[NGW Magazine] Winter tests European market resilience

Low storage levels, a lack of LNG, and low Groningen output pushed prompt UK and Dutch hub prices sharply higher in the freezing last week of February. But the changing energy balance makes it hard to draw conclusions for the future.

In the UK, the National Balancing Point day-ahead contract traded at around £1.15/therm (about $16/mn Btu) on 28 February, following earlier six-year records set the week before and in December. The additional volatility could raise the risk premium for underlying gas prices, which have risen by a third over the last two years. Longer term, on the other hand, a sharp downward revision to power generation demand forecasts – if accurate – by the UK government could cause downside volatility.

Prompt UK gas prices jumped by the biggest daily amount in 12 years February 28, with day-ahead up by 30% on the day before, and closed at their highest since March 2013, driven by exceptionally cold weather. Even as NBP surged, low end-winter European stock levels and forecasts of continental European demand 50% above normal on February 27, saw the Dutch Title Transfer Facility-NBP spread narrowing as the cold snap set in, leading to a fall in Interconnector UK (IUK) and Balgzand-Bacton Line (BBL) exports to the UK. The TTF and the NBP are Europe's most liquid and competitive hubs.

Norwegian exports to Europe however, were running close to capacity of 3.9 TWh/d late in February; and Russian exports into Germany were flat out. LNG flow, on the other hand, was subdued: so far this winter, high Asian prices have kept UK and European LNG deliveries to a minimum, but now those prices have fallen, a pick-up in arrivals is expected in March.

The high gas prices have also led many generators to switch to coal – causing a reduction in generator gas burn, partly offsetting very high heating demand; and some of the highest UK coal use figures since the government introduced its own carbon floor price of £18/metric ton in 2016, or about three times as high as the European Emissions Trading Scheme. Nevertheless, gas demand rose to a forecast 400mn m³ February 28, about 100mn m³ above seasonal norms.

There was a significant switch to coal on the continent too, where gas prices rose to €1.7/MWh above the fuel switching range. Although the UK’s Rough storage was out of action, medium range UK storage had been built up to three-quarters full going into the cold snap and was able to meet 21% of demand February 26, relieving pressure to some extent.

Longer term trend

The added volatility from this and other spells earlier in the winter and last autumn is expected to raise questions over future market direction, as traders build in a more substantial risk premium into underlying contracts. As was seen in December - when the Forties pipeline was shut-down and Russian supplies disrupted – as well as late in February, UK and northwest European gas prices do appear to be ever more vulnerable to price spikes. This is particularly the case in winter, when high northeast Asian prices keep LNG deliveries to a minimum.

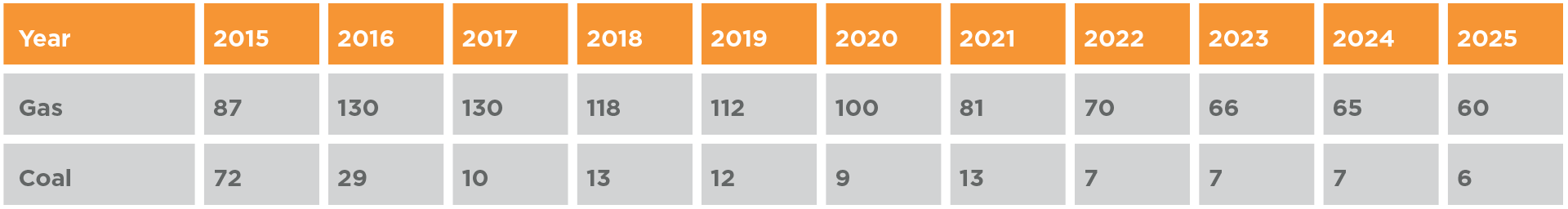

Table 1: Declining coal and gas forecast in UK power generation (TWh)

Source: Beis, statistics office

One trader said that if the cold weather persisted it might push up the underlying cost of gas: “If the run of weather to continues into April, and we get summer maintenance starting, then the rest of the curve, which has so far remained reasonably rangebound, may have a bit of a rethink.”

So far, underlying prices (for delivery in the year from October 2019) have shown little reaction to the near-term volatility, after falling back from multi-year highs of about 48 p/th in January. But over the last couple of years, they have rise by about 30%, to around 45 p/th in late February compared to 43 p/th in April 2017 and 33 p/th in April 2016.

The bulk of the rise took place in late spring 2016, with only a slight increase through 2017 – although the higher levels are now well established. The UK Office of National Statistics expects the gas price to stay in the high to mid-40s p/th until 2023.

Bullish factors

There are a number of factors behind the underlying rise. It is partly down to a risk premium in anticipation of greater price volatility as Rough storage is wound up, along with higher than expected Asian winter LNG prices, against which the UK and Europe must compete for supply at the margin.

As domestic production falls further over coming years, along with exports from the Netherlands through IUK and the BBL as Groningen is wound down further, LNG imports could become more important, depending on demand and availability of pipeline supply from Norway and elsewhere.

Gas’ rise has also been influenced by coal prices, which have surged by more than 50% since summer 2016. For example, calendar year 2019 stood at $57/metric ton in mid-2016, and has now reached $83/mt.

As coal is the main competitor to gas in providing flexible generation in Europe, prices of the two fuels influence each other strongly.

However, this is not likely to last for many more years, with the new German coalition government now planning to join the UK in phasing out coal for power generation.

Threat to demand

The latest UK Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (Beis) forecasts show a quick reduction in coal use for power generation up to 2025, and as of the latest outlook, a sharp decline in gas use too (see Table 1), which could add to downside price risk, particularly after next year. These latest projections come in the wake of two offshore wind schemes winning contracts at record-lows of £57.50/MWh last autumn, compared with anticipated wholesale power prices of £53/MWh from 2023 to 2035. As a result, Beis now expects renewables to overtake gas by 2020 to become the UK’s number one source of electricity generation, with gas providing only half as much power in 2035 as had been expected in its previous report a year earlier.

As if to compound these projections, the latest UK capacity auction (in early February) – which pays for facilities to be available to produce power – once again failed to award contracts to any new gas fired power plants. Instead, a large portion of new awards went to new interconnector power supply, which can draw on cheaper Continental output that benefits from lower carbon taxes, and so can include more coal. Renewables do not compete in the capacity auctions as their availability cannot be guaranteed.

With demand for gas from power generators now expected to fall so significantly over the next few years, it may be that there will be ample gas supply to satisfy remaining demand, and underlying prices could fall back. But the absence of an adequate storage margin could still leave prices open to winter spikes: gas demand for heating shows little sign of falling at the moment, although biogas is taking a growing share, and hydrogen could become a challenge further forward.

Continental demand may keep growing, however, building on the 5-6% growth rates of 2016-2017 as nuclear and coal power plants continue to be phased out. This could even see the UK’s premium (NBP over TTF) reversed, along with the main direction of flow on interconnectors (IUK and BBL) with Europe, especially given Groningen’s restrictions. The UK does, after all, have a lot more wind than Europe, as well as plenty of gas.

Jeremy Bowden