[NGW Magazine] Gazprom Wards off TPA at Home

The long-standing agreement between Gazprom and the government is holding up, despite the pressure to open up the export pipelines to third-party access; Gazprom's interests are safe for now.

The question of whether to liberalise Russia’s gas system so that independent producers can access export markets has cropped up with particular frequency in the context of Nord Stream 2.

If the government allowed Rosneft and others to access the 55mn m³/yr pipeline to Germany then the problem of Gazprom’s monopoly would be solved, and the European Commission would have one less problem to overcome.

But so far the idea has been rejected as not being best for Gazprom – and hence not best for Russia either.

In the oil market, competition between traders is growing. Although a potential new trader is not likely to enter the market because of the well-established connections between the other players, anyone can theoretically take part. Transneft is the monopolist transporter but it does not produce or buy oil for trading on its own account.

This is not the case with the gas sector. Gazprom, the biggest gas producer and supplier in Russia, is also the operator of the pipeline network and it has denied other producers third party access (TPA). Even if the grounds for doing so are tenuous, the last few years have shown that there is little chance of wider reform, as it is not in line with Russian gas policy.

The unified gas supply system (UGSS) is the main component of the Russian transmission system and – with its 171,400 km of pipelines and other infrastructure – is viewed by many Russians as the eighth wonder of the world.

It is a unique engineering complex, encompassing gas production, processing, transmission, storage and distribution facilities. These ensure continuous gas supplies from the wellhead to the burner tip in the world’s largest country.

For Russians, unbundling would be a step too far. Gazprom in various forms has co-ordinated the network since 1961 as its sole owner and it dominates all the other segments of the domestic gas value chain too, and it has worked.

All legal issues concerning UGSS and the relationship between Gazprom and other gas market players have been regulated since 1999 by the federal law on gas supply (FLGS). Russia’s domestic gas transportation rules have been liberalising since mid-2000s and, bowing to regulatory and anti-monopoly acts, there is non-discriminatory access to the UGSS.

Reforms have raised the share of other parties since the late 2000s but there is no law giving access to export pipelines or to those that are not part of the UGSS.

Testing the rights

A long-standing dispute between the Sakhalin 1 owners – Russian Rosneft, US ExxonMobil, Japanese Sodeco and India’s ONGC – and Gazprom concerning the access to the Sakhalin–Khabarovsk–Vladivostok pipeline ended in December 2017. The energy minister Alexander Novak announced that gas from Sakhalin 1 would be sold by Gazprom's Sakhalin Energy consortium on condition that Gazprom supplied 2.3bn m³/yr to Rosneft's petrochemical company in the east. The pipeline, according to Gazprom’s website, is part of the UGSS, and so open to all.

In 2015 a court confirmed Rosneft's right to access the trans-Sakhalin gas pipeline but Sakhalin Energy did not allow it. Rosneft went to appeal; and in February 2017 it applied to the federal anti-monopoly service (FAS) for a ruling. A year later (March 12, 2018) the FAS closed the case as the court had proved Rosneft's right to use it and found that Gazprom had violated antimonopoly law.

Rosneft has also sought access to Power of Siberia, and in theory it has it for purely domestic gas sales; but according to experts, Rosneft wanted access in order to export gas to China. Experts argue that Power of Siberia is an international gas pipeline. According to the law on gas exports of 2006 the only owner of access to export pipelines is Gazprom.

The relationship between TPA and national energy security makes it difficult to gather comments from Russian experts. Generally, they prefer to say that non-discriminatory access to the Russian UGSS already exists. For example one said that every major gas company is a tool that exists to assist and support national policy, and that wider access to UGSS would be against Russia’s commercial interests.

Gazprom’s official position is that it provides independent companies with non-discriminatory access to UGSS and if access is blocked, it is only because of technical reasons, a typical one being that there is no spare capacity for non-Gazprom gas. However, Gazprom believes that Russia's position on TPA needs to be explained to the public. Russian newspapers such as Kommersant have said that Gazprom has ordered a number of articles to promote the Russian viewpoint in Europe, and to explain the threats resulting from export market liberalisation – especially in the gas export context.

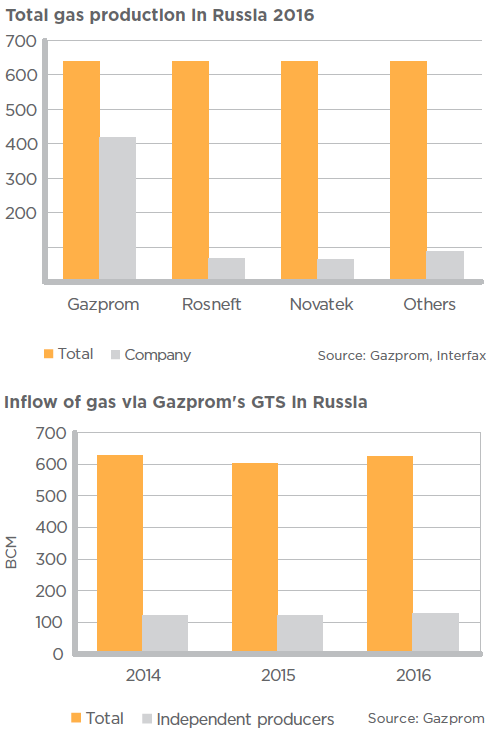

Europeans are keen for the pipes to be separated from supply and trading, as their market works on the TPA principle whereby one business cannot cross-subsidise the other, charging a lot for transport and so undercut the competition for supply. By contrast, in 2016 Gazprom’s grid pumped gas for 24 independent companies, totalling 129bn m³, just a fifth of all the gas distributed in Russia. That leaves four-fifths in Gazprom’s hands; whereas in Europe this percentage is lower in almost every case. For example, in Poland, generally held to be one of the least competitive markets, state-majority-owned PGNiG in 2017 had 73.7 % of the market. It is therefore understandable that independent companies in Russia should want a bigger share, and from their point of view the situation is not that great especially given the fact that despite long-standing laws, independent producers have only in the last decade begun to get more access to Gazprom's domestic pipelines.

For example, between 2008 and 2011, the FAS brought 28 cases against Gazprom, accusing it of hampering access to the UGSS. Perhaps for this reason from 2015 FAS has regulated the fees. However, Gazprom is trying to increase shipping fees for its competitors. In June 2017 it wanted to raise them by about 3.9% from rubles 65,1/’000m³/’00 km, but the ministry of economic development and the ministry of energy blocked the idea.

Gazprom’s argument was that transit fees have not gone up since 2015, and according to company data, the cost of pumping gas belonging to independent gas producers in 2017 was rubles 69.2/’000 m³/’00 km, which was more than the tariff. Another argument was that independent producers do not share fairly in the burden of maintaining the UGSS. Gazprom invested more than $16bn in the years 2012-17, although some of this might have been for export-related infrastructure.

There is another argument saying that a 3.6% increase in transit fees will not reduce the pre-tax profits of independent producers dramatically, while on the other hand it would bring Gazprom only $177mn-$355mn – depending on the weather and so on – and this is small beer compared with how much Gazprom has already invested in the system. According to Vygon Consulting project manager Dmitry Akishin, the optimal tariff increase should be around 10%.

According to the economic development ministry’s forecast for 2017-19, tariffs for shipping gas for independents should not rise faster than wholesale gas prices for industry. And the ministry proposed an increase of 1.9% while his counterpart in energy proposed 1.7%. The position of independent producers is clear: they want 0% tariff indexation and deputy prime minister Arkady Dvorkovich is in support of this position.

Further, at last year’s St Petersburg International Economic Forum, Novatek's CEO Leonid Mikhelson said: “Unjustified decisions to hike pipeline tariffs for independent companies can lead to a gas deficit in Russia.” He also underlined that the first prority was to set up a methodology for tariffs. He also said that the current tariff was too high, an opinion shared by many independent producers.

Tariff dispute

A representative of Rosneft said: “The indexation of the tariff for gas transportation, proposed by the FAS, is not justified. The company understands that tariffs should not be raised, but it should be calculated using a new methodology, taking into account a reasonable level of costs which is set by the regulator.”

He added also that Gazprom was investing more than necessary in the gas transportation system. In addition, it mainly invested in the export-oriented gas transportation capacities, which are hardly used by independent participants. Moreover, according to open-access government information, the capital expenditure on domestic gas pipelines is falling, which should mean lower tariffs. In 2017, the issue of tariffs has not been resolved. The head of FAS Igor Artemyev predicted this as long ago as August and said that that the decision would be taken this year.

The existing legal and regulatory frameworks of UGSS and non-UGS systems and transportation tariffs do not adequately meet today’s changes in the Russian gas market, least of all in the rapidly growing LNG sector and the role it could play in the liberalisation of the Russian domestic market and export routes.

However, the Russian LNG sector is still a work in progress and there is no regulation of small scale LNG market (SSLNG) and the niche markets in this sector. The position of the administration is crucial but first it has to compare opportunities and risks. On one hand LNG can increase the efficiency of the UGSS. But on the other, in the long term, companies may want to create alternatives to the UGSS SSLNG value chain, and so weaken the government’s position.

This is especially likely to happen if the independent producers cannot grab more of the market which will drive them naturally to SSLNG, bypassing the pipelines. This situation is a paradox because Gazprom is already the main player in SSLNG market. It might try to defend its position there in order to avoid weakening its pipeline business.

In addition, experts think the SSLNG sector is seen as a complementary part of the gas sector in Russia, used – as in China – to gasify regions far from gas pipelines; and in the transport sector. But what if companies start trying to create demand for SSLNG in gasified regions? The main obstacle is economic: in general it is not thought to be profitable for an independent operator to develop its own LNG value chain without using UGSS.

Moreover, Russia’s president, Vladimir Putin during the Yamal LNG launching ceremony in Sabetta last December, said that LNG projects and gas pipeline projects were not competitors: LNG cannot affect gas pipelines. The assessment of the situation becomes even more complicated because government programmes concerning SSLNG have just started and most independent producers are waiting to see how they are implemented. This is probably why the LNG sector will develop slowly and remain under state control. A similar question applies to gas exports. Pipeline export is dominated by Gazprom. And independent producers hope that LNG exports are not under strong government control especially in the context of ambitious plans to increase Russia’s share of the global gas market through LNG. It brings hope that liberalisation of the access to LNG export routes will become more open. Only three companies meet the criteria set by the Law on Gas Exports, allowing these companies to export LNG: Gazprom, Rosneft and Novatek.

The expansion of LNG exports will be keenly watched, since producers of SSLNG will be able to export LNG up to 400 km from the Russian border to the first refuelling points built, according to a European Union directive 2014/94/EU, along the existing TEN-T Core Network.

Regardless of the policy and security risks, the option that access to the gas system would be similar to the Italian one, where Eni has 54% market share, does not seem probable. In addition, the general director of NIIgazeconomika – Gazprom’s leading research centre which forecasts gas industry development – Nikolal Kislenko told a conference last year that in the summer months of 2017, independent gas producers produced about 2.5bn m³ more than Gazprom and added that it was not correct to describe Gazprom as a monopoly.

The most probable scenario is that Gazprom will carry more and more gas for third parties but without any detriment to itself. And SSLNG will be developed under strong governmental regulations; and no project that could jeopardise government policy will be introduced. These considerations all make it unlikely that there will be a Transneft for Russia’s gas sector.

Kamil Sobczak