including oil, gas and coal. Sue Su and her colleagues at JLC shared their views on the prospects and risks facing China’s LNG supply and demand.

The headlines at the end of 2017 were that soaring China demand could tip the balance in LNG markets. The view was that runaway gas demand in China is transforming the future of LNG. What led to this and is it long term?

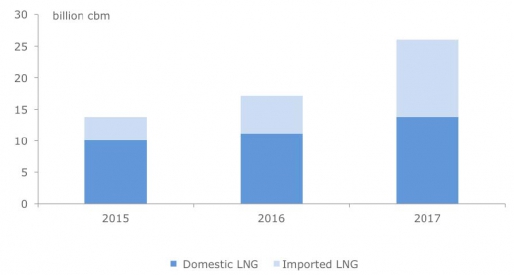

End users going through coal-to-gas conversion shifted to LNG owing to the relatively slow pace of pipeline construction, as the environmental regime became harsher. This pushed up the use of LNG sharply (Figure 1). China’s LNG import demand hit 26bn m³ in 2017, up 53% year-on-year.

Figure 1: China's consumption of LNG in 2015 to 2017

Source:JLC; cbm=m³

Moreover, the earlier, low LNG prices had incentivised many investors to purchase LNG-fuelled heavy trucks. That, and the greater amount of switching from coal, have pushed up end-use demand.

Heavy trucks will persist in the long-term, which will shore up the LNG market and help the LNG supply chain development.

This is evident from February imports of LNG, which stood at 3.99mn metric tonnes (mt). Even though this is down from January’s 5.18mn mt, which was the result of milder weather which will continue to dampen LNG imports, nevertheless they were 69% up on February 2017.

Coal-to-gas switching was probably the driving factor. Do you expect this to continue and will coal demand in China fall significantly from now on?

Coal-to-gas switching will undoubtedly be a key driver in natural gas use. But it is a gradual process. Coal is not only used in power generation, but also as an industrial fuel in other sectors such as heavy industry. Therefore, it is too early to say coal demand will decline significantly, but it will not continue growing as before.

LNG demand has grown rapidly over the last few years. Was what happened in 2017 unexpected?

Last year’s sharp growth in China fell within our expectations. The problems happened because the coal-to-gas switching was carried out to its maximum in the year.

What was unexpected was the shorter-than-normal supply from domestic LNG plants in winter owing to various factors, which tightened the supply-demand balance. There are seldom supply shortages in summer, and we do not see the shortage repeating in future years.

What is the impact on infrastructure, such LNG import terminals and distribution? Has that led to changes that mean that this year will be easier?

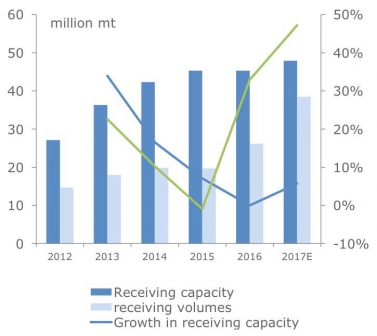

LNG receiving storage capacity at the terminals has been growing slowly (blue line in Figure 2) not in line with the faster growth in receiving volumes (green line in Figure 2) which might somewhat impact natural gas supply.

Figure 2: Utilisation rates of China’s LNG terminals, 2012 to 2017 (left axis: receiving capacity and volumes in mn mt – right axis: growth rate in %)

Source: JLC

This is being improved. However, LNG import terminals were not overused, and they played a key role in easing the gas supply shortage in 2017. Of course, China will continue to improve its natural gas infrastructure in 2018, including both storage and reception terminals.

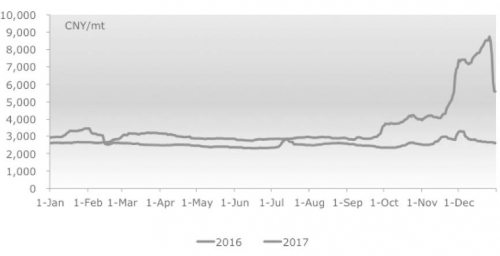

There was also a big impact on prices which I am sure China does not want to see repeated in 2018. How do you see prices developing?

Gas shortages in Q4 2017 led to a price surge, but prices subsequently tumbled (Figure 3). LNG prices are expected to be more stable in 2018 than 2017, with extra-high levels unlikely to show up.However, LNG prices will be higher than a year ago for most of the year as demand is stronger.

Figure 3: LNG prices in China, 2016 to 2017

Source: JLC; CNY=yuan

High prices surely have an impact on the future uptake of LNG in China, on the competitive position of gas against other fuels and on coal-to-gas switching. Can you comment on these?

Undoubtedly, extremely high LNG prices will lower demand, as end users will seek more suitable and lower cost alternatives. They will also slow down the coal-to-gas switching. However, extremely high LNG prices only appear occasionally, and it is not a long-term scenario.

Also high dependence on imported LNG has implications for the security of supplies through dependence on other countries, which is not the case for other resources such as coal and renewables. Will this be an important factor in terms of how China's LNG market develops in the future?

The rapid development of natural gas demand in China is attributed to the government’s push to improve air quality and create better living environment for the people. Hence, even though China is totally self-sufficient in coal, it cannot affect natural gas use and the development of the market. Moreover, China is actively lifting its output of both conventional natural gas and non-conventional natural gas.

What are the changes in China's LNG markets, including supply and demand, as a result of the 2017 experience?

China’s LNG supply includes domestic and imported LNG. Imported LNG took a much larger share of the total gas supply last year and the country’s consumption of imported LNG is expected to exceed that of domestic LNG in the next couple of years. Industrial users and vehicles will be the two largest consumers of LNG.

What future opportunities does China present to LNG traders and suppliers, but also to Chinese importers?

China’s LNG trade increase has generated more opportunities for traders. Chinese suppliers have more chances to access the market or expand production, and Chinese importers have more chances of buying more and enhancing their clout in pricing negotiations with overseas suppliers.

There are many who believe China's LNG demand will soar and are already planning new projects. Do you see this happening and can you forecast what this demand will be between now and 2030?

There are new construction plans for both LNG plants and receiving terminals. It is predicted that over 2.7mn mt/yr of LNG domestic production capacity and close to 12mn mt/yr of LNG receiving capacity will be added in 2018 (Figure 4). It is hard to make predictions for the next 30 years, but natural gas demand looks set to increase rapidly in the next three to five years, in line with expectations [see: NGW_Vol2_Issue12 – p.6].

Figure 4: More LNG receiving terminals to come online in 2018

Source: JLC

What is the impact of this on pipeline gas? Is China going to turn to central Asian and Russian pipelines to bolster its gas supplies? Can you say anything about quantities and sources?

China’s natural gas imports via China-Central Asia Pipeline are set to increase. The China-Russia Pipeline is set to start in October 2019. China’s strengthening gas demand will lead to more imports of pipeline natural gas and LNG. Australia, accounting for 45% of China’s total LNG imports, is China’s largest LNG supplier, followed by Qatar and Malaysia. China’s LNG imports from the US and Russia will obviously rise in 2018.

Is China going to put more emphasis on producing more gas domestically, both conventional and unconventional? On paper China has huge potential for shale gas, but it is difficult to develop. Will this now get a boost and can you forecast on what such production could be by 2030?

China will ramp up both conventional and nonconventional natural gas output, according to the 13th Five-year Plan. China is rich in shale gas, but it really faces some technical problems in developing it. However, there are already pilot shale gas projects and its shale gas output will be on the rise in future.

What is the impact of all these developments on China's energy fuel mix between now and 2030, and will they lead to changes to China's 13th Five-Year Plan?

China is promoting energy structural adjustment, aiming to develop natural gas into one of its major energy sources. The coal-to-gas switching has achieved effective results in improving air quality and natural gas usage direction will not change in the next couple of years. China is also prioritising wind, solar, hydro and nuclear power projects. The share of non-fossil fuels in China’s energy demand is expected to rise to 15% by 2020.

Charles Ellinas