NOCs – business as usual [NGW Magazine]

The direction of travel of national oil companies (NOCs) is embodied in Opec’s annual World Energy Outlook 2020 report. It finds that, despite the downturn caused by Covid-19 in 2020:

- Global primary energy demand continues growing in the medium and long term: it is a significant 25% higher by 2045;

- All forms of energy will be needed to support the post-pandemic recovery and to address future energy needs; but

- Oil retains the largest share of the energy mix throughout the outlook period, accounting for a 27% share in 2045 and;

- Natural gas will be the fastest-growing fossil fuel between 2019 and 2045 and, after oil, will remain the second-largest contributor to the energy mix in 2045 at 25%.

The report concludes that if the pandemic is contained this year, oil demand will regain lost ground and see healthy growth over the medium-term. As a result it goes from nearly 100mn b/d in 2019 to around 109mn b/d in 2045.

Most of the biggest NOCs appear to be basing their future plans on similar growth assumptions.

Rosneft’s CEO Igor Sechin warned its partners the UK major BP and Anglo-Dutch Shell last September that they were creating an ‘existential crisis’ for the oil market with their strategy of decarbonising. But he went on to say that NOCs such as Rosneft would benefit from this, by stepping in and filling the gap that they created by departing.

With future growth in global energy demand coming entirely from emerging economies, underpinned by increasing prosperity and improving access to energy, he may be proved right.

On the back of strong economic recovery, China’s Q4 2020 crude oil and oil product demand was expected to increase by more than 9% year-on-year. By the same measure, India’s Q4 2020 crude oil imports are expected to be 2% higher. The International Energy Agency (IEA) expects global crude oil demand to increase to 97.5mn b/d in 2021 – with most of the recovery during the second half – having fallen to an average of 91.8mn b/d in 2020. It is then expected to return to 2019 levels by 2023. The US Energy Information Administration (EIA) expects this to happen much earlier and probably by the end of 2021.

Wood MacKenzie also expects oil demand to recover quickly, returning close to its pre-pandemic path (Figure 1) at least for this decade.

It concludes that predictions that 2019 would turn out to be the peak for world oil demand seem unlikely to be fulfilled.

This is supported by S&P Global Platts Analytics that sees global oil demand peaking in 2040 at around 120mn b/d before declining to 116.5mn b/d in 2050 under a ‘most likely’ scenario – which is even more bullish than Opec’s own forecast.

As a result NOCs are mostly carrying on, more or less, ‘business-as usual’. Future growth in oil demand may not yet be over.

Rosneft’s bold move

Rosneft is demonstrating its faith in the future of oil by committing $134bn to a massive new oil project in the Arctic. Sechin announced last November the start of the Vostok Oil project, estimated to hold 44bn barrels and expected to produce 2mn b/d.

The sheer scale of the task becomes clear when considering that it will require 15 new towns to house the 400,000 workers that will construct and operate the project. It will also require a fleet of ice-capable tankers to transport the oil to markets.

Oil trader Trafigura has acquired a 10% stake in the project and with future markets for this oil likely to be in Asia, Rosneft hopes to attract Chinese and Indian investors too.

Rosneft also has plans to expand this even further. It is in the process of acquiring the Payakhskoye oilfield that is estimated to have reserves exceeding 7.3bn barrels. Clearly, Rosneft is going to keep pumping.

_f400x464_1611047303.JPG)

Rosneft sees longevity in global oil demand growth. In fact Rosneft’s plans undermine BP’s green pledges and its commitment to reduce reliance on fossil fuels as early as 2030. BP owns 20% of Rosneft but it has said that the company is exempt from these pledges, giving the company a hedge if oil demand keeps going as strong as Rosneft expects.

UAE is going in the same direction

The UAE has also been making aggressive commitments, putting its money into the future of oil and gas. Following the announcement of the discovery of 22bn barrels of unconventional oil resources and 2bn barrels of conventional oil in November, Abu Dhabi’s supreme petroleum council approved $122bn capital expenditure over 2021-25. This was a part of a plan to increase oil production capacity from 4bn to 5bn b/d by 2030.

Investment did not stop in 2020. In September, the Abu Dhabi National Oil Company (Adnoc) entered into a $20.7bn deal with a consortium of six global investors to form a new company, Adnoc Gas Pipeline Assets, with lease rights to 38 gas pipelines.

Just over a year ago Adnoc CEO Sultan Al Jaber said that about $11 trillion in new investments will be needed for the oil and gas industry to keep up with projected global energy demand. He said: “In the short term, global economic uncertainties are creating market volatility and impacting the energy demand. But, in the long term the outlook is very positive and in fact robust.”

A year of turmoil and crisis, with many predicting the demise of the oil and gas industry, has clearly not deterred Abu Dhabi.

The UAE is banking on the future of oil and gas in terms of exports, it is hedging its bets domestically. “By tapping into gas caps, undeveloped reservoirs and unconventional resources, we are unlocking vast reserves of natural gas,” Al Jaber said. But he stressed the need for renewables as well as nuclear power too.

In addition, last month UAE’s crown prince mandated Adnoc to explore opportunities in developing hydrogen as a fuel source.

In terms of environmental impact he said UAE’s oil and gas production was among the least carbon-intensive in the world. UAE leads the industry with the lowest methane intensity and was one of the first to invest in carbon capture and use – capturing carbon dioxide from industrial facilities and injecting it into oilfields to enhance production.

Saudi Arabia leads Opec action

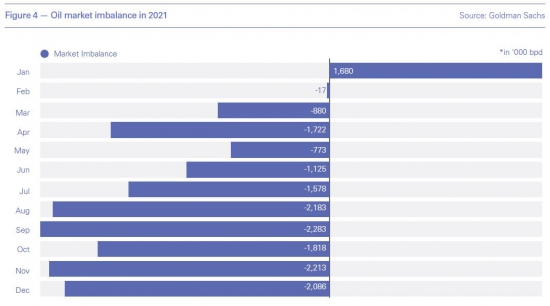

Saudi Arabia’s commitment to oil price stability took centre stage January 5 when it decided to cut oil production unilaterally by 1mn b/d, in February and March. Energy minister Abdulaziz bin Salman said the aim was to support the Saudi economy and “the economies of our friends and colleagues, the Opec+ countries, for the betterment of the industry.” This did not only bolster the oil price, with Brent rising to $56/b (Figure 3), but it is also expected to bring the oil market into deficit for most of 2021 (Figure 4), helping reduce surplus stock.

Through this move, Saudi Arabia re-established its influence and leadership role within Opec and on global oil markets. As bin Salman said, it sees itself as guardian of the industry. He added: “We have the responsibility of looking after the market, and we will take all necessary actions. I have said this repeatedly and even advised that no one should bet against our resolve.”

The country ended up 2020 with a near-$80bn deficit, forcing it to cut its 2021 budget by 7%. Prices will be key: analysts estimate that the budget is based on $48-50/b.

These challenges have not slowed Saudi Aramco down. Late last month it announced the discovery of four oil and gas fields. In November it also announced a new contracting strategy for its brownfield oil and gas and plant upgrade projects, awarding eight long-term engineering contracts. Aramco plans to increase its sustainable capacity from 12mn b/d to 13mn b/d.

It is still reviewing its 2021 budget. But CEO Amin Nasser believes “the worst is behind us at this moment… We can expect a better recovery in the oil market in the second half of 2021.” He added that Aramco continues to bet on expanding in the downstream to take advantage of expected growth in petrochemicals.

Nasser said that while short-term adjustments may be necessary should lower crude oil prices continue, “we remain firm on our long-term forecasts on creating value through growth and investment.” He added “We continue to evaluate and pursue a number of opportunities here in the Kingdom, and around the world in countries like China and India.” He expects about half of the oil demand over the coming decade to come from petrochemicals, driven by Asia.

Saudi Aramco is also investing in a ‘cleaner energy’ portfolio, including blue hydrogen and blue ammonia and researching ways to reduce emissions through technology. But Nasser also believes that the global energy transition will be gradual. “Covid-19 has prompted a lot of debate and discussion that the sun has set on the oil and gas industry – that oil demand has peaked or that this is close to happening. But in my view, the reality is that conventional and new energy sources will run in parallel for many decades to come.” He added, “I do see a bright future ahead for the petroleum industry.”

China’s priority: security

Security of energy supplies tops China’s energy concerns and priorities as it enters 2021. As its spat with the US escalates, with no end in sight, so does its fear that dependence on energy imports has security implications. Even though president-elect Joe Biden may bring some respite, the fundamental issues are expected to remain.

As a result, China plans to increase oil and gas exploration further and accelerate the construction of more oil and gas storage and pipeline infrastructure.

Over the past decade domestic oil and gas production has not been keeping up with growth in demand. As a result, China’s import dependency increased, particularly with regards to oil where imports now make up over 73% of total demand.

China’s proposed 14th Five-Year-Plan (FYP), covering the period 2021 to 2025, aims to redress that with focus on energy security and environmental sustainability. In addition, the emphasis will be on boosting domestic demand to drive economic growth.

The 14th FYP is also expected to set up the basis of energy transition plans to deliver China’s target to achieve carbon neutrality by 2060 – a deadline that some view with scepticism.

The beneficiaries of these plans will be low-carbon fuels and petrochemicals, boosting demand for natural gas and oil. This may push peak oil demand in China to 2040.

These developments are reflected in the investment strategies of China’s NOCs, CNPC, Sinopec and Cnooc and their plans to step up domestic oil and gas exploration and production.

As part of plans to improve energy security, China is also taking measures to open up its energy sector and particularly oil, gas and coal exploration and production, to foreign investment. Adnoc and Cnooc signed an agreement in 2019 to share expertise in upstream and downstream oil and LNG. Russian and Chinese oil and gas companies are also pursuing closer co-operation.

Are the NOCs right?

The answer is probably yes. Most reputable outlooks and forecasts predict that oil and gas will still be providing a major share of global energy demand over the next 20-30 years, especially in Asia. As BP says, population growth and increasing standards of living in Asia mean that energy demand will keep rising for at least 20 years.

Saudi Aramco banks on this leading to a massive demand growth for petrochemicals, hence its $69bn acquisition of Sabic – multinational chemical manufacturing company – at the height of the pandemic in June.

NOCs such as Saudi Aramco, Adnoc, Petrobras and Pemex have been expanding their export-orientated refining capacities and their commercial and trading operations, taking on roles previously mostly confined to IOCs. In effect, as IOCs transform themselves into greener energy companies, the NOCs are stepping in to take their roles, evolving from national champions into global companies.

Expanding into petrochemicals and oil refining is also a way to mitigate against a future slowdown in oil demand growth. As Saudi’s crown prince Mohammed bin Salman said: "To completely wean a giant economy like Saudi off oil, it will require at least 50 years more. So as long as oil is with us, make more money out of it if you can."

But there is uncertainty about the future of oil demand. This is reflected in the huge range of forecasts by reputable organisations, ranging from continuously growing demand to demand declining to 30mn bls/d by 2050. The IEA is clear that in the absence of a larger shift in policies, it is still too early to foresee a rapid decline in oil demand. Depending on what happens in Asia, demand for oil and gas is expected to remain strong for some time.

And if that is the case, in order to avoid a supply crunch, upstream investments in oil and gas, and new discoveries, will need to continue. That is the premise followed by the NOCs.

So far most NOCs see no sense in joining the rush for renewables, even though some have taken first steps into investing in low-carbon energy. But none have made pledges to disclose information on their emissions or set goals for cutting emissions. These do not appear to be high priorities.

What remains to be seen, though, is what impact on demand that the new US president will have. Joe Biden committed to fully integrate climate change into US foreign and national security policies and there is a growing expectation that the US will return to its global climate leadership role. On the other hand political and economic realities may actually limit how far he moves.

He will re-engage with Europe, re-enter the Paris Agreement and mend the trans-Atlantic relationship by re-stating support for Nato. With Europe’s support he will then confront the economic and geopolitical challenges posed by China.

Biden has already indicated that he intends to work with the EU to bring the US back into the international Iran nuclear agreement. This would lead to removal of US sanctions, which would enable Iran to reinstate its crude oil exports to pre-sanction levels, over 2mn b/d, from less than 0.5mn b/d now – but this is unlikely until 2022 at the earliest.

Whenever it happens, if Opec+ is unable or unwilling to respond with further production cuts, this would risk oversupply and low prices, delaying recovery.

The oil industry is still under pressure but the new Covid-19 vaccine brings hope. Management of oversupply, as Opec+ is doing at present, will also be critical.

But in the end it all hangs on how strong oil demand recovery will this year and next – and of course oil prices.

_f600x343_1611047240.JPG)

_f550x338_1611047334.JPG)