[NGW Magazine] Filling Norway's pipelines

With Russia grabbing the headlines, Norway is often overlooked as a major European gas supplier, accounting for a quarter of the market last year.

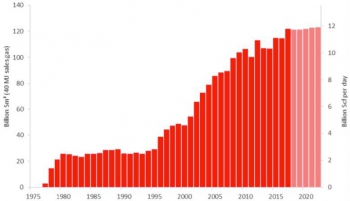

According to the Norwegian Petroleum Directorate (NPD), Norway’s total gas sales in 2017 reached 122bn m³, the highest ever (Figure 1). This beat NPD’s forecast at the start of last year by 6.6% and is due to a number of fields in operation increasing gas production, especially in the largest field Troll (Figure 2), and low summer maintenance. Altogether 85 fields were producing oil and gas on the Norwegian continental shelf in 2017, with 5 new additions.

Figure 1: Actual and forecast Norway gas sales to 2022 (1bn Sm³ 40 MJ gas = 1bn m³ )

Source: NPD

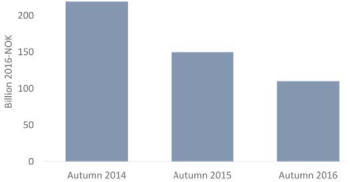

Figure 2: Cost development for selected Norwegian field development projects

Source: NPD

More than 40% of all exports went to terminals in Germany; over 30% to Britain; and the rest was shared between France and Belgium. Output from Troll hit a record in 2017 after the government raised its production cap, and it could pump even more over the next few years. Troll, which began producing gas in 1996, holds 48% of Norway’s remaining gas reserves.

NPD had even better news to announce in January. By 2022 Norway’s gas sales are expected to increase slightly to 123bn m³/yr. NPD’s forecast for the next five years shows stable high level gas sales with a small increase.

But most earlier forecasts were predicting a continuous decline in Norwegian gas production. Only two years ago the forecast was that by 2020 gas production would drop to 90bn m³/yr. Clearly this is not going to happen for at least another five years and possibly longer.

As NPD’s director-general, Bente Nyland, said: “The high production forecasts are good news for everyone who is interested in value creation in Norway.” Recent history shows Norwegian gas fields are producing more than previously assumed, thanks to efficiency measures, particularly regarding drilling of wells. Gas production in January 2018 supports this: it was 4.9% more than expected.

Cost competitiveness

In the prevailing global low gas price environment, cost competitiveness is a key factor in maintaining market share. This was the key message from the IP Week 2018 conference in February in London. This also applies to the Norwegian continental shelf, where NPD recognizes that controlling cost development is a precondition for future profitable activity and exports. Overall E&P costs have come down progressively across the Norwegian shelf since 2014 following implementation of various cost-cutting measures in the planning, execution, and operations phases. These have led to improved efficiency, simpler solutions and more use of standardised solutions.

With global gas prices expected to remain low, costs will be another issue. Most future gas fields are expected to be in remote, more hostile, offshore locations. Not only will development costs be high, but also transportation costs. However, between 2014 and now, development project costs have come down by 30%-50% (Figure 2), while recoverable resources remained virtually unchanged. With the oil price rising, this is having a positive knock-on effect on project economics.

NPD says that the greatest cost reduction was for new facilities and development wells, where more optimised solutions and simpler designs, as well as more efficient implementation, produced considerable cost reductions. This was in addition to the effects of lower supplier prices.

Operating costs have also been reduced by around 30% since 2014, partly through streamlining and lower supplier costs, although the latter are set to rise as a consequence of the higher activity level. At the same time, efforts are under way to implement new measures for additional improvements and cost reductions, with the aim to maintain the competitiveness of Norwegian gas.

Future resources

In the 50 years since Norwegian petroleum activities began, about 45% of the estimated total recoverable resources have been produced on its continental shelf. Thus, there are large remaining resources, and it is expected that the level of activity on the Norwegian shelf should continue at reasonable levels for another 50 years.

But beyond the five-year period to 2022, NPD says that without new fields and large-scale intervention to maintain production from existing fields, oil and gas production from the Norwegian shelf would continue to decline. In the longer term, the level of production will depend on new discoveries being made and the development and implementation of improved recovery projects on existing fields.

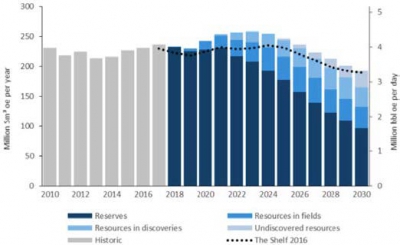

Production from undiscovered resources will likely take on greater significance in the run-up to 2030 (Figure 3). In 2017, NPD updated its estimates for Norway’s undiscovered resources. This suggested the volume of resources in the Barents Sea to be around 80% higher than in the previous analysis from 2015, while the estimates for the North Sea and Norwegian Sea remained unchanged.

Figure 3: Historical and forecast production 2010 to 2030

Source: NPD

Nyland said: “Nearly two-thirds of the undiscovered resources are located in the Barents Sea. This area will be important in maintaining high production over the longer term.”

Figure 3 shows NPD’s latest production forecast compared with the forecast presented one year ago – ‘The Shelf in 2016’. Unfortunately NPD does not show natural gas separately - only the combined oil and gas production forecast, in barrels of oil equivalent (boe). However, NPD expects that the ratio between produced gas and liquids will remain roughly equal in the next few years.

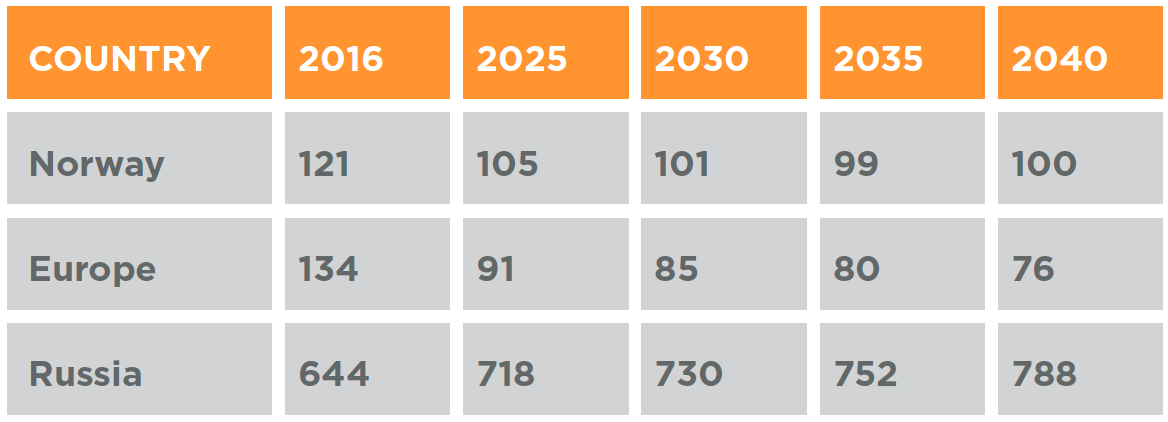

According to the International Energy Agency’s (IEA) World Energy Outlook 2017, Norway’s gas production will decline gradually after 2020, making it necessary for Europe to import Russian gas and possibly LNG from the US and elsewhere (Table 1).

Table 1: Natural gas production by Norway, Europe and Russia between 2016 and 2040, according to IEA (in bn m³)

According to IEA, the decline in combined gas production by Europe and Norway between 2016 and 2040 is expected to be 79bn m³. This could be more than covered by low-cost Russia whose gas production is expected to increase by 144bn m³ over the same period.

If Norway’s production is to be maintained at a high level beyond 2025, more resources must be discovered, requiring access to new exploration areas. NPD believes that exploration activity must be increased from today’s level, in both mature and frontier areas. Without this, the country’s production is in danger of going into permanent decline. These are the challenges that make Norway’s production level in the years to come uncertain.

In support of this, an auction in January 2018 for new offshore acreage was record-setting for Norway, with 75 licences awarded: eight in the Barents Sea, 22 in the Norwegian Sea and 45 in the North Sea. Licences were awarded to 34 companies, spread out among small and international majors such as Shell, ExxonMobil, Total and ConocoPhillips. Another licensing round is being planned to take place during the first half of 2018.

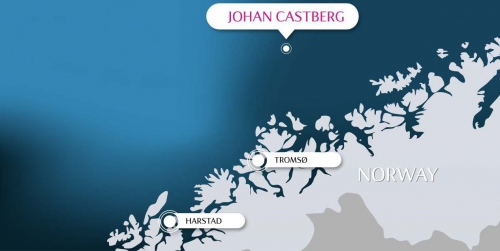

This improved interest is much needed. Norway needs to bring new fields into production. Drilling in 2017 produced disappointing results. And after Statoil’s $6bn Johan Castberg oil field starts production in the Barents Sea in 2022, there are not many new projects in the pipeline. However, based on spending budgets efforts to find new oil off Norway are expected to double in 2018, with 45 to 50 exploration wells drilled, well up from 26 in 2017. This is generating renewed optimism in Norway’s oil and gas sector.

Credit: Statoil

Clean climate impact

Norway’s energy minister, Terje Soeviknes, said Norway must identify potential offshore oil and gas reserves near its northern maritime border with Russia to better protect its economic interest in the remote Arctic region. This may hold undiscovered resources estimated at 8.6bn boe.

But this is not without its challenges. Norway has positioned itself as a leader on climate change. As a result, during the September elections, there was intense debate over the country's identity as a major oil and gas producer. The record number of new leases awarded for offshore oil and gas production in January, especially in the Barents Sea, attracted particular criticism from environmentalists.

There are calls that If Norway wants to be a “low emissions society,” it should start making the country's oil production more consistent with the Paris Agreement. Norway has pledged to reduce its own emissions to 40% below 1990 levels by 2030 and to become a 'low emission society' by 2050.

Public opposition to oil and gas drilling is increasing. For the first time, an opinion poll last year showed a majority of Norwegians favouring leaving some oil in the ground. There is growing questioning of the industry among Norwegians, who are debating the moral and financial merits of oil and gas as the world steps up the fight on climate change.

An unprecedented lawsuit was brought by environmental groups against the government over Arctic licenses, citing the Paris climate agreement and right to healthy life, but it was defeated early in January this year.

They have now launched an appeal. If such actions continue in the longer-term, they risk introducing uncertainty and may at some stage start having an impact on new investments. And with investments into the development of deepwater fields running into billions of dollars, to be recovered over the life of a field, such uncertainties may become problematic, possibly threatening the very future of the Norwegian oil and natural gas industry.

One of these groups is Natur og Ungdom (Nature and Youth). This is unexpected as this is the group benefiting most from the affluence created by oil and gas and the Norwegian Sovereign Wealth Fund (SWF).

Norway’s $1 trillion SWF, built on oil and gas income, has asked for permission to sell fossil fuel stocks, sending shock waves through global markets. It cited financial reasons and diversification of its holdings away from oil and gas as the government’s 67% stake in Statoil means that Norway already has an outsized exposure to the oil and gas industry. This includes exiting its positions in ExxonMobil, Shell, Chevron, BP, Total and other energy stocks. Norway’s finance ministry, which oversees the fund, said it will study the proposal and may take a year to decide what to do.

However, such moves add to the risk of wider divestment from fossil fuels by global institutions and funds concerned about reputational risk and exposure to fossil fuel assets.

In response to this pressure, the government plans to start working on a resource management plan for the Barents Sea, which is expected to be presented to parliament in 2020. Soeviknes said earlier in February: “We need to start the discussion about what to do in the far north.”

After all, according to NPD, oil and gas are vital to Norway’s economy, representing 12% of gross domestic product and more than a third of its exports.

What does it all mean for Europe

Norway allocates nearly all of its offshore production to the export market, and of that, nearly all is piped to Europe.

As a result, Norway’s future gas production and reserves are of crucial importance to Europe. But so also is the price. Gas from Norway will have to compete with the price of Russian gas in European gas trading hubs. As production moves further north this may become a challenge.

As Figure 3 shows, without new significant discoveries in the Barents Sea, after 2025 Europe increasingly will have to rely on gas or LNG imports from others to make up the difference. And as things stand Europe has limited options for new gas supply. The most likely source could be Russia (Figure 4).

As Figure 4 and Table 1 show, while gas production by Europe and Norway is likely to drift downwards, Russia continues to power ahead.

It is, therefore, not surprising that a rapprochement between the EU and Russia appears to be in the cards. As Jonathan Stern, chair, natural gas programme, Oxford Institute of Energy Studies, said at EGC 2018 in Vienna, “the two sides see an increasingly urgent need to get together and discuss how the relationship is going to be managed.”

Rystad Energy’s vice president for gas markets, Carlos Torres Diaz, said: “The higher exports have provided reliable supply for Europe and give an indication that the strategy followed by both Russia and Norway has been to maintain their market share, benefiting European consumers as prices in northwest Europe have remained rather stable. This has also kept new US supplies of LNG out of the region.” It appears that this strategy will continue, at least for the foreseeable future.

Charles Ellinas