[NGW Magazine] Sub-Saharan Africa needs gas

There is the potential to unlock a lot of demand for electricity in sub-Saharan Africa, given the abundant supplies of gas; but one delivery system, Power Africa, is intended to benefit US investors. Governments could also make things easier.

Power Africa, a US government initiative geared towards expanding access to electricity in sub-Saharan Africa, has launched a roadmap to add 16 GW of gas-fired power generation in the region by 2030.

The Gas Roadmap 2030 projects that US companies could invest $175bn in such power projects in sub-Saharan Africa, in turn raising the potential for at least $5bn-worth of US LNG exports to Africa over the next 12 years.

Unveiled during the June 2018 World Gas Conference in Washington DC, the Gas Roadmap dovetails with the 2016 Power Africa Roadmap which spelt out how the public and private sectors could jointly work together to add 30 GW of generation capacity and 60mn new connections by 2030 in Africa. Various energy sources are proposed but, so far and in terms of Power Africa's 2017 annual report and the recently-launched roadmap, natural gas would be the leading energy source.

The annual report says that 7.319 GW of plants had been commissioned up to June 2017, since Power Africa’s launch in 2013, of which 4.315 GW is gas-fired, 1.030 GW is hydro, 810 MW is wind, 628 MW solar, 196 MW heavy fuel oil, 158 MW geothermal, 89 MW biomass and 35 MW diesel. Nineteen gas projects had reached financial close, second to solar with 25 and hydro with 18.

The initiative, set up five years ago under Barack Obama’s US presidency, had according to the latest annual report helped 82 projects worth $14.5bn – giving a total 7.319 GW – reach financial close across sub-Saharan Africa. Of that, 59% of the capacity is gas-fired while three in every four plants run on renewables. More than 2 GW are already operational and 10.25mn connections had been achieved since 2013.

Power Africa is helping to facilitate investment in the electricity grid in Africa and enhancing access to power, according to Zachary Donnenfeld, a senior researcher at Pretoria-based Institute for Security Studies (ISS).

"It really depends on what you consider 'a success,' " he said, referring to Power Africa’s targets. "At the ISS, we use a forecasting model called International Futures or IFs. According to IFs, Africa is forecast to add more than 90mn new connections between 2015 and 2030 in the base case forecast – that is without a significant intervention on electricity. It's not as if Power Africa is aiming to electrify the continent so I think they will hit their target."

Power Africa says two out of three people in sub-Saharan Africa lack access to electricity. The low electrification rate – the lowest of any world region – presents an investment opportunity in an area blessed with a range of potential energy sources. Natural gas is abundant in 14 countries. After decades of production, Nigeria still has the largest amount of gas with about 193 trillion ft³, followed by Mozambique (180 trillion ft³), Tanzania (57 trillion ft³) and Angola (11 trillion ft³) among others.

While Power Africa supports gas-to-power projects across the bloc, the gas roadmap focuses on nine: Cote d'Ivoire, Ghana, Nigeria, Senegal, Angola, Mozambique, South Africa, Kenya and Tanzania.

Eleven countries in the region have gas-to-power plants, with a total current installed capacity of 17.822 GW. Foremost is Nigeria with 12.665 GW, representing 88.9% of that country’s installed generation capacity. But this includes old plants, and plants often constrained by transmission bottlenecks – such that Nigeria’s effective gas-fired generation capacity rarely exceeds 5 GW.

The other ten listed by the Gas Roadmap are Ghana (1.718 GW, 54% of national capacity), Cote d'Ivoire, (973 MW, 51%), Tanzania (748 MW, 46%), Gabon (392 MW, 54%), Congo-Brazzaville (350 MW, 56%), Mozambique (345 MW, 13%), Cameroon (216 MW, 16%), Equatorial Guinea (178 MW, 46%), South Africa (158 MW, 0.34%) and Benin (80 MW, 23%).

"We estimate that these countries hold the potential for around 16 GW of new gas-fired power generation projects through 2030. These focus countries were selected due to their relatively large populations, high gross domestic product, and either because they have local gas resources (in operation or under development) or are planning LNG import projects," says the Gas Roadmap.

Nigeria’s Challenges

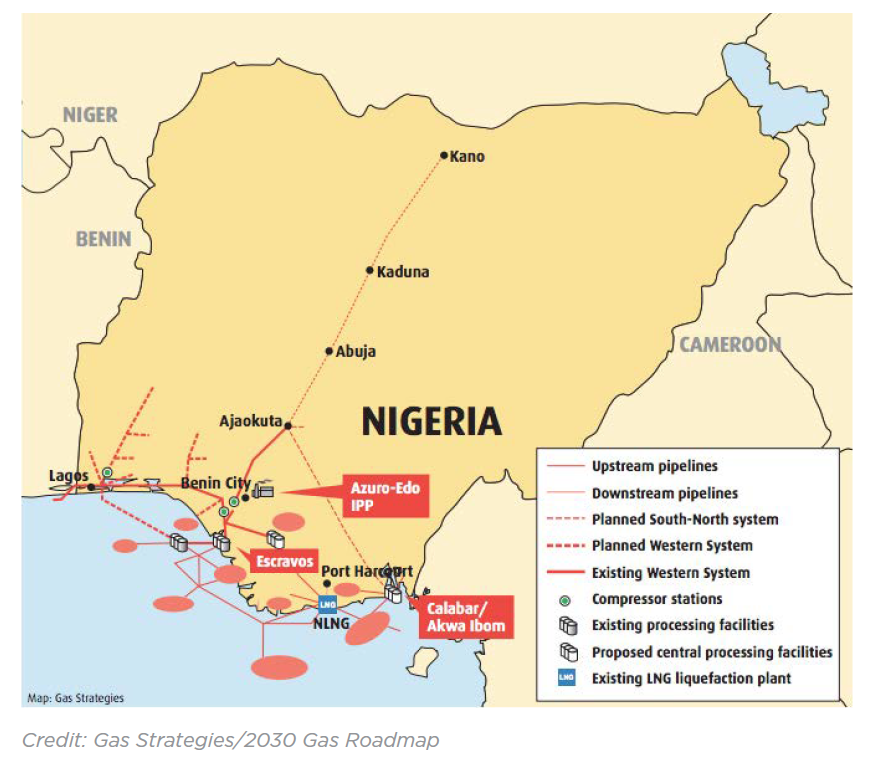

Nigeria is projected to add 4.490 GW of gas-fired capacity through Power Africa-supported projects in the next 12 years, according to the Gas Roadmap, making it a preferred destination for investments under the US programme.

But NJ Ayuk, chief executive of pan-African law firm Centurion Law Group, said that Nigeria – sub-Saharan Africa’s largest economy – still has a lot to achieve in the power sector.

"Its natural gas sector remains under-developed. Despite all the existing potential for using natural gas for transportation, power generation and other uses, the country suffers from constant, chronic and crippling power outages," wrote Ayuk jointly with energy analyst João Gaspar Marques earlier this year in an opinion piece for South Africa’s Cape Times.

Nigeria on July 10 selected four technical firms to help deliver seven key gas infrastructure projects that it hopes will let enough gas flow by 2020 to generate 15 GW of power. But it is a huge ask – requiring not just large investments by both the state but also upstream majors – at a time when political uncertainty is growing ahead of the February 2019 presidential elections. The signs are not promising: for the past year, Nigeria has made scant progress with a similar project, the strategic south-north 614-km ‘AKK’ gas pipeline.

In Tanzania, Power Africa is supporting natural gas projects to install 670 MW at Kinyerezi – with half that already online – while a total 1,170 MW is forecast to be installed nationwide by 2030. But another US gas-fired plant owner Symbion is locked in a legal dispute with the new populist government. The latter has also already upset other mining and upstream gas investors.

In neighbouring Mozambique, the 40-MW Kuvaninga project was commissioned in July 2017 but only after a two-year delay. In Ghana, financial close for the Amandi Energy plant was achieved in December 2016 and the facility is earmarked for operation in December 2019; that $552mn, 200-MW project will initially run on oil and later from natural gas obtained from an offshore field. The Eni-operated OCTP field recently became the third large offshore Ghanaian oilfield to start producing gas, following the Tullow-operated Jubilee and TEN fields, all of which are improving gas supplies to generators.

There are some challenges that must be overcome for the natural gas industry to be established in sub-Saharan Africa, the Gas Roadmap acknowledges.

"A fundamental challenge revolves around institutional or structural problems relating to the production, use, or regulation of gas. These challenges focus around opening the market through development of policy or regulation or frameworks for upstream and downstream developments. Interventions may take time to implement and may require significant technical expertise, but could provide a good return on investment as the revamped institutional framework may allow a higher level of certainty for private and public sector investors," it says.

Demand for gas is low, most countries in sub-Saharan Africa have limited or no creditworthy off-takers as well as power grid constraints. To address the grid challenges, Power Africa in March 2018 launched a strategy that focuses on improvement of power transmission and distribution.

Need to Embrace Gas

Power Africa will be instrumental in achieving the foregoing, said ISS’s Donnenfeld. But he adds that the initiative has two key weaknesses: it is geared to prioritise US companies; and it does not include measures to stimulate demand for power. Pricing of the new electricity output, he said, must be affordable.

"The continent should embrace natural gas over coal in large population centres for baseload capacity to attract manufacturing and other industries,” said Donnenfeld, in a remark directed at South Africa which for two years has stalled on a strategic programme to gradually shift its economy away from coal-fired electricity towards new gas-fired plants, backed by LNG imports. The country’s new president Cyril Ramaphosa and his energy minister Jeff Radebe signalled in May they mean to revive that programme, risking a rift with the giant state-run coal-dominated generator Eskom.

“Renewables are already competitive from a price standpoint - as evidenced by China and Germany removing subsidies - but cannot support a large manufacturing or mining sector, so I think gas is a decent substitute until someone is able to resolve the energy storage issue," Donnenfeld said.

A recent report entitled Identifying the roadblocks for Energy Access: A Case Study for Eastern Africa’s Gas, published in May by Saudi-based research centre Kapsarc and partners from the US and Italy, said that despite the abundance of gas in parts of East Africa "the rollout of planned power capacity additions [in the nine countries in the region featured by the report] has been slow, and countries are unlikely to reach their respective capacity targets.”

Tariffs Don’t Cover Costs

“Reasons for the low energy access vary but are tied to mostly the financial capacity of governments, inadequate revenues for utilities, tariffs being lower than costs, and a weak regulatory framework to implement energy policies," adds the Kapsarc report, which was co-authored by Columbia University’s Center on Global Energy Policy (CGEP) and the Fondazione Eni Enrico Mattei.

It notes from countries' own national energy goals that most – Tanzania, Mozambique, Uganda, Kenya, South Africa – plan to expand gas-fired generation as part of a mix, with the others putting the emphasis more on expanding renewables (Ethiopia) or renewables plus biogas (Rwanda, Burundi, Malawi - but the latter also increasing coal-generation).

"Installing prepaid meters would potentially improve utility revenues by guaranteeing a flow of payment from consumers" to the investors in the system, and the report claims a degree of success in rollout of such meters in Malawi and Mozambique: "A happy medium needs to be struck between offering affordable electricity tariffs to consumers, and profits for state utilities and Independent Power Producers.”

The issue of tariffs being insufficient to cover costs, let alone investment, is picked up in the International Energy Agency’s World Energy Investment 2018 report (WEI), released July 17. “National utilities in most other countries in sub-Saharan Africa remain far from cost recovery,” the IEA said, citing a 2016 World Bank study which found that 40% of their persistent “quasi-fiscal deficits” were attributable to under-pricing of electricity, 30% to high network losses and 20% to inadequate bill collection.

The latest IEA report more broadly finds that, of the estimated $1.8bn invested globally in energy, just 5% (or $84bn) went to the whole of Africa – which included Egypt where several upstream gas and gas-fired power plants have been under development.

Of that $84bn, an estimated $37bn – so 44% – was invested Africa-wide in upstream oil and gas (much of it on export-oriented projects). That left just $15bn invested on the continent’s thermal generation plants (gas, oil or coal), $14bn on its downstream oil and gas, and just $9bn on power networks across Africa for its close to 1.3bn inhabitants.