[NGW Magazine] Canadian NGLs: Where is the Value?

The shale gas surge in North America offers new Canadian domestic and export petrochemical opportunities, as the liquids output is rising fast. The question is when to extract them – before or after liquefaction?

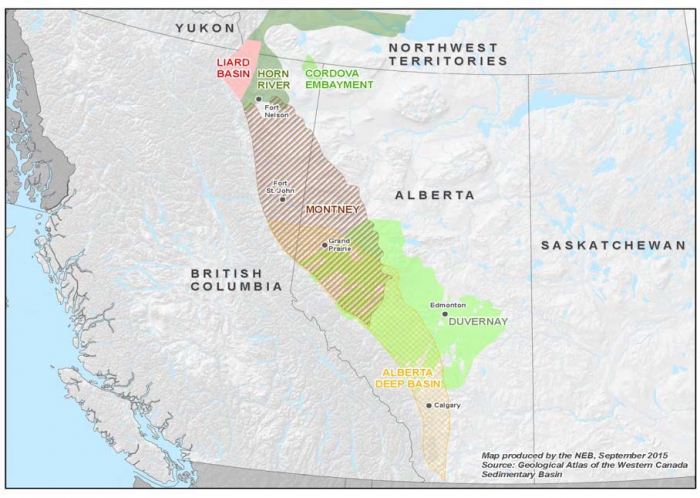

A by-product of surging North American shale gas production – largely from the Marcellus and Utica basins in the US and the Montney play in Canada – is a flood of natural gas liquids hitting the market in both countries.

In the US, according to recent Energy Information Administration (EIA) data, the production of natural gas liquids (NGL) – ethane, propane, butane and condensate – has nearly doubled since 2010, outpacing even natural gas production growth rates as drillers focus on liquids-rich ‘sweet spots’.

Ethane accounts for more than half the US NGL production, and in 2017 averaged about 1.4mn b/d, up from less than 900,000 b/d in 2010, the EIA says.

Canadian ethane production, however, has remained relatively steady over the last several years, according to statistics from the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers, reflecting little growth in feedstock demand from western Canada’s ethane-based petrochemical industry.

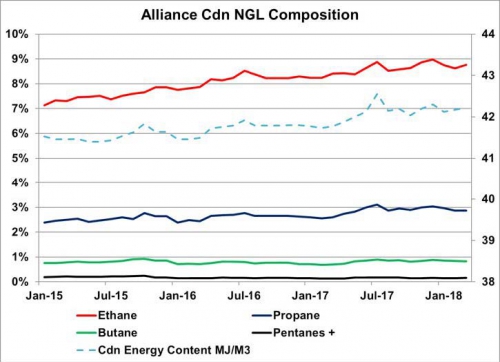

Another measure of ethane use in western Canada is the percentage of the liquid left entrained in the wet gas stream moved from Alberta to liquids extraction markets in the US Midwest by the Alliance pipeline, Dave Tulk, a partner in the gas consulting firm GTI, told a recent petrochemical conference hosted by the Canadian Energy Research Institute (CERI).

Credit: GTI

“Ethane content in the Alliance stream has grown steadily over the last few years, from 7% in 2015 to about 9% this year, which means that there is a huge amount of ethane available,” Tulk said. The Montney formation alone, he said, contains an estimated 14.5bn barrels of NGL – more than half of which is ethane.

And that volume of ethane, he said, offers opportunities throughout the natural gas value chain: left in gas exported as LNG to Asian markets it could increase the value of those exports by between US$300mn/yr and $600mn/yr; extracted close to production fields in northeastern BC and northwestern Alberta, it could provide additional feedstock to support an expanded western Canadian petrochemical industry; extracted at tidewater, upstream of liquefaction terminals, it could support either a new petrochemical industry in British Columbia or exported directly as ethane to Asian markets, as many US producers are doing.

“LNG exporters, obviously, are going to be looking to get rich, high energy gas because the ethane content in that gas would effectively add $1/mn Btu to the AECO gas price,” Tulk told the conference. “That is going to change the dynamics of the western Canadian gas industry and it will also have an effect on the NGL industry.”

This may be a desired option for integrated LNG export projects with Asian partners who might already have plans to extract the ethane downstream of the regas terminal, he said

But the economics of extracting the ethane in Canada can be just as compelling, Tulk said. A typical LNG feed gas stream of 2bn ft³/day would yield 90,000 b/d of ethane and 36,000 b/d of propane and generate a net operating profit, if extracted at tidewater and exported to Asia, of more than US$200mn/yr for the ethane and at least US$325mn/yr for the propane.

Waterborne exports of ethane to Asia and India have risen rapidly in the last couple of years, Tulk said, based largely on the over-supplied US ethane market. “For example, there are now six very large ethane carriers dedicated to moving ethane from Houston to an ethylene cracker near Mumbai, India via the Suez Canal, and similar projects are underway to supply ethane markets in China.”

Credit: National Energy Board

Ethane exported from Prince Rupert (on BC’s northern coast) enjoys a significant distance advantage over exports from Houston, Tulk added: China is less than half the distance, as are markets in Japan and South Korea, while even Mumbai is nearly 2,000 km closer to Prince Rupert than to Houston.

But ethane extracted at tidewater need not be exported in its raw form, Tulk said. It could also be used to support the development of a new petrochemical cluster on Canada’s west coast, which would also enjoy similar advantages as ethane exports.

“An extraction facility at Prince Rupert would generate enough ethane to support a world-scale cracker, which would supply enough ethylene for three world-scale derivative plants, producing polyethylene or ethylene glycol,” he said. And since Prince Rupert is already a world-class intermodal port, infrastructure already exists to support the export of those derivatives.

And propane extracted at tidewater would provide a “large cost advantage” for BC NGL export terminals – one such propane terminal is currently under construction; a second is expected to reach FID early next year – over propane delivered by rail from Alberta.

Extracted closer to production fields, with a new straddle plant near Fort St John, would provide increased ethane supply to the Alberta petrochemical industry, which has suffered from declining investments in recent years, according to the executive director of Alberta’s Industrial Heartland Association, home to the Alberta petrochemical cluster.

“A significant percentage of investment in the petchem space has taken place in the US, and the percentage that Canada typically saw in the last five years has declined dramatically,” Mark Plamondon told CERI conference delegates, noting the US attracted US$185bn in petrochemical investments in the last wave of development.

Still, with the momentum generated by the Alberta government’s Petrochemical Diversification Program and its Feedstock Infrastructure Program, combined with the federally-administered Strategic Innovation Fund, there is future opportunity for renewed petrochemical development in Alberta and western Canada, he said.

Opportunities do exist, Plamondon said, for future investments in methanol production (Methanex is thought to be contemplating an expansion of its 600,000 mt/yr facility at Medicine Hat), ethane and propane derivatives, fertilisers and speciality chemicals. But regulatory uncertainty, protectionist sentiments, incentives offered from other jurisdictions and capital cost profiles available to Canadian investments could take some of the edge off those opportunities.

“We believe, looking at the opportunities in front of Alberta and western Canada, that there is an opportunity right now for C$30bn in petrochemical investments and value-added energy investments between now and 2030,” he said. “But there are some risks and headwinds that in my view take that optimism and turn it into cautious optimism.”

Dale Lunan