[NGW Magazine] Pragmatic Approaches to the E Med

How much simpler it would be if the eastern Mediterranean's gas reserves sat instead under Belgium or some other OECD country. However, they are where they are, and some of them seem destined to remain there for even longer.

Ever since the discovery of the Tamar gas field in Israel in 2009, natural gas discoveries in that part of the world have sparked a lively debate regarding their potential to aggravate existing conflicts or facilitate co-operation and peace. Indeed, oil and gas findings and potential reserves (Figure 1) have led to some realignments between the states of the region, but also had huge economic implications.

Figure 1: Eastern Mediterranean exclusive economic zones, blocks, gas fields and LNG terminals

_f600x412_1526838977.jpg)

Credit: MEES

A conference in Nicosia in April 2018, organised by the Italian think-tank Instituto Affari Internazionale (IAI) and PRIO Cyprus Centre attempted to critically evaluate energy prospects in the region, and their potential contribution to European energy security. An effort was also made to realistically assess the peace potential of hydrocarbons in view of the rising regional challenges.

What makes exports of eastern Mediterranean gas particularly challenging and difficult, especially from Cyprus and Israel, is not just geopolitical risk, but commercial risk, owing to low global gas prices. There is political risk at the point of selling. But in the end commercial realities prevail.

Discovering the gas in the region has not, so far, been stopped because of the geopolitical risk, even though Turkey has been taking aggressive action, and will continue to do so. Notwithstanding strong European Union support, neither Cyprus nor Israel are anywhere near selling their gas to Europe. They are struggling to find buyers.

The key limiting factor is gas prices. Eastern Mediterranean gas cannot match average gas prices in European trading hubs around $6/mn Btu. By the time the gas reaches Europe, whichever way it is exported - as LNG or through pipeline – the asking price would be above this, possibly exceeding $7/mn Btu. Even cheaper US LNG at prices just above the EU market range is struggling to make significant inroads into Europe.

The global ability to produce energy is growing ever faster, both unconventional oil and gas; and renewables such as wind and solar energy. Abundant and diversified energy supplies are creating a challenging marketplace, keeping global energy prices low now and in the longer-term.

The region is also suffering from a number of unresolved exclusive economic zone (EEZ) problems and enmities involving almost all key players. The urgency to confront these issues may go up if gas exports are secured.

In Egypt a number of new gas-fields are coming into operation boosting production - not just Zohr, but also West Nile Delta, Atoll and Nooros, with more to come. These will not only satisfy domestic demand this year but by next year there will also be surplus gas for export, eventually fully utilising Egypt's two existing liquefaction plants, enabling the country to resume LNG exports and fulfill existing contractual obligations.

With renewable power generation on the rise, Egypt is undergoing a complete energy transformation.

Egypt’s petroleum minister, Tareq El-Molla, is on record stating that if surplus gas supplies keep on increasing, Egypt may consider adding a third LNG exporting terminal.

This could also accommodate gas from Cyprus, possibly Israel, and even Lebanon as, if and when it gets to this stage, thus helping fulfill Egypt’s aspiration and potential to become the regional gas hub. Indeed, recent news indicate that Israel is about to export gas to Egypt’s domestic market and that Anglo-Dutch Shell is in negotiations to buy Israeli and Cypriot gas for liquefaction in its plant in Egypt and export the LNG to Europe.

The minister confirmed that Egypt is ready to receive such gas, liquefy it and export it to the international markets. However, for a new plant the tolling fee could treble, making such exports even more challenging. With Cyprus and Israel facing commercial challenges exporting their gas and with Egypt being transformed, and its economy buoyed by the new discoveries, the foundation for stronger economic integration between states in the region may not be there. However, political co-operation, excluding Turkey so far, has never been so promising.

A state of flux

Gas discoveries and exploration activities there are ongoing and are constantly shaping and reshaping prospects for the region. Tareq Baconi, Policy Fellow, Middle East and North Africa, European Council on Foreign Relations in London said that overshadowing these developments is a range of narratives that have unfolded around this corner of the Mediterranean. For example:

- While it could be a source of energy security for Europe, its reserves are too small to truly contribute to energy diversification in Europe

- Gas reserves could exacerbate tensions and aggravate political disputes between neighbors - or they could be a catalyst for peacemaking as parties and stakeholders are forced into co-operation

- The gas fields are likely to remain stranded - or they could underpin the emergence of a gas hub.

The reality is that all of these narratives have an element of truth to them, depending on the angle through which one views the region. Looking at it through the prism of Jordan, Egypt and Israel offers one perspective, while looking at it through the prism of Turkey and Cyprus or Israel and Lebanon offers another.

Given the state of flux of the region, and the complexity underpinning present dynamics, it is perhaps more useful to consider broad principles that might be shaping developments in the region as new discoveries are made on the ground rather than put forward specific predictions about future prospects.

The first is that the politics of energy more often than not simply reflect, rather than alter, the overarching politics of states. Often gas reserves reflect whatever the background political will of the stakeholders is. In other words, they will be used as tools to achieve whatever political goals stakeholders have. If the stakeholders want peace, they will be used as catalysts for peace. If the stakeholders reject peace, they will become the vehicle through which distrust is articulated.

Developments that have been taking place on the ground pay credence to this rationale. Initially, the gas reserves were seen as a panacea, a catalyst that could allow states to put aside political differences in pursuit of a greater good. That greater good was initially seen as being dependent on co-operation, particularly pre-Zohr, when it was thought that pooling regional resources together would enhance prospects for export.

Early signs that the gas reserves might facilitate rapprochement were confirmed by the speed with which Israel and Turkey set aside their political differences. This was a time when Turkey was looking for gas supply diversification and Israel believed it could emerge as the region’s core exporter.

The gas deal signed between Israel and Jordan, followed by the one signed between Egypt and Israel, underscored the optimism for those who see these gas deals as a source of regional stability. These deals, if they do come to pass, would strengthen economic and diplomatic interdependencies between these countries.

Alliance building and greater political engagement between Greece, Cyprus, Italy and Israel, around the EastMed gas pipeline (Figure 2), also suggests that new regional hubs and alliances are in the making. In reality, however, these developments are indicative less of the peacemaking potential of gas and more of greater trade openness and integration between allies.Egypt and Jordan both have peace deals with Israel that have lasted decades, with a whole history of political, diplomatic and economic facets. Similarly, Israel has been a member of the European Union’s neighbourhood policy for years, and has enjoyed friendly relations with most European member states.

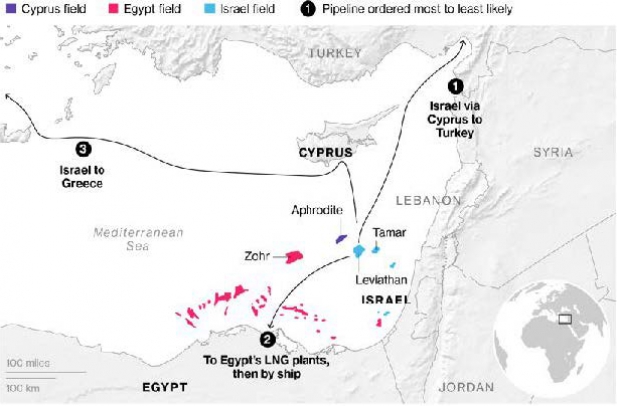

Figure 2: Eastern Mediterranean gas export options

(Credit: Bloomberg)

Turkey’s rapprochement with Israel was brief, and in any case, the political grievances that the two countries faced were more ideological than historical or territorial, and were not sufficiently entrenched to prevent closer relations.

Focusing on these elements of greater regional co-operation threatens to misrepresent the capacity of these gas reserves to create more instability. In instances where true political disputes are present, the gas finds have in fact aggravated rather than eased political tensions.

Lebanon and Israel, Cyprus and Turkey, and Israel and the Palestinians are all cases in point. Matters of sovereignty and areas of heightened political sensitivities between these parties infringe on all the developments taking place around these gas fields.

And even among parties where gas deals did come to fruition, for example between Jordan and Israel, the Hashemite monarchy paid a significant political price for its entry into this deal with the largest protests since the Arab Spring. Similar protests could also erupt in Egypt in the case of another escalation between Israel and Gaza.

In other words, the presence of gas deals do not in and of themselves mitigate the political realities that these states face in the region. Moreover, the alliances that are emerging in the eastern Mediterranean are themselves problematic in that they entrench certain power dynamics that exacerbate some of the core drivers of dispute, rocking the regional boat.

The lesson that emerges out of this, is that gas only has the capacity to act as a peacemaking catalyst in the instances where relations are already quite friendly. For broader regional stability to emerge, energy diplomacy has to be coupled with a more concerted effort to resolve longstanding matters of political dispute.

The second broad principle is that the success or failure of any project will be driven by commercial realities, not by political will. In other words, it is important to look beyond the rhetoric of politicians and reflect on the commercial viability of various initiatives.

Onlookers might be forgiven for looking at the eastern Mediterranean region over the past few years and thinking that Israel could emerge as a key reliable source of gas for Europe. The political posturing around the prospects of the EastMed gas pipeline presents this ambitious project as being closer to certainty than is really the case.

Facts on the ground present a different picture. It took just over two years for Eni to develop Zohr and for gas to begin flowing from this field into Egypt’s vast domestic market. Leviathan, which was discovered in 2010, five years before Zohr, has not yet begun producing. The reason for this is that Israel has no commercially viable way to export its gas to market, but only difficult options, while Egypt had a readily available domestic market as well as spare LNG capacity for exports further afield.

Since Zohr was discovered, the economics on the ground have pointed to the likelihood that Egypt will emerge as an energy hub in the near future. The political discourse on the other hand has continued to push forward the notion of the EastMed gas pipeline. Despite the significant commercial, political, and technical difficulties associated with this pipeline, significant amounts of resources and political capital have been expended on making it appear to be near becoming a reality.

These two projects might not be mutually exclusive, and there might still be a case for examining the commerciality of the EastMed gas pipeline. However, to get a true reflection of the reality on the ground, one must follow the money. And the money now points to Egypt emerging as an energy hub. Cyprus and Israel are now both seeking to export gas to Egypt, either for use in its domestic market or for re-export through the LNG terminals.

This is a more important and pragmatic export option to concentrate on than the likelihood of the EastMed gas pipeline becoming reality. For policymakers, it raises several areas of importance that would get marginalised if focus shifts primarily on the EastMed gas pipeline. For example, what are the challenges and opportunities offered by Egypt as a hub? Is there sufficient capacity? How does one deal with Egypt’s troubling political reality?

Another example for the ‘politics versus economics’ debate is the long-standing conversation within Europe itself. While the EU has consistently called for diversification of gas supply from Russia, is such an aspiration realistic, or even necessary given the internal shifts taking place within Europe regarding energy security and gas consumption? How can the diverging interests of various member states be better represented in EU decision-making? And how does this internal European conversation impact the prospects for the eastern Mediterranean? Realities on the ground demonstrate that commercial factors and access to plentiful and cheaper gas are what really matter.

Regional energy security

A senior programme officer for energy security at the OSCE, Daniel Kroos, described how the organisation could contribute to regional security, including environmental and human security. OSCE provides advice on protection of critical infrastructure with the aim of ensuring connectivity, sustainability, governance and resilience. Climate change, terrorism and cyber attacks are issues being addressed.

The current situation in the eastern Mediterranean reminds him of problems in the Caspian Sea in the 1990s. Energy security concerns, and security of critical infrastructure such as pipelines, have become more prominent on the public and political agenda. Natural gas trade via pipeline can be most closely linked to conflict due to the fixed nature of infrastructure, spanning multiple jurisdictions and geographic spaces.

Increased energy demand will lead to a 40%-50% increase in energy demand in the region as a whole, driven by high growth prospects and a very young population. The importance of natural gas will rise in the power generation sector but renewables are playing an ever larger role, with renewable capacity of 16 GW/yr expected to be added over the next 20+ years. Nuclear energy is also becoming important, with new projects in Turkey and Egypt.

The issue of regional energy demand was taken up by Nicolo Sartori, head of energy and climate at the IAI.

He said that gas development will involve a mix of global sales, which are price driven, and sales to regional and local markets, subject to investment risks. However, given the challenging global market climate, his recommendation is to develop regional and local markets first. He suggested that in Cyprus gas should be made available to both the Greek and Turkish Cypriot parts.

With the Southern Gas Corridor and TurkStream gas pipelines, and other gas projects under consideration, Turkey is important to EU’s energy security and has the potential to become a market for this gas too. As a result, EU diplomacy in the region requires engagement with Turkey. Isolation of the country can be counter-productive. It needs to be kept in the loop.

He reflected that using the gas regionally can bring communities and countries together. Egypt could encourage a more co-operative approach in the region through its potential hub role.

Need for dialogue

Kroos commented on the need for more regional dialogue. The current energy landscape and future projections in the region offer plenty of opportunities for greater regional co-operation on energy issues.

A deputy director at the Atlantic Council’s global energy centre Ellen Scholl took this up and talked about the need for inclusive regional dialogue and the potential contribution of East Med gas to EU energy security. But this faces the challenges of a competitive market and uncertain EU gas demand in the future. Other challenges include:

- Renewables

- New discoveries

- Unconventional resources

- Pipeline politics

- Security of critical infrastructure against attacks

- Resource ownership challenges

Gas there is expensive to produce and develop and faces commercial challenges. US LNG is struggling to get inroads into Europe thanks to low gas prices.

Regional agreements between Israel, Jordan and Egypt provide a promising basis for co-operation. The development of the resources also offers the potential for increased regional co-operation and energy security, and, more realistically, for countries of the region to meet their own energy needs, which also has positive implications for stability.

However, experience shows that when the political basis, or space for co-operation, is already in place, things go more smoothly for energy co-operation. Geopolitical framework conditions set the stage or make possible energy co-operation, rather than the other way around.

The current US government does not have a co-ordinated set of policies for the region as it does not see it as a top priority. On the other hand, the EU should provide a more concerted approach, combining energy with political diplomacy.

The OSCE role should also be elevated, as a trusted broker with historical experience in confidence building measures, facilitating incremental progress. It could provide a platform to discuss energy security in the hope of addressing underlying political issues.

Charles Ellinas