[NGW Magazine] Making the Southern Gas Corridor Work

Now that the gas is beginning to flow into the TransAnatolian Pipeline, attention is turning to the next phase of the giant project and how the economics of developing Shah Deniz 2 and 3 stack up.

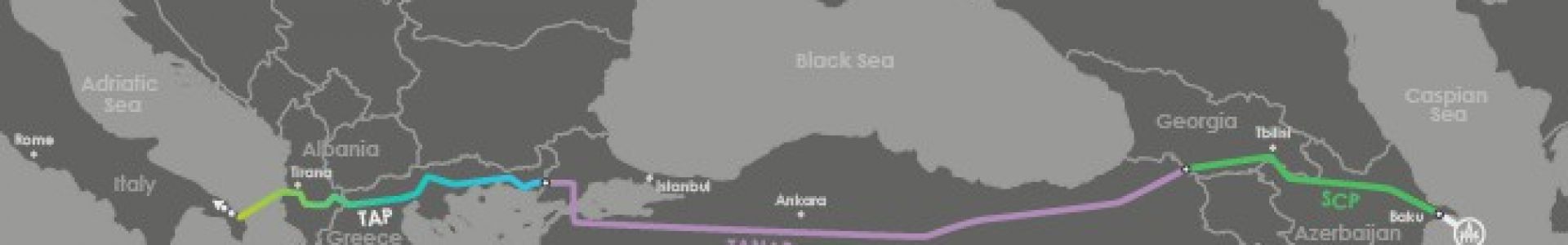

The Southern Gas Corridor’s (SGC) first section, from offshore Shah Deniz gas field to the town of Eskisehir in eastern Turkey, started up initially in May and June, while the rest of route is under development. It will supply 6bn m³/yr to Turkey and 10bn m3/yr to the EU from Shah Deniz stage 2 (SD2) by 2020; and the project is planned to expand to reach 31bn m3/yr by 2025. To what extent the project profitable will depend on circumstances beyond the shareholders' control, but the costs have been cut and the production-sharing contract gives the investors some assurance. The other question is, will Tanap be able to reach the planned 31bn m³/yr capacity by relying solely on Azerbaijan’s own gas?

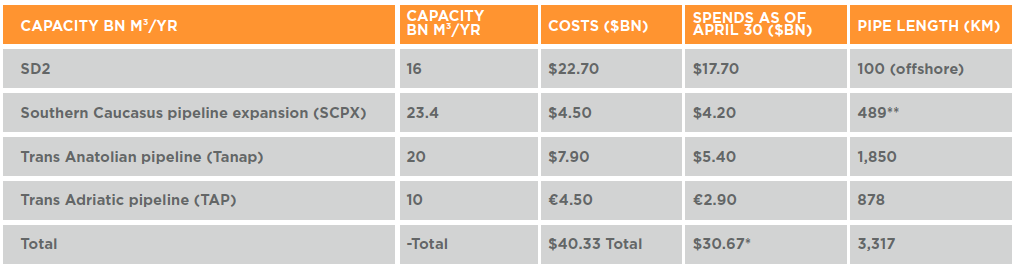

Southern Gas Corridor costs

Source: SGCC documents, seen by NGW. * Some companies are yet to complete their costings. ** SCPX is connected to SCP, operational since 2007. In total, their length is 1,181 km.

The whole field includes SD1 which has about 11 years’ production history, and is a smaller model of SD2. Shah Deniz participants are operator BP with 28.8%, Turkish state upstream producer TPAO (19%), Azerbaijan’s state-owned Socar (16.7%), Malaysian state Petronas (15.5%), Russian independent Lukoil (10%), and Iranian state Nico (10%). The same companies have the same stakes in SCPX as well. In total, Azerbaijan holds a quarter of the stakes in the entire SGC, including SD2.

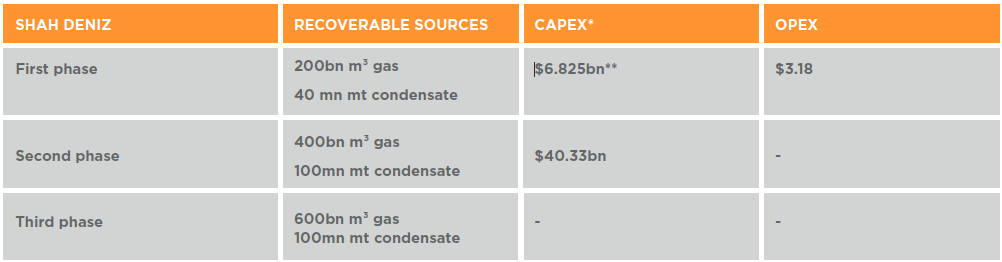

The field contains 1.2 trillion m3 of recoverable gas and 240mn metric tons (mn mt) of condensate, of which a sixth is in the SD1 layer. SD2 is twice the size of the first phase, and the other half of the total gas is in the third phase.

From 2007 to 2017, SD1 produced some 88.5bn m³ gas as well as 22.5mn mt of condensate and all the $10bn spent on SD1 has already been recovered.

* Including $2.5bn up/downstream, $5.1bn Baku-Tbilisi-Erzurum pipeline costs.

Currently SD1 produces up to 10bn m3/yr, of which two thirds are exported; but the level will dramatically decrease in 2028, when the contract period finishes. On the other hand, SD2 will then enter its second half-life and face a pressure fall in early 2030. That means that SD3 is vital if exports are to stay constant.

The production-sharing agreement (PSA) for SD2 is 25 years. The Azerbaijani government receives 70% of the profits from production once the shareholders have recovered their total expenditures. That means the shareholders will recover their investment in a relatively short time.

Regarding gas production and processing costs, the figure for SD1 was $43.95/’000m³ on average in the last decade. The figure is profitable, because even the lowest sale price – paid by state-run Socar which buys a third of it – is as high as $57-65/’000 m3, based on two separate contracts. The rest of the gas goes to Turkey where it is sold at above $200/’000 m³.

Georgia takes 5% of the total gas export volume to Turkey – regardless of the gas source – as transit fee, based on a 40-year contract, signed in 2007 between Azerbaijan and Georgia.

That means Georgia receives 1.125bn m³/yr as transit fee from SD1’s 6.5bn m³/yr and 16bn m³/yr from SD2 gas transit after 2020, which would account for 45% of its total demand in early 2020s. Azerbaijan’s state-run Socar also separately exports gas to Georgia, which only receives gas from that country.

After gas deliveries to Georgia rise in 2020, its dependence on Socar’s own gas falls and Socar can supply more gas to domestic markets. SD2 will cost four times as much as SD1 to develop, but the volume of reserves, production rates and the gas price is also higher, because most will be sold to the European Union.

And as with other commercial projects, there are also condensates. This is one of the major revenue sources of the project: it is blended with Azerbaijan’s light oil and exported.

The transit fee payable for SD2 gas through Turkey is $70/’000 m³. Turkey also plans to add $5.95 as tax. So Turkey is one of biggest winners of this project – not only in terms of transit fees and taxes alongside gas imports; but Botas has a 30% share in the TransAnatolian Pipeline (Tanap).

Tanap’s CEO Saltuk Duzyol has said that Turkish companies have already been awarded service contracts to the tune of $3.6bn. Tanap’s other shareholders are Socar (58%) and BP (12%).

Coming to the European section of SGC (TAP) the participant states do not receive a transit fee, though recently local media reported that Greece is hoping to extract more taxes from TAP shareholders, including BP (20%), Azerbaijan’s SGCC (20%), Snam (20%), Enagas (16%), Fluxys (19%) and Swiss Axpo (5%).

But this is the first stage, for 10bn m³/yr. Bringing the project to its final capacity of 20bn m³/yr is more complicated – always assuming it is welcomed in Italy, whose new government has just decided to review the project. Socar VP Elshad Nasirov told NGW that EU has exempted TAP from the Third Energy Package, but that excludes the extension stage.

Potential sources of that gas are Russia – when TurkStream’s second, 15.75bn m3/yr line becomes operational – and also gas from north Iraq. Other sources of gas such as Iran or Turkmenistan are not feasible, because of the distance it would have to travel, making it very expensive. No European clients have been in talks on gas purchase as of now.

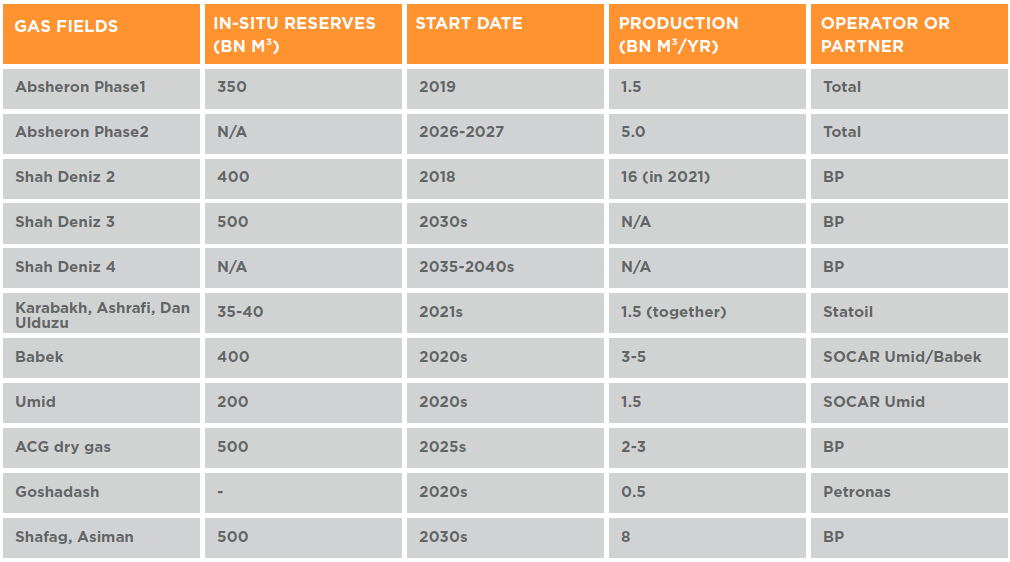

For now, beside SD3, Azerbaijan also has other gas fields for export in next decade, which can help SGC to reach its final capacity theoretically without much dependence on other suppliers. But Russian gas is still a contender for TAP, with the route of the pipeline still not finally decided. If the second leg of TurkStream were to go straight to Bulgaria under the Black Sea, that would limit its ability to supply TAP, which is further south.

Azeri Gas Projects, Under Development and Planned

Source: Socar, industry sources

Dalga Khatinoglu, Ilham Shaban

Cover photo credit: TAP