[NGW Magazine] Powering Indonesia

The executive president of Indonesian state PT Nusantara Regas Tammy Meidharma talked to NGW about his country's widening gas supply-demand imbalance and the critical role played by LNG, and other energy sources too.

NGW had the opportunity to meet Tammy Meidharma to ask him about LNG supply and regasification in Indonesia, and the country's gas supply-demand balance generally, its growing gas deficit, the complexity of delivering gas to its small islands and the rising use of small scale LNG shipping and floating storage and regasification units (FSRUs) to achieve this.

NGW: Indonesia is fast turning from an exporter of LNG into an importer owing to the rapid increase in domestic demand. How widespread is the use of gas in Indonesia? Can you tell us more about this and about what is driving this growing demand?

TM: As part of efforts to reduce fuel bills and environmental pollution, the Indonesian government is committed to replace diesel fuel with natural gas in electricity generation and industrial production to the greatest extent possible. Indonesia has committed to reduce emissions by 29% by 2030.

This objective is leading to the reduction of government subsidy for electricity. In addition, an optimised LNG supply chain could lead to cheaper energy. The energy cost saving is to be allocated to infrastructure projects, to support the economic development of Indonesia.

Other aims are to support the government programmes for gas in transportation, for households, small consumers and industry. The government also wants to increase oil and gas production as well. Since Indonesia’s economy has started to expand, the drive is to adjust the country’s energy supply to match the rising demand.

NGW: How will the gas supply-demand deficit be covered?

TM: Most centres of Indonesian gas production are offshore. Among the largest are Bontang (East Kalimantan) and Tangguh (Papua). These fields meet most of the rising demand for gas in Indonesia. Additional production is also expected from the Tangguh third LNG process train, planned to start operations in 2020, and from the Masela block at a later stage.

But even then, Indonesia will require some gas imports to cover rising domestic demand. The main reasons are that existing gas-fields are maturing; and developing the country’s proven reserves is facing challenges.

In anticipation of this future domestic demand growth, the Indonesian national energy company Pertamina has contracted LNG imports. It has already signed three long-term sale and purchase agreements (SPAs): one with Cheniere; one with ExxonMobil; and one with Woodside, covering an aggregate 4mn mt/yr and starting in 2018.

NGW: With over 17,000 islands, how do you get the gas where it is needed, especially for power generation? You said at Flame that small scale LNG combined with FSRUs is the best option. Can you tell us why and why not pipelines?

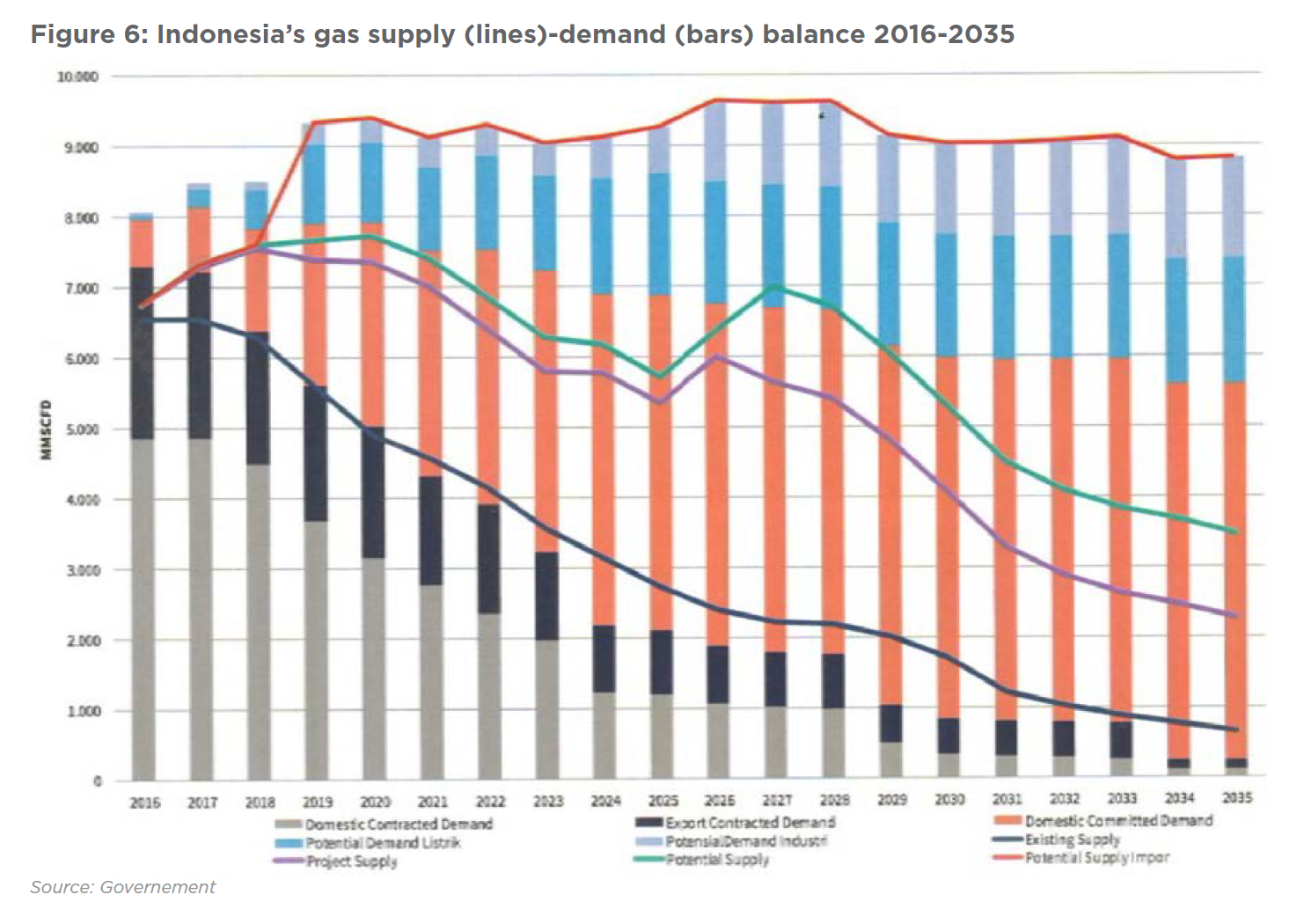

TM: The delivery of gas from the resource-rich eastern part of the archipelago to the main western markets on the islands of Java and Sumatra represents a major challenge (Figure 1). LNG offers the best solution to this logistics problem in a country of 17,000 islands that stretch over 5,100 km from east to west and 1,800 km north to south. LNG offers a flexible solution to many of the nation’s unique energy supply logistics challenges.

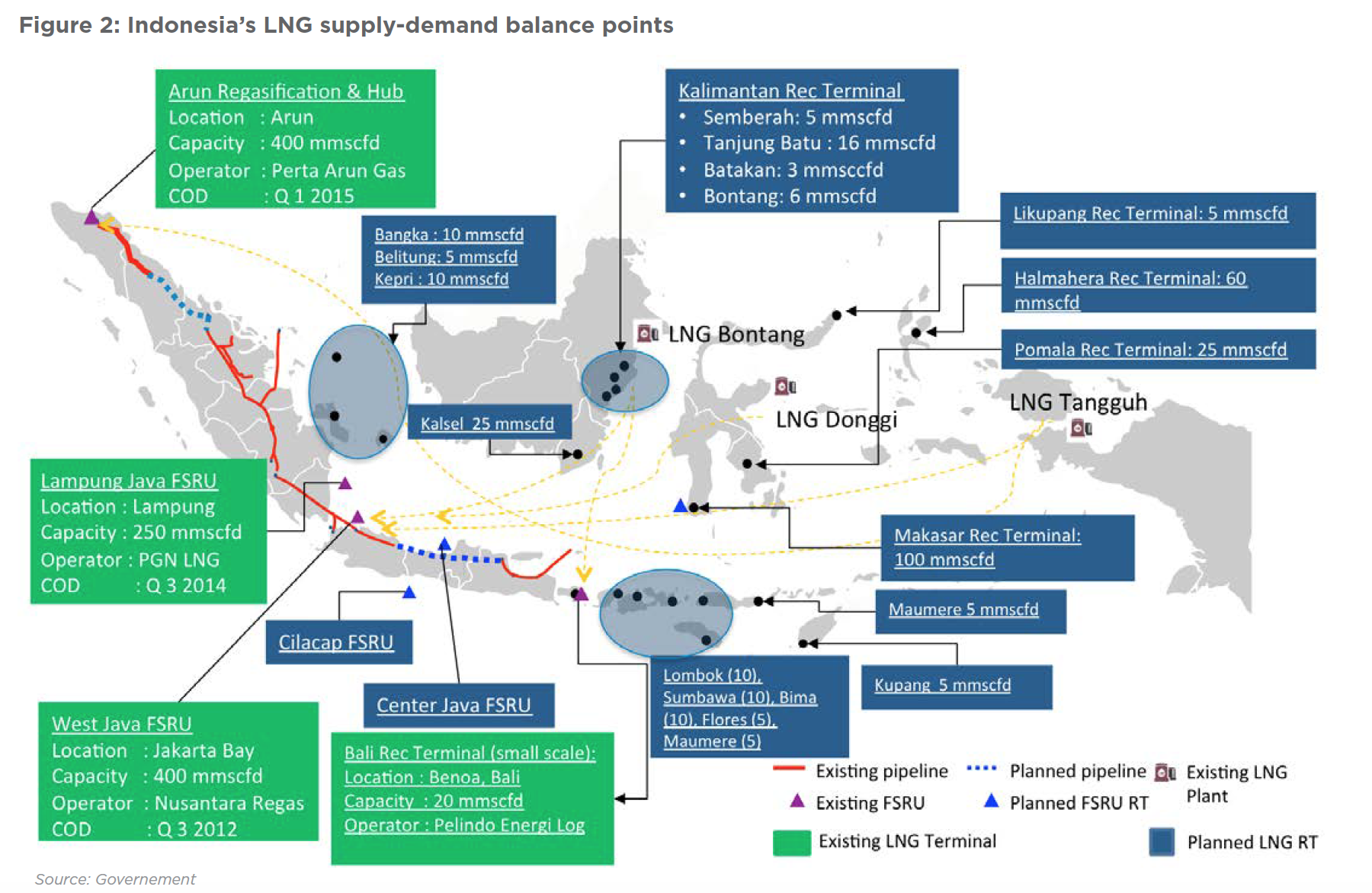

Pipeline distribution is possible where the population and demand are large enough, such as Sumatra and Java. Otherwise it is uneconomical. The Bontang Arun hub, Lampung FSRU and West Java FSRU are being used to meet the needs of surrounding areas.

Pipeline distribution is possible where the population and demand are large enough, such as Sumatra and Java. Otherwise it is uneconomical. The Bontang Arun hub, Lampung FSRU and West Java FSRU are being used to meet the needs of surrounding areas.

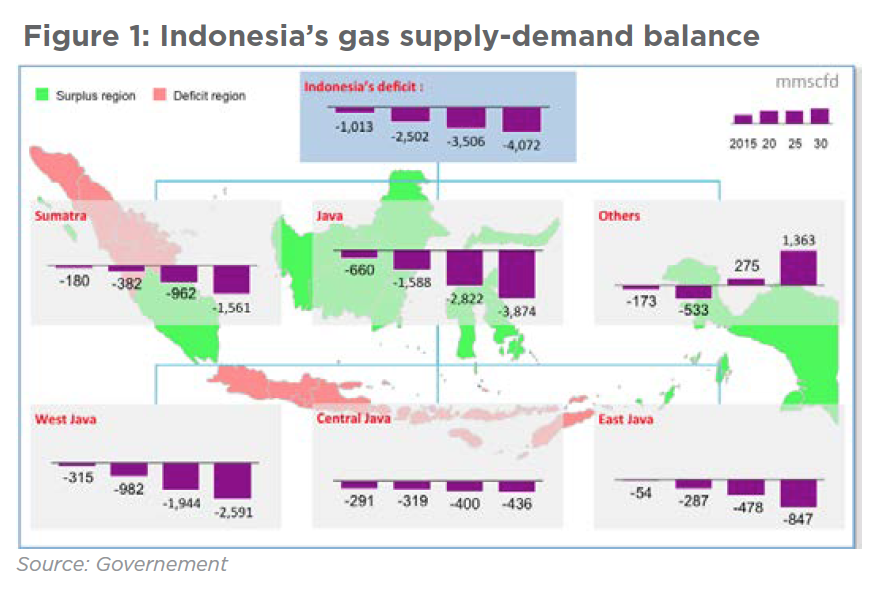

Small scale LNG combined with existing and new FSRUs is the best option to ensure that natural gas can be easily transferred to the end-user (Figure 2). Distribution by tanker is easier than by pipeline because major gas reserves are offshore or distant from large gas demand centres.

NGW: In past presentations you said that in order to integrate gas supply and demand among regions, it is necessary to accelerate gas infrastructure development, not only at strategic locations but also to Indonesia’s scattered islands. Can you describe the magnitude of the problem?

NGW: In past presentations you said that in order to integrate gas supply and demand among regions, it is necessary to accelerate gas infrastructure development, not only at strategic locations but also to Indonesia’s scattered islands. Can you describe the magnitude of the problem?

TM: The government’s target is to increase the use of natural gas in power generation. This is the responsibility of state-owned PLN, which has exclusive powers over the transmission, distribution and supply of electricity to the public, and will require further development of infrastructure.

The eastern part of Indonesia has surplus gas, while the west and south parts are in deficit, so to cope with the large amount of gas demand in western Indonesia, adequate gas infrastructure within the region is needed. The development of small regasification facilities is now becoming important in Indonesia, as an archipelagic country, to distribute energy across the archipelago.

In the natural gas business we have to consider the distance and volume to be distributed to the consumer, whether it is with pipelines, or compressed or liquefied natural gas. LNG is the most economically viable in terms of reaching buyers within thousands of kilometres, by using large ships designed specifically to transport LNG.

NGW: Is there infrastructure to support this and if not, what is being proposed?

TM: Existing energy infrastructure has limitations. Due to economic challenges, at present priority is being given to improving transportation infrastructure, with energy being next.

The provision of natural gas in the country up to now has been met by higher indigenous natural gas production. Infrastructure facilities for the distribution of natural gas include supply through city gas networks for households and natural gas filling stations for transportation.

Indonesia’s gas infrastructure, including LNG plants, gas pipelines, FSRUs and regasification facilities, is described in Figure 3. The country plans to build another FSRU to meet its energy needs.

For scattered islands in eastern Indonesia, the optimal chain covers a floating regasification terminal with point-to-point LNG transportation to scattered small onshore terminals.

For scattered islands in eastern Indonesia, the optimal chain covers a floating regasification terminal with point-to-point LNG transportation to scattered small onshore terminals.

NGW: Can you describe the complete supply chain and its operation?

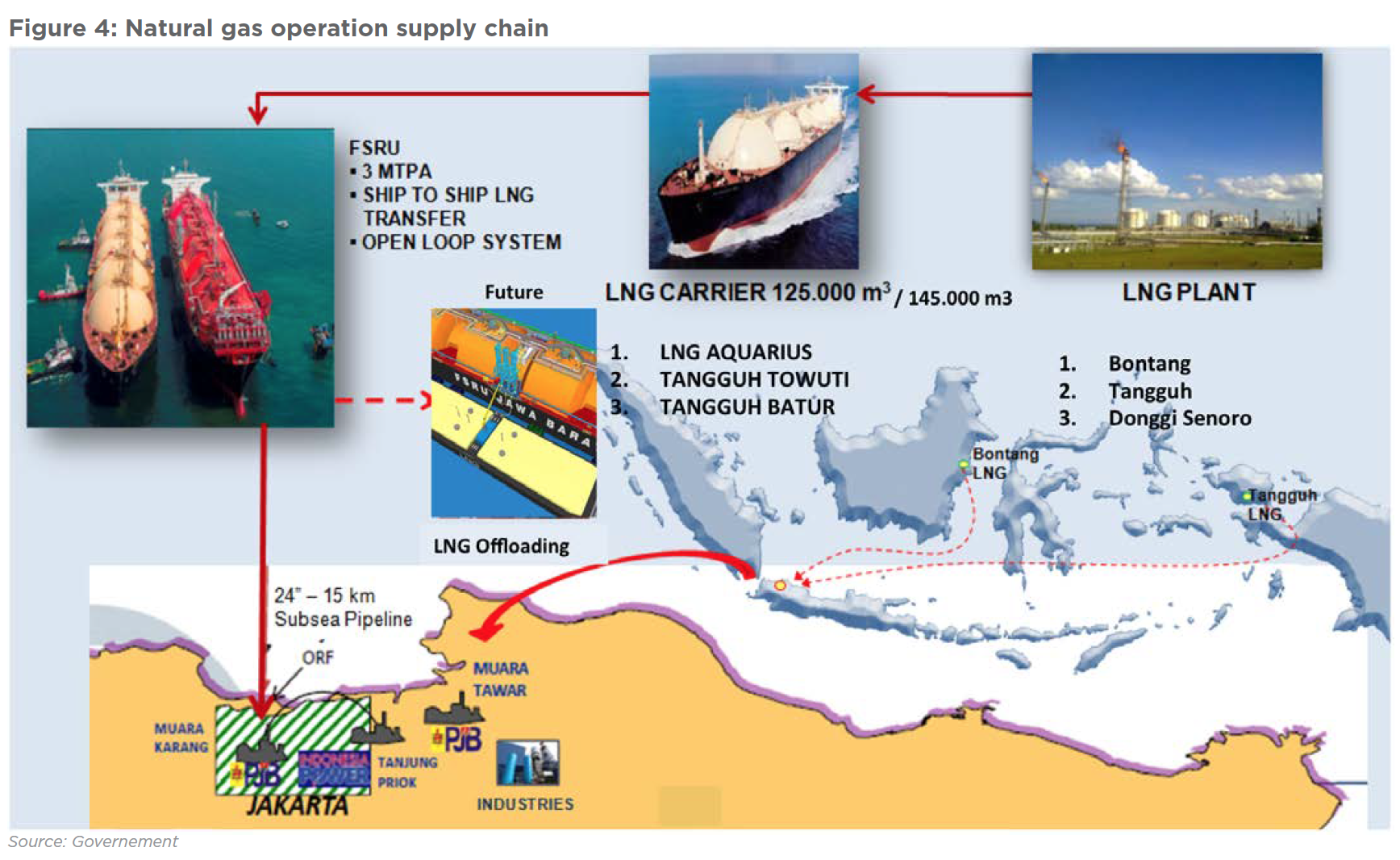

TM: Our LNG value chain starts from an exploration and production facility, where natural gas is supplied to liquefaction plant. LNG is then loaded into the LNG carrier to be supplied to Nusantara Regas Satu (FSRU Jawa Barat) which is operated by Golar. It entered service in Jakarta Bay in 2012. On this FSRU, LNG is regasified and delivered through our 24-inch sub-sea transmission pipeline to onshore receiving facilities (ORF) in Muara Karang (Figure 4).

ORF consists of five distribution lines to deliver compressed gas to PLN Muara Karang, PLN Muara Karang, PLN Tanjung Priok, PGN West Java Distribution and PLN Muara Tawar through the Pertagas Muara Karang-Muara Tawar pipeline. Gas is then distributed to buyers on the island.

ORF consists of five distribution lines to deliver compressed gas to PLN Muara Karang, PLN Muara Karang, PLN Tanjung Priok, PGN West Java Distribution and PLN Muara Tawar through the Pertagas Muara Karang-Muara Tawar pipeline. Gas is then distributed to buyers on the island.

NGW: Given the complexity of LNG import, regasification and distribution of gas, owing to Indonesia’s geographical spread, how do you ensure LNG availability where it is needed?

TM: As I indicated earlier, given Indonesia’s current gas supply-demand balance, some gas imports are needed to meet future needs. This also requires hub terminals to distribute LNG from large vessels to small islands.

Indonesia's government has developed a national energy policy giving direction to national energy management in order to realize energy independence and national energy security to support sustainable national development, including at the local level.

NGW: At the same time Indonesia’s domestic coal demand is also rising. With domestic supplies of coal being plentiful, can LNG imports compete against domestic coal? Why do you think LNG has a future in Indonesia? Is it driven by clean energy considerations and Indonesia’s drive to deliver its pledges for carbon emission reductions?

TM: Gas is mainly allocated for power generation. Base load is still provided by coal, but oil or gas is being used for peak-load needs. But using coal in small islands is not feasible.

As a participating country in global climate change initiatives such as the Kyoto Protocol and the Paris Climate Agreement, in addition to being committed to clean energy and to cut carbon emissions by 29% by 2030, the government committed last year not to build any new coal power plants on Java island, which is home to about two-thirds of Indonesia’s population. Coal will have to be replaced by other fuel sources for power generation, such as gas, renewables and geothermal.

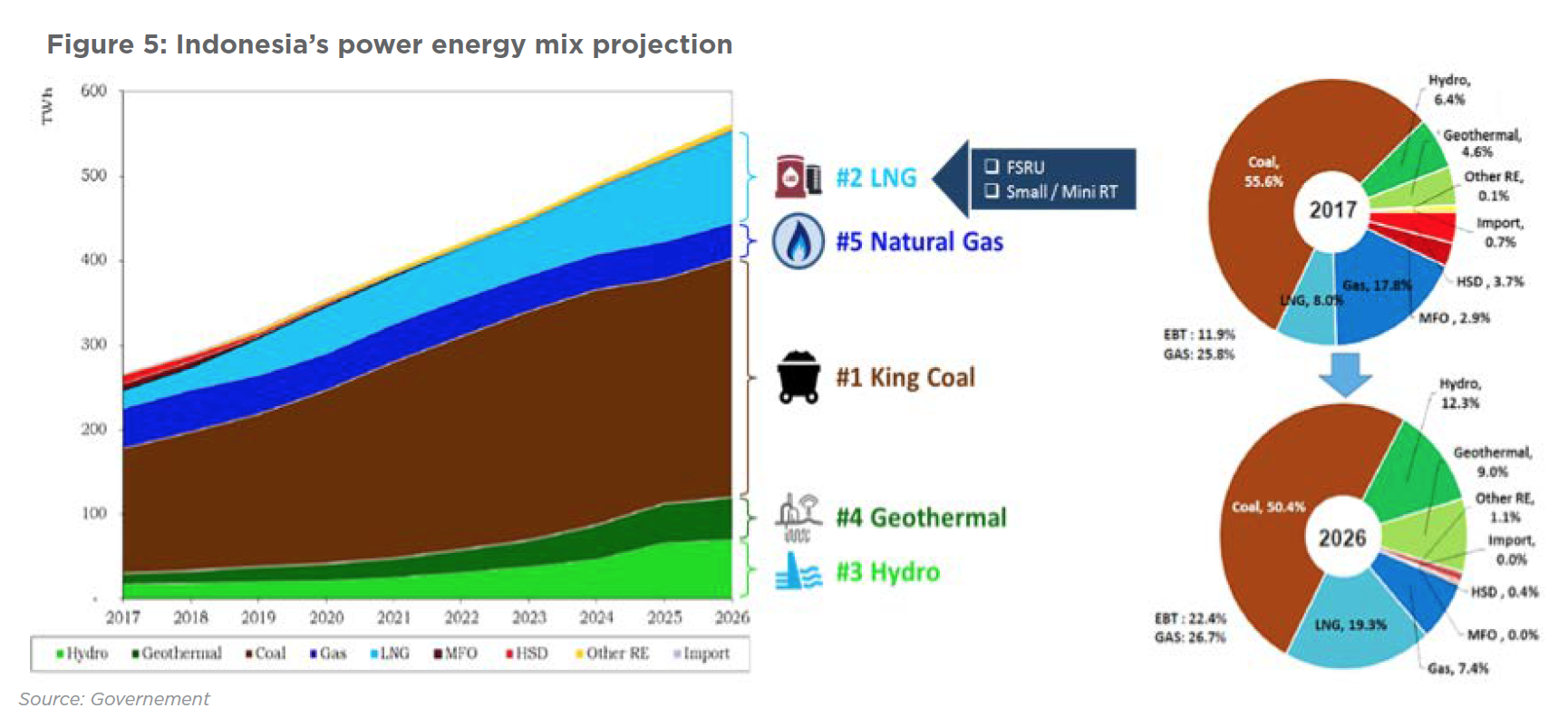

The increase in CO2 emissions comes primarily from steam power plants using coal as fuel. As a result, there will be a time when Indonesia's future will shift from coal to renewable energy to support emission reductions, including hydro and geothermal (Figure 5).

But natural gas is still a major component of energy security in Indonesia, besides being the cleanest fossil fuel - CO2 produced is less than half that from coal.

The government’s policies are focused on ensuring consumer power energy needs. At the same time, Indonesia is also working to improve gas infrastructure, such as the development of FSRUs, in order to receive natural gas supplies from other gas-field alternatives and improve peak shaving capability with gas storage at FSRUs.

NGW: What is the impact of gas prices in comparison to coal prices? How do you see this in the longer term?

TM: In recent months coal prices have risen, as demand from Asian countries such as China, India and Vietnam for Indonesian coal continues to rise. This opens the opportunity for power companies to switch to using natural gas. However, given that global economic activity is still fluctuating, the direction of natural gas or coal prices is still uncertain.

Coal reserves in Indonesia are abundant and national energy resilience may still need to continue relying on coal in the future. In that case clean coal technology in coal mining will be indispensable to reduce emissions produced by using coal. However, in the longer term, restrictions on the use of coal and the need to meet carbon emission targets will increase the cost of using coal, to the benefit of other fuels including natural gas.

NGW: What does the future hold for new gas and LNG developments in Indonesia?

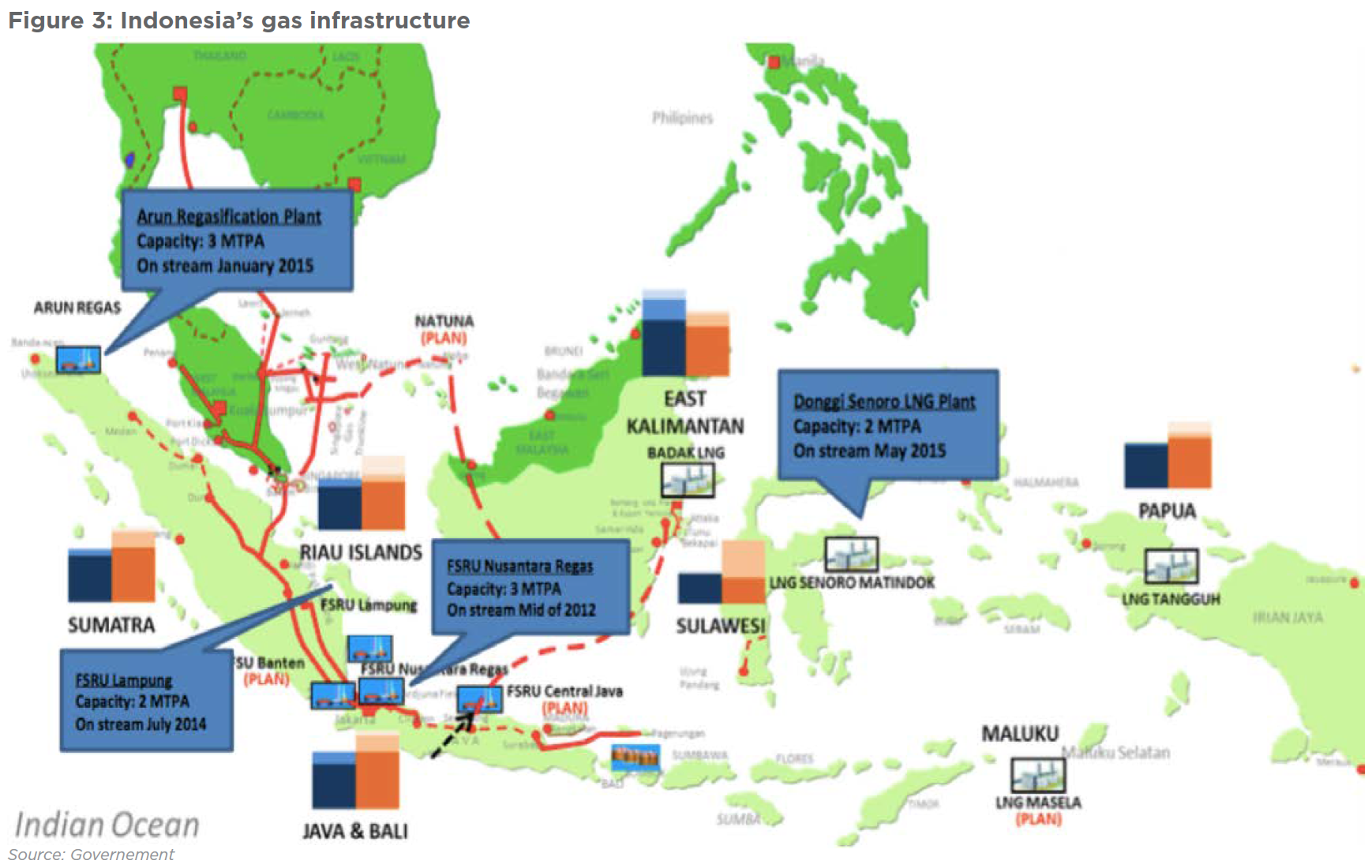

TM: With a population of 260mn and rising, Indonesia is southeast Asia’s largest economy. Electricity demand growth, expected to continue at around 9%/yr (Figure 6), is the highest in the region. In anticipation of the need for LNG imports rising, going forward (Figure 7), the Indonesian government will be establishing guidelines on importing LNG. In the meanwhile, the regulator will continue prioritising domestic LNG for delivery to local buyers.

Indonesia’s gas supply-demand balance is expected to be worsening requiring rising gas imports. Even though demand is expected to stabilise at just over 9bn ft3/d domestic gas supply is expected to start declining after 2020 (Figure 6), as existing gas-fields mature and development of the country’s gas reserves continues to face challenges.

This is despite the fact that gas export commitments will be decreasing over time, to very small levels by 2035. As a result, LNG needs are expected to continue rising, and FSRUs combined with small scale LNG may be the best option to ensure that natural gas is transferred for use by end users in Indonesia’s numerous islands.