[NGW Magazine] Managing the Energy Transition

The FT held a summit on energy transition strategies in June, offering a platform for speakers to consider the major trends and the changes affecting the industry and providing a glimpse of what might come.

Oil companies are moving into the renewable area, using a mix of fossil and solar and wind to secure the best return on their commodities. At the same time, they have a vested interest in securing a market for their fossil fuels. On the other hand, the renewables and alternative energy camp recognise that they cannot yet offer a viable alternative.

Kingsmill Bond from Carbon Tracker, John Constable from New Renewables Foundation and Philip Lambert, the CEO of energy advisory Lambert Energy Advisory put forward strong arguments about the future of fossil fuels and renewables at the FT summit in London June 14.

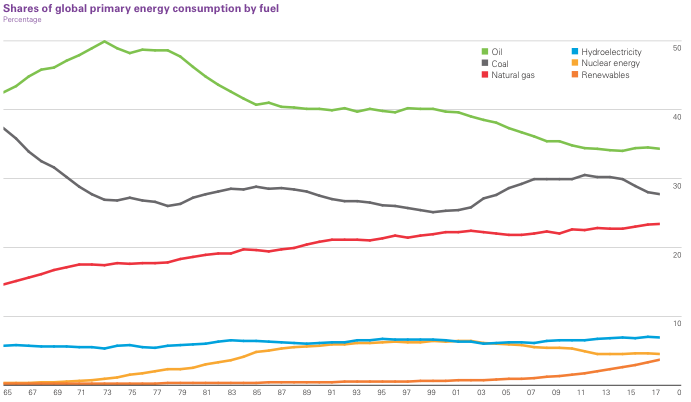

Demonising oil and gas, as some clean energy activists do, ignores the impracticality of using renewables. Apart from their higher cost, they also lack scale and thermal density, and even after more than 20 years of subsidies their penetration is low, if growing, accounting for only 3.6% of global primary energy in 2017 (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Shares of global primary energy by fuel

Credit: BP

However, as the costs of disruptive new technology go down, growth becomes exponential – this includes wind, solar and batteries. Incumbents deny new technology at their peril and markets react to peaks, especially when within 5% to 10% of a perceived ‘peak’.

Divesting from fossil fuels now is not wise. The more effective and pragmatic way forward to reduce carbon emissions may be through a realistic global carbon tax.

Taking this up, BP CFO Brian Gilvary said that transitions take long and overlap – coal is still here. Global progress in the last 200 years has inextricably been linked to energy. He argued: “We must be able to meet the increasing demand for energy reliably. During the next 20 years we will need 35% more energy as global prosperity increases.”

Technology enables energy to be provided at scale, on-demand and at affordable levels. Gilvary stressed that “It is not a race to renewables – it is a race to lower emissions.” He added: “We are not trying to convert BP into a renewable business: what we are trying to do is supply energy with a much lower carbon footprint.

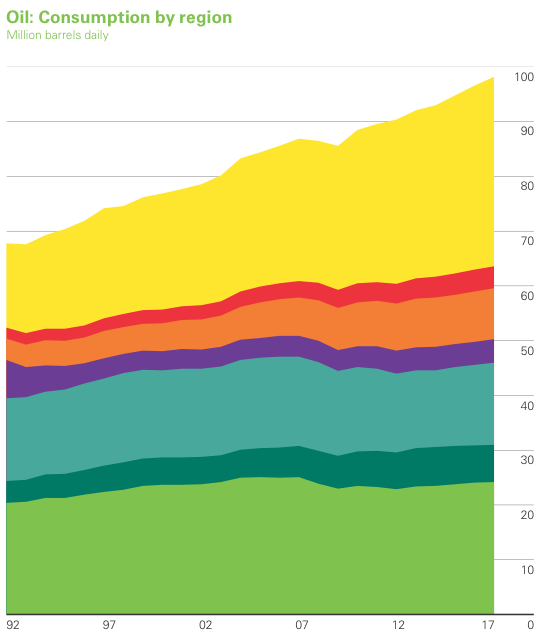

BP does not see under-investment becoming an issue yet, he said, adding that there are no signs of oil shortage after the recent drop in spending. As chief economist Spencer Dale said at the launch of the Statistical Review of World Energy early in June: “The constant in oil market in recent years has been the strength of demand growth. And that continued in 2017, with oil demand growing by 1.7mn b/d, similar to that seen in 2016, and significantly greater than the 10-year average of around 1.1mn b/d.” (Figure 2.) Technology is enabling better recovery of oil and gas and lower decline rates, at lower costs.

Figure 2: Global oil demand

Credit: BP

BP believes that a global carbon price set by the market is crucial in the drive to lower emissions. The success in the UK during the last few years strongly supports this. The company has been factoring a carbon price into its project costing since 2007.

BP’s reserves-to-production index averages 14 years and the capital cycle averages half that. If BP stops investing tomorrow in new production, it will have 14 years of production left. As a result, BP does not expect its assets to be stranded. And neither does it expect global oil supply shortages in the coming years because of reduced investment. Similar numbers apply to other IOCs.

BP accepts that a tenth of investors do not want to continue investing in fossil fuels, but there also a tenth who do, leaving four fifths undecided. BP and other international oil companies (IOCs) are focusing on cultivating optionality within their portfolios, to convince these investors that they can thrive in the energy transition.

Concluding, Gilvary said “We are looking to invest in renewable and low-carbon opportunities. But the difference from the past is that it will be anchored to our existing businesses.

Eni CEO Claudio Descalzi in his speech acknowledged that the energy industry is facing big challenges and different dynamics. The energy mix is changing, with renewables making increasing inroads. But renewables face the challenge of intermittency making them unreliable. In the US, market-driven changes have meant more gas is used, with a strong impact on reducing carbon emissions, and IOCs are responding to this.

Claudio Descalzi, CEO Eni, addressing the summit (Credit: Charles Ellinas)

About two-thirds of Eni’s production is gas and it has been taking measures to reduce methane emissions and flaring. The company has also been using the latest technology to upgrade its refineries and chemical plants, with emphasis on improved efficiency, the reduction of its carbon footprint and waste and lower costs. Descalzi pointed out that in addition to “changing the energy mix, we also need to change our development model. We have to transform waste into energy.”

Eni is also promoting the development of renewable energies and is, for example, investing resources in nuclear fusion technology, which, Descalzi said, may become available in 10 to 15 years.

Unquestionably the energy industry is changing. It is going through a major transition, but in doing so it is time for a reality check – where does it go from here?

A reality check

Energy markets are being transformed through decarbonisation, decentralisation and digitalisation. The costs of renewables, wind and solar are plummeting. Energy efficiency is improving and new technologies are making a difference. Change is underway, but there are many challenges ahead.

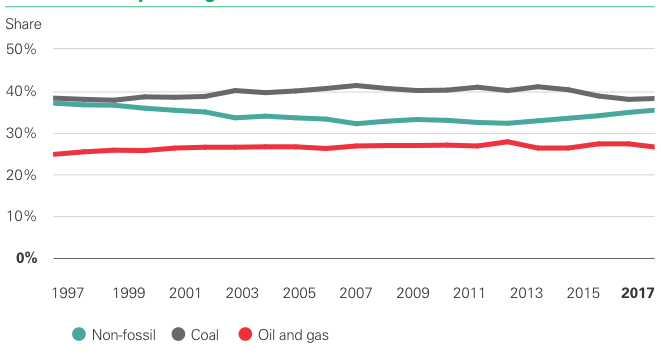

One-time CEO of BP, and now the chairman of Glencore, Tony Hayward agreed that there is a need for a reality check, but he argued that the real question should be “What transition?” He pointed out that according to BP’s latest energy statistical review, over the last 20 years there has been no significant change in the global power energy mix (Figure 3). As Dale said earlier in June, 20 years ago the share of electricity generated globally by coal-fired plants was 38%. It was still 38% in 2017.

Figure 3: Fuel shares in power generation

Credit: BP

It looks more like normal evolution of energy sources over a long time period rather than short-term energy transition. In Europe energy demand is not growing and policy is driving renewables and the transition. By 2050 it is possible that renewables could provide up to half of Europe’s energy.

But energy demand is and will be increasing in developing countries as their prosperity improves. Outside Europe the rate of penetration of renewables faces challenges. It is being overpowered by the growth in global energy demand.

China’s coal production increased last year by 3.5% and consumption by 0.5% as its economy carried on growing. Apart from dealing with intermittency, the world needs policy direction to drive renewables, but also decarbonisation of fossil fuels.

Hayward concluded by saying: “In my view the transition has to be at least as much about how we burn fossil fuels as it is about new sources of energy. We’ve got to get to the point where there is much more focus and support and policy directed at driving a lower carbon intensity of fossil fuels if we are going to get anywhere close to climate targets.”

The CEO of CLP Holdings, a vertically-integrated Asian utility, Richard Lancaster, took this up further. China is addressing the problem of city pollution, but it still needs coal. In order to reduce carbon emissions from coal-fired power generation China introduced new stringent regulations and it is building high efficiency coal plants.

These regulations are much tighter than in Europe, to the extent that most coal plants in Europe would not pass them. India is investing in solar but still needs coal and coal demand will continue rising for years to come.

Despite the growth of renewables as a low-cost source of electricity, emerging economies are still investing in coal to ensure 24-hour supply and to support industrial development, but also because of its low cost.

The chair of the board at the Climate Group, Joan MacNaughton, considered the increase in coal consumption in China in 2017 a blip. She said China is delivering on its nationally determined contributions (NDCs) made in accordance with the Paris Agreement, but she also said it is going to be a long haul and policy without action is meaningless.

The Climate Action Tracker considers China’s NDCs to 2030 to be ‘highly insufficient’ as they are not ambitious enough to limit warming to 2°C. These targets, which include a 58% share of coal in national energy consumption by 2020, are consistent with temperature increases between 3°C and 4°C.

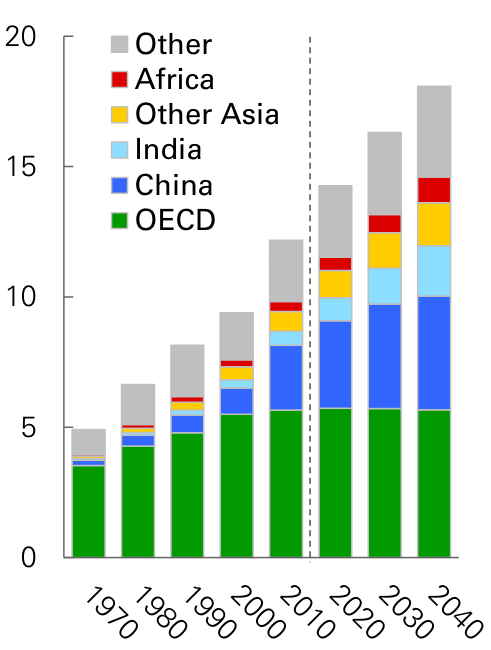

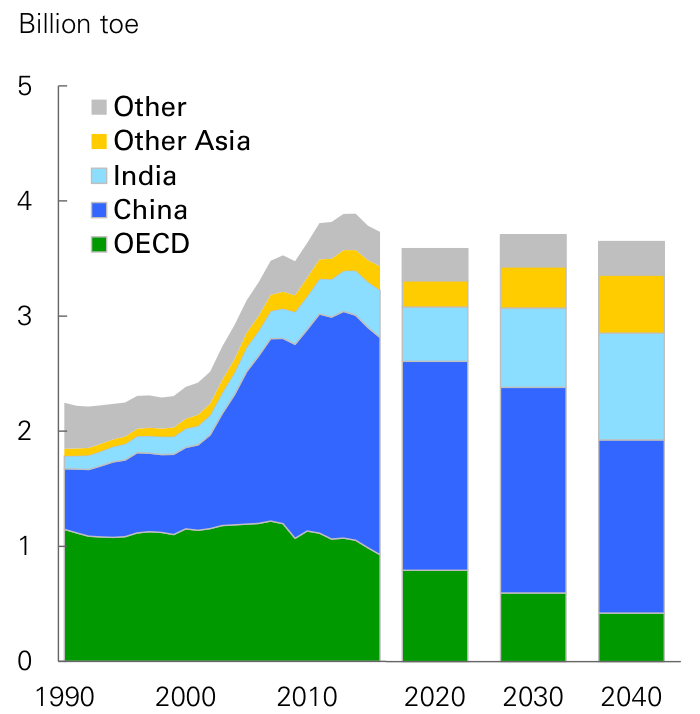

A professor at Kings Policy Institute at Kings College London, Nick Butler, said that energy is changing geography. Future energy demand growth will be led by Asia. By 2040 China will be consuming a quarter of the world’s primary energy, as much as the rest of Asia (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Global primary energy demand (bn tons oil equivalent)

Coal is not dead in India or China, or in the rest of Asia (Figure 5). China will continue to use coal for security reasons, and there and elsewhere economics will increasingly prioritise domestically produced energy, which includes coal.

Figure 5: Coal demand by region

Credit: BP

Butler went on to say that the growth of renewables is changing the global energy market. The world has entered an era of plenty in terms of energy and this is leading to changing market structures.

The old models are out of date. Despite the sharp growth in global demand for electricity, a recent McKinsey analysis of 50 major publicly listed utilities from Asia, Europe, and North America showed average total cumulative returns to shareholders of about 1% from 2007 to 2017, compared with an average of 55% for other listed companies. Utility company business models are either changing or in need to adapt to rapidly changing market structures. Those most capable of adapting will survive.

Bridging the renewables gap

Battery storage is already smoothing supply and demand, but utility-scale storage is needed to bridge the gap between intermittent renewables and 24/7 reliability. It is slated to be the next big disruption to take the energy industry by storm. But it has its own challenges.

Simec Group's CEO of energy and mining Jay Hambro said that storage and renewables will be the future model. For brief periods of need, battery storage is gaining a foothold. But utility-scale, reliable storage has some way to go. However, pumped storage is being used successfully in mining in Australia and is being rolled out in South Africa and South America.

Ultimately what drives energy storage is economics, not policy. Storing energy to bridge seasonal demand at utility scale is still a challenge, but without it, migration to high levels of renewables will remain problematic.

The renewables’ resource risk

A clean energy future is intensive in terms of materials and energy. Some materials, such as cobalt, are concentrated in a small number of vulnerable countries with questionable labour and human rights practices. If access to these materials is not properly managed, they could disrupt efforts to meet critical climate objectives.

A researcher at Amnesty International, Mark Dummet, said companies need to respect human rights and must resource cobalt responsibly from countries such as the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC).

Parts of DRC that are being mined are becoming highly polluted. He argued that “these countries should not pay the price for the shift to renewables.“

Dummett said that investors are increasingly questioning environmental, ethical and societal compliance issues. Industry needs cobalt from DRC and DRC needs the income, but it must be done ethically.

Portfolio manager at Investec Asset Management, George Cheveley, told the conference: “One of the things we start to think about is, should we actually worry about whether there will be enough resources to supply battery materials for electric vehicles for everybody to own one, just as we own gasoline-fuelled vehicles?”

How do you factor such risks in energy investment? He suggested that the sustainable use of materials may mean giving up on individual ownership of vehicles and moving to autonomous vehicles. This could increase vehicle utilisation rates from less than 10% now to 95%.

The role of fossil fuels in a decarbonised world

The demise of coal has long been predicted, but it stubbornly remains at high levels, with little signs of change. Peak oil is supposed to be round the corner, but so far annual growth in oil consumption remains high. International oil companies (IOCs) hope that during transition natural gas will be the answer.

Felix Lerch, UK chairman Uniper, said that his company provides a bridge into the energy future: renewables partnered with a strong natural gas portfolio. Gas is the cleanest fossil fuel and is flexible.

Transition will take time and in the meanwhile decarbonisation of energy generation must be achieved in an ‘orderly’ way.

Environmental actions need to be balanced with security and reliability of supply and economics and carbon capture and storage (CCS) does not do this at present. On the other hand, modern CCGTs balance the above and enable gas to deal with intermittency problems efficiently, economically and reliably.

Are investors in fossil fuels doomed?

During the last decade costs of renewables have fallen substantially, to the extent that subsidies will soon become unnecessary. Investments in renewables have been outpacing those in fossil fuels. Is it becoming inevitable that investors in fossil fuels are doomed?

That was not the view even of proponents of a speedier switch to renewables. A partner at investment firm Foresight Group, Carly Magee, who looks at the renewable energy infrastructure sector, clarified: “We are not saying: let’s give up on all fossil fuels tomorrow. It definitely is a transition.” Nobody is calling for an immediate energy revolution.”

Emerging opportunities

The transformation of the energy industry continues. Fossil fuel companies, renewables companies and utilities are pursuing new business models to ensure sustainability and profitability in the future. Such models aim to bridge current and prospective revenue gaps, addressing changing customer needs, exploiting new technology.

These include “a connected battery network that can provide power when and where needed when the sun is not shining – a virtual power plant,” said Felix Dembski, vice-president strategy at sonnen. It can also move power generated from renewable sources from times when renewable energy is available but demand is low to times when demand is high and it can be used as a reliable backup supply.

BP's Roy Williamson said that the company is investing in ultra-fast charging. “We believe ultra-fast charging is critical to the widespread adoption of electric vehicles. That’s why we have partnered with companies such as StoreDot, a company that is developing batteries that can be charged in five minutes or less.”

And TAE Technologies CEO Steve Specker said the company is developing fusion technology. It expects to have a prototype by mid-2020s. If it is successful, commercialisation could be achieved by early 2030s.

In his view none of the currently available technologies can lead to elimination of carbon emissions by 2050 – but fusion can. If fusion fails, then advanced nuclear fission may be the way to achieve decarbonisation at the required scale. But Specker believes “fusion will power the world.”

Charles Ellinas

_f1920x300q80.jpg)