[NGW Magazine] BP Outlook Sees Growing Diversity of Fuels

BP Energy Outlook 2018: the austerity measures, introduced immediately in the wake of the oil price collapse of 2015, will remain in place and the quest to decarbonise power must continue to eliminate coal, if gas is to thrive.

BP Energy Outlook 2018 concentrates on the energy transition between now and 2040 and considers the key uncertainties surrounding that transition. Rising prosperity will drive an increase in global energy demand by 2040 that will be met through a diverse combination of fuels, with an ever-increasing contribution from renewables.

In introducing the Outlook, Spencer Dale, BP group chief economist, said: “We are seeing growing competition between different energy sources, driven by abundant energy supplies, and continued improvements in energy efficiency. As the world learns to do more with less, demand for energy will be met by the most diverse fuels mix we have ever seen.”

Spencer Dale, BP group chief economist, addressing IP Week 2018

It is these abundant energy supplies that keep global energy prices low now and in the longer-term and it was the recurring message from the IP Week conference where the report was launched.

BP CEO Bob Dudley said that competitive pressures within the global energy markets are intensifying: “Technological advances mean our ability to produce energy is growing ever faster – be that in unconventional oil and gas, or in renewables like wind and solar energy… Don’t be fooled by the recent firming in oil prices: the focus on efficiency, reliability and capital discipline is here to stay.”

The Outlook considers a range of scenarios and explores the energy transition in terms of fuels, sectors and regions. They reflect the fact that the oil and gas sector’s future is more predictable than ever.

Much of it is based on the ‘evolving transition’ (ET) scenario, on which the remainder of this article is based, unless stated otherwise. This assumes government policies, technologies and societal preferences evolve in a manner and speed similar to the recent past, analogous ` to the International Energy Agency’s (IEA) ‘new policies’ scenario.

Based on this, the key findings are:

- The speed of the energy transition is uncertain;

- Fast growth in developing economies drive global energy demand by about a third by 2040, with oil, gas and coal each contributing around 25%, and non-fossil fuels the remainder;

- Renewables are by far the fastest-growing fuel source, providing 14% of primary energy by 2040;

- The world continues to electrify, with almost 70% of the increase in primary energy going to the power sector, and with power demand growing fast;

- Demand for oil grows over much of the Outlook period before plateauing by the 2030s;

- Natural gas demand grows strongly and overtakes coal as the second largest source of energy;

- Oil and gas together account for over half of the world’s energy by 2040. Whatever happens, oil and gas will be needed in 2040 in at least the same quantities as today;

- Carbon emissions are slowing down but will continue to rise, albeit more slowly.

This last point signals the need for a comprehensive set of actions to achieve a decisive break from the past.

Dudley said the Outlook helps inform BP’s long-term planning but “government policies, new technologies and social preferences will alter the way in which energy is produced and consumed in the future in ways which are impossible to predict today.”

Increasing global energy demand

It is expected that the world’s population will increase by 1.7bn by 2040 and world GDP will more than double. Economic growth through increasing productivity will lift 2.5bn people from low to middle incomes, mostly in Asia and Africa, with India and China accounting for a quarter.

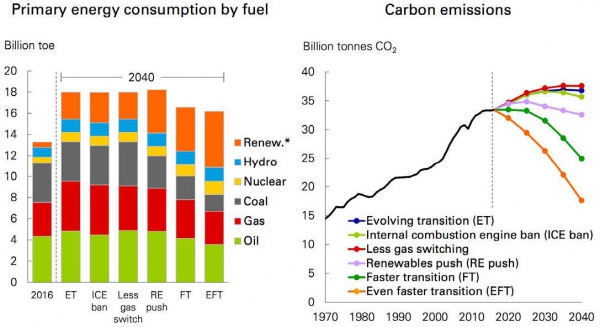

Global primary energy demand grows by 35% by 2040 (Figure 1), under most of the scenarios, little changed from last year’s Outlook.

Figure 1: Global primary energy use and carbon emissions

These scenarios focus on particular policies that affect specific fuels or technologies, such as a ban on sales of internal combustion engine (ICE) cars, more renewable energy or weaker policy support for a switch from coal to gas. Demand in OECD countries remains largely unchanged.

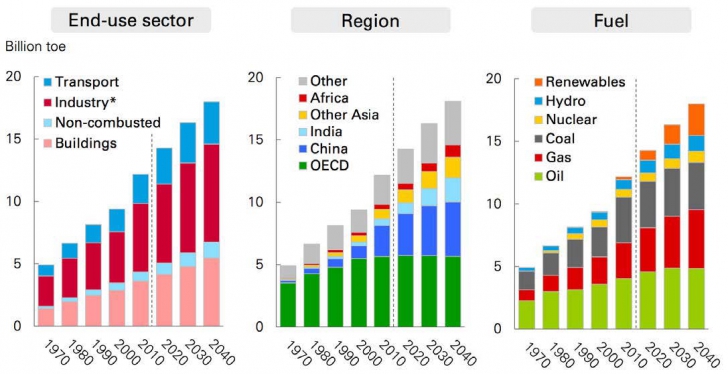

The different aspects of energy transition become clearer when looked into it terms of sectors, regions and fuels (Figure 2), based on the ET scenario.

Growth in transport demand is much slower than in the past, reflecting faster gains in vehicle efficiency.

In terms of fuels, renewable energy is the fastest-growing source, accounting for 40% of the increase but gas grows much faster than either oil or coal. By 2040, oil, gas, coal and non-fossil fuels could each account for around a quarter with oil and gas over half of that between them (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Primary energy demand transition (by sector, region and fuel)

In the ET scenario, oil demand is expected to plateau by the 2030s and will remain at the same level by 2040.

All other scenarios see oil demand peaking sooner and various rates of decline by 2040. But the dotted line shows that without further investment, and a 3% average annual drop in output, global oil needs will not be met whichever scenario is considered. As a result, the oil industry needs to carry on investing.

Impact of Renewables and carbon emissions

According to BP, renewables are by far the fastest-growing fuel source, increasing from 4% now to 14% of primary energy by 2040, Figure 2. This is driven by the increasing competitiveness of wind and solar, which are on the way to be able to compete with traditional energy sources without subsidies from mid-2020 onwards.

Figure 3: Demand for oil and other liquid fuels

_f331x338_1522184818.jpg)

In the ET scenario, renewables in power are the fastest growing energy source, growing by 7.5% per year, and accounting for over 50% of the increase in power generation by 2040.

However, in the ‘renewables push’ scenario, which assumes that government support persists around current levels until 2040, renewables account for more than 90% of the growth in power demand over the Outlook period.

This results in the share of renewables within power reaching over 40% by 2040, compared with 25% in the ET scenario. The stronger growth in renewables crowds out coal and gas to a broadly equal extent.

In the ET scenario, unless further measures are taken, carbon emissions will still be growing by 0.4%/yr, rising by a tenth by 2040. Even though this is the slowest seen over the past 25 years, it is far higher than what is allowed under the Paris agreement. So an even more decisive break from the past is needed, meaning a change of behaviour at every level.

Most studies suggest that carbon emissions would need to fall by almost 50% by 2040 to be consistent with achieving the Paris goal. In order to do this the world will need an ‘even faster transition’ (EFT). This implies a big increase in carbon prices and other policy measures.

BP also points out that carbon capture and storage is becoming critical for industry and generators.

Impact of electric vehicles

Electric vehicles (EV) are attracting considerable attention globally as a means to achieve clean air in cities, reduce emissions and contribute to improving the global climate. It is clear from the Outlook that EV adoption is accelerating much faster than BP ever imagined.

According to BP, what looks likely to be a game-changer is EV autonomous vehicles, leading to more sharing and hence less demand for oil. This Outlook shows a three-fold increase in EV’s compared with last year’s, but it still does not see them collectively as using a significant amount of fuel.

BP considers an extreme scenario, ‘ICE ban’ from 2040 onwards and that all EVs are powered by electricity from renewables. BP concludes that this is likely to reduce oil demand by about 10mn barrels/day, or about a tenth of current oil demand. And even then, the impact of this on reducing global carbon emissions is small, and less than the effects of better vehicle efficiency standards.

Meanwhile aviation and trucks will still need oil, as will sectors such as petrochemicals.

Digitalisation

At his IP Week presentation, Bob Dudley was enthusiastic about digitalisation. He said it has come into the oil and gas industry just in time. And it is producing rapid results with major improvements in operational efficiency, especially in terms of improved performance from producing wells. He was so enthusiastic that he mentioned the word ‘digitalisation’ 14 times in a 15-minute presentation that covered all subjects in the Outlook!

BP’s deputy chief executive, Lamar MacKay, confirmed that “digital transformation is underway, for example using data to intervene in issues, or to optimize maintenance programmes. We’ve seen examples where, if you get the right data in the right hands, there are up to 35% cost efficiencies in terms of revamping our processes.” He added that what “cuts across everything, is digital transformation. We’re looking at technologies which may totally transform the way we work. Things like blockchain technology, artificial intelligence and cognitive computing.”

What does it all mean for gas

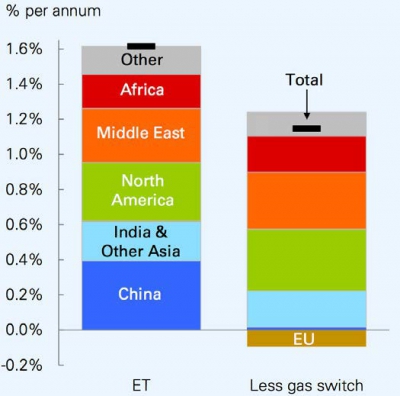

Under the ET scenario, natural gas grows strongly over the Outlook period and it is set to replace coal as the second largest source of energy. This is supported by more industrialisation and power demand in fast-growing emerging economies, as well as increasing availability of low-cost supplies in North America and the Middle East (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Gas demand growth between 2016 and 2040, with regional contributions

But coal will not go away: it plateaus and remains steady in the longer-term. China used 0.4% more in 2017 than in the year before, and by about 4% in India.

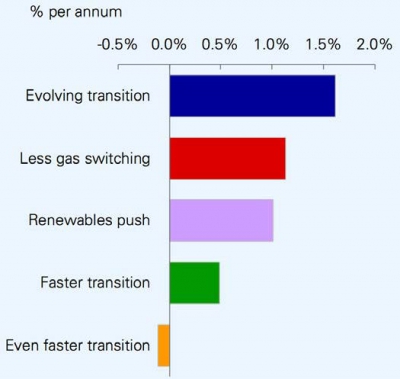

However, the Outlook shows that gas is resilient under a range of scenarios, including less coal-to-gas switching, faster renewable penetration, or a more comprehensive set of climate policies (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Possible risks to the outlook for natural gas– demand growth between 2016 and 2040 under the various scenarios

The EFT scenario, which leads to carbon emissions from energy-use broadly consistent with the Paris climate goals, sees gas demand in 2040 similar to today but this suggests that the world will require significant levels of investment in new gas production, as well as oil, in order to meet this demand.

By 2040, the US accounts for almost one quarter of global gas production. As natural gas trade continues to grow, LNG demand will increase from about 340bn m³ to about 765bn m³/yr by 2040, overtaking pipeline exports, which will rise from 486bn m³/yr to 682bn m³/year over the same period. But it is LNG trade that helps create transparent market.

Gas can have a bright future. In the ET scenario it grows about 3-times as fast as oil. This can be realised provided that it remains competitive, but it also has other challenges. It must address and drastically reduce methane emissions and must also decarbonise.

Challenges

Overall, the Outlook is quite reassuring for the oil and gas industry. But others, for example the Carbon Tracker Initiative, do not share this picture, disputing the Outlook’s findings on coal consumption and renewables penetration. Also, Bloomberg New Energy Finance (BNEF) sees faster EV penetration, predicting 530mn EVs on the road by 2040 in comparison with BP’s 300mn in its most likely scenario.

In this year’s Outlook the estimate of renewables growth by 2035 is 15% higher than in the 2017 Outlook, while oil, gas and coal demand are revised downwards. This is attracting criticism that BP is dragging its feet, not fully recognizing the rapidly increasing contribution to global primary energy from renewables. In fact, over its seven outlooks to date, BP has consistently had to revise renewables upward and gas downward, reinforcing this criticism.

Questions that the Outlook does not address include: what would happen to oil demand if heavy transport and shipping were also electrified? What happens if increased regulation globally to reduce emissions catches and spreads further?

Critics also picked on the fact that Spencer Dale argued strongly against regulation to reduce emissions during the launch of the Outlook. He based this on the argument that “It’s hard for any government to pick winners and losers.”

However, Colin McKerracher, strategic lead for transport BNEF, recognizes that “These big integrated exercises are difficult”, adding that the Outlook “is a thoughtful look at how the world will produce and consume energy over the next 20 years.”

At IP Week Bob Dudley reiterated the stiff competition posed by an abundance of energy resources, more energy efficiency, renewables and the stubbornness of coal. Productivity must increase as there is no alternative to cutting costs. Those who can produce more competitively will survive – the rest will struggle.

Charles Ellinas