[NGW Magazine] Interview: Europe needs nuclear

Energy market transition: NGW interviewed Tim Yeo, now chairman of the New Nuclear Watch Europe Institute (NNWE) and formerly chair of the UK parliamentary Energy and Climate Change Select Committee; and minister for the environment.

NGW took the opportunity to talk to Tim Yeo about energy transition, its impact on Europe and the role of New Nuclear Watch Europe (NNWE) at an energy conference in Thessaloniki where he gave a presentation.

NNWE was established in 2014 as a consortium of European, Asian and American nuclear energy companies who share a conviction that nuclear energy is an essential part of the global energy mix. Can you tell us more about this and exactly what is the role of the Institute?

NNWE exists to encourage the development of new nuclear energy plants because of its conviction that nuclear energy is an essential part of the global energy mix. It is necessary to decarbonise the electricity generation completely by 2050 if dangerous, irreversible climate change is to be avoided. This goal can only be reached with a substantial contribution from nuclear energy, which is the only low carbon generator of large-scale dispatchable baseload power.

‘New nuclear’ is a generic term for a new generation of small-scale nuclear power plants, including the use of small modular reactors, which are an affordable alternative to large-scale nuclear reactors. These are expected to become part of the future of the nuclear industry.

NNWI promotes its views through the publication of reports, through its website, by attendance at international conferences and by publication of articles.

At the conference you spoke about the need for and urgency to decarbonise. Can you expand on the reasons, particularly with regards to Europe and especially southeast Europe.

Southeast Europe is more dependent on fossil fuels than the rest of the European Union. The EU has rightly set challenging targets to decarbonise electricity generation, by at least 40% by 2030 and with a long-term, 2050, goal of reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 80-95%, when compared with 1990 levels. Concern about climate change is increasing and the pressure on EU member states and on EU accession countries to meet these targets will intensify in the next few years.

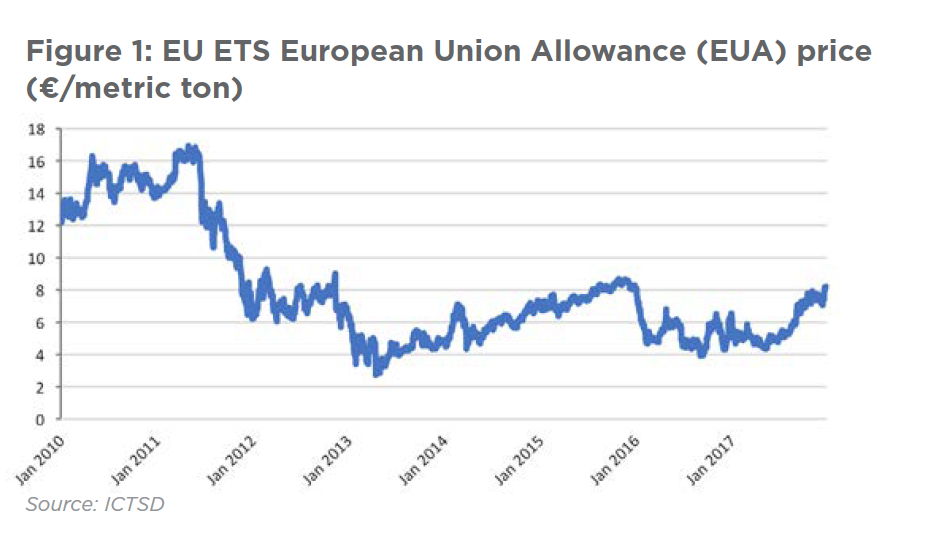

In addition, following last year’s changes to the EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS), the price of carbon allowances has been rising (Figure 1. This will increasingly make consumption of fossil fuels more expensive in the medium term.

What is the impact of energy transition and decarbonisation on Europe’s energy security?

The impact of energy transition and decarbonisation on Europe's energy security will depend on the investment decisions which are made in the next five years. A switch away from fossil fuel dependence to greater use of low carbon energy will improve supply security. However, if gas replaces coal then energy security will be reduced because this will increase Europe's dependence on imported gas. As a result, this may not be a long-term solution.

Replacing fossil fuels with nuclear energy and renewables will ensure that energy transition and decarbonisation improve both security and sustainability.

You spoke about EU’s ETS. What are your views on its effectiveness and why EU member states still feel the need to develop and implement national carbon pricing schemes?

The recent reforms to the EU ETS, including the operation of the Market Stability Reserve, will greatly increase its effectiveness. The number of allowances in the ETS has started to reduce significantly in 2018 and this prospect has already caused a big rise in the price of allowances.

There is no need for individual member states to develop and implement national carbon pricing schemes. However, some member states do so in order to raise revenue[..1] and others because they are keen to ensure a floor carbon price.

You expressed views about Brexit. Can you expand on these with regards to energy transition and energy security.

Brexit should not have a big direct impact on either energy transition or energy security. However, the departure of one of the largest EU member states is not helpful to energy security as there may be a reduction in energy trading between the UK and the rest of the EU.

Consumers in general want reliable, affordable but also greener energy. How can this be provided?

The best way to provide consumers with reliable affordable and greener energy is to accelerate investment in low carbon sources of energy. These low carbon sources include nuclear and renewables. Both have an important role to play. Nuclear power currently provides over 11% of the world’s electricity.

Until large scale, flexible, long-term, affordable electricity storage becomes widely available to overcome intermittency and large scale dispatchability limitations[..2] , nuclear energy is the only source of low carbon dispatchable baseload electricity.

You said that a switch away from fossil fuels to electricity may provide the answers to decarbonisation in the longer term. How can this be achieved?

Fossil fuels, and coal in particular which is the most polluting energy of all, do not provide the basis for any country to enjoy secure, sustainable, affordable energy in the second quarter of the 21st century and beyond.

All countries therefore need to plan to cut substantially and rapidly carbon emissions from their energy systems. This includes cutting the use of fossil fuels by the transport sector and accelerating the introduction of electric vehicles.

Achieving the switch from fossil fuels to electricity requires substantial investment in several forms of low carbon energy, including both nuclear and renewables.

How do you see the contribution of fossil fuels and renewables developing during transition and how do we get to 2050 and decarbonisation without energy disruptions and hiking of costs?

I envisage a rapid phase-out of the use of coal, especially in OECD countries. Gas will have an interim but diminishing role until 2050. By then the electricity generation Industry must eliminate carbon emissions completely. This can be done without disrupting energy supply if sufficient investment takes place in both nuclear energy and renewables.

The cost of many forms of low carbon energy, including nuclear, can be significantly reduced by the consistent pursuit of policies and practices explicitly designed to reduce costs, thus increasing their attractiveness.

Specifically, do you see a role for natural gas during transition?

There will be a role for natural gas during the period of transition. However I do not believe there is any role for natural gas after 2050 unless very low cost carbon capture utilisation and storage technology becomes available.

As the chairman of parliament’s energy and climate committee you said in 2015 that fracking is safe and will benefit UK’s economy and environment. What are your views now?

I am satisfied that, properly regulated, fracking is a safe technology. Over the period to 2050 the UK economy would benefit from using available shale gas reserves because this would reduce gas imports. The environment would also benefit because the emissions from fracking are less than those caused by importing LNG.

How does new nuclear come into energy transition?

New nuclear will help transition to a low carbon energy system provided that it is cost competitive, on a like for like basis, with alternative low carbon sources, ie by taking account of the extra system costs associated with intermittent renewable energy.

You spoke about UK’s Hinkley Point C. As energy minister you got involved in this. What are your views and advice to the UK government?

Hinkley Point C (HPC) will make an important contribution to UK energy needs. My advice to the government is that it should continue supporting the project and help ensure that it is completed in a timely way. .png)

I also believe there are lessons to be learnt from HPC about how new nuclear plant should be financed during the construction phase. In particular government should recognise that the cost of capital has a very big impact on the eventual price of electricity. It is necessary therefore to find ways of minimising that cost.

I support the decision of the UK government to consider taking a direct equity stake in the Wylfa Newydd power station project in Anglesey, being developed by Horizon Nuclear Power.

You advised at the conference that new nuclear has a role to play in southeast Europe. Can you elaborate?

Southeast Europe needs urgently to cut its use of fossil fuels, particularly coal. Hydropower is already close to saturation point in parts of southeast Europe. The quickest and safest way to address the challenge of decarbonisation therefore is to develop new nuclear plant.

Both Russian and Chinese nuclear vendors are interested in developing new capacity in the region. Governments should therefore exploit this situation to obtain the best possible deal. This includes negotiating the right financial package in each country.

Given resistance to nuclear in Europe, safety concerns and perceived high costs, please tell us why you believe new nuclear has a role to play in a future, decarbonised, Europe and how such a role can be achieved.

Not all of Europe is resistant to nuclear. A significant number of European countries are either developing new nuclear plant or seriously considering doing so.

Concerns about nuclear safety are misplaced. The European nuclear industry has an excellent safety record. Safety campaigners should focus their attention on the high level of premature deaths caused by bad air quality.

The cost of the latest new nuclear plant is very competitive with alternative low carbon energy sources such as offshore wind. Significant cost reductions will result from using tried and tested technology, rather than first of a kind, to build new plants.

By focusing on practices designed to cut the cost of new plants and by adopting creative financing solutions for construction costs, nuclear can offer excellent value for money. In the end, improved safety and low cost will ensure that new nuclear has a future in Europe.

It is very hard to see how Europe can decarbonise its energy industry and at the same time avoid jeopardising its energy security unless it embraces new nuclear.