Oil, gas and the energy transition [NGW Magazine]

Two European majors – BP and subsequently Shell – stole the headlines in August and September with their announced commitments to implement major shifts to clean energy.

This will be achieved by restructuring their businesses and reducing their investments in oil and gas and they are not alone in this.

A headline early October was: “Shell slims down to shape up for the energy transition,” with 11% job cuts as part of efforts to shift to a lower-carbon future. But it is more likely that what is driving this is Shell, which this year famously cut its dividend, placing priority on financial resilience, in response to the downturn.

This follows BP’s confirmation that it will reduce its oil and gas production by 40% by 2030 and increase its investment in renewables. BP is also in the process of restructuring, having announced a 10,000 staff cut in June.

BP’s share price dropped to a 25-year low after its mid-September presentation and by early October it was trading at 214p, down by a fifth on its price before the presentation. It appears that not everybody is convinced about the new strategy, at least for now. There is still uncertainty about how BP will deliver these plans – detail is lacking.

The story with Shell is similar. Since announcing restructuring and cuts in spending in order to increase investment in renewables and cleaner energy, its share price plummeted to 885p in early October, a 25-year low. At the start of the year it was 2300p.

Shell said in April that it is in the process of “balancing short-term needs with long-term goals” to become a net-zero emissions business by 2050.

Total is going in the same direction. It announced late September that it would increase investments in renewables and electricity to $3bn/yr by 2030 from about $2bn/yr now. It is aiming to become one of the top five renewable power producers in the world, with renewables and electricity providing 15% of its revenues by 2030.

But it also said that over the coming years growth would come from its gas business, which is expected to provide half its revenues by 2030. On the other hand, Total now expects sales of oil products to shrink by 30% over the next 10 years, representing about a third of its revenues. According to its CEO, Patrick Pouyanne, Total’s aim is to “diversify activities... increase resilience and offset oil price volatility.”

Unless there is a change, as European majors commit further to clean energy, the divide between them and the rest of the oil industry will widen. If the rest of the world does not follow Europe’s pace of change, the European majors may face a dilemma. How can they stick to their new pledges in Europe while maintaining the remainder of their global oil and gas business?

Even those who lead this transition are questioning the wisdom of committing to a large-scale shift prematurely. For example, Shell executives have “questioned whether committing ever larger sums to lower-margin businesses is a responsible use of funds.” On the other hand they also “wonder if they can justify pouring more cash into legacy businesses, with opposition to fossil fuels only rising.”

At least in Europe, pressure from investors and activists to align with Paris Agreement goals is relentless. They are increasingly calling on oil companies to become more accountable for their role in climate change, reduce their oil and gas operations and shift their business to greener investments. Persistently low returns are also having their effect, with financial institutions becoming reluctant to invest in new oil and gas projects.

Ultimately, the – seemingly dramatic – change in direction taken by European majors may be driven largely by the continuous retreat of global capital from oil and gas. The market values Shell and BP about 40% lower than it did a year ago.

For others it does not seem to be such a big problem. The US majors ExxonMobil and Chevron, the non-European international oil companies, independents and all the national oil companies are sticking with their plans, albeit with carbon reduction goals, self-imposed in some cases.

Interestingly, the share prices of US majors have fared better, with Chevron trading at about 60% of its value a year ago and ExxonMobil close to 50%.

Demonstrating its faith to the future of oil and gas, ExxonMobil has just sanctioned its Payara project offshore Guyana, to the tune of $9bn, expected to produce up to 220,000 barrels/day by 2024.

Rosneft has warned BP and Shell that the shift towards renewables could lead to supply shortages and higher crude prices, “creating an ‘existential crisis’ for oil supplies.” If majors cut investments, supply shortages would be inevitable, should demand return to pre-pandemic levels, national oil companies (NOCs) would then take a greater share of the market to compensate.

The crux of the matter is timing of peak oil and gas demand. If it does turn out to be well into the next decade, then NOCs stand to benefit as European majors reduce oil and gas production.

In addition, as the Financial Times points out, “fossil fuels’ share of the global economy dropped by just one percentage point between 2010 and 2019, despite plummeting clean-energy costs, rapid advances in battery technology and 25 years of high-level UN climate conferences. Four-fifths of the energy consumed last year still came from oil, natural gas and coal, according to the International Energy Association (IEA).”

Ultimately though, the energy transition is a reality and, at least in Europe, it has emerged out of Covid-19 intact. The oil and gas industry is struggling to find its footing, with some companies responding better than others. But most oil and gas companies have been preparing for a prolonged downturn.

Oil and gas in crisis

The oil and gas sector is in a state of crisis – more the oil sector than gas – and this will continue until demand and prices recover. And even then, there is great uncertainty that oil demand will ever return to pre-Covid-19 levels. This is demonstrated in Figure 1 based on BP’s Energy Outlook 2020.

The range of possibilities covered by the scenarios is huge. Similar, wide-ranging, forecasts have been produced by the IEA, the US Energy Information Administration (EIA) and Opec, with some predicting peak oil into the 2030s or beyond.

With Asia, where most growth in energy demand is taking place, turning inwards by promoting self-sufficiency for economic and security of supply reasons, the likelihood of BP’s Rapid transition and Net Zero scenarios materialising will be small. That would imply that global oil and gas demand will remain high well into the future.

It is also possible that if low oil prices persist over the next few years, global peak oil demand will slide further into the future. A significant part of the industry still believes oil demand will return to expansion once Covid-19 is under control, storing up problems if investments in new supplies remain depressed.

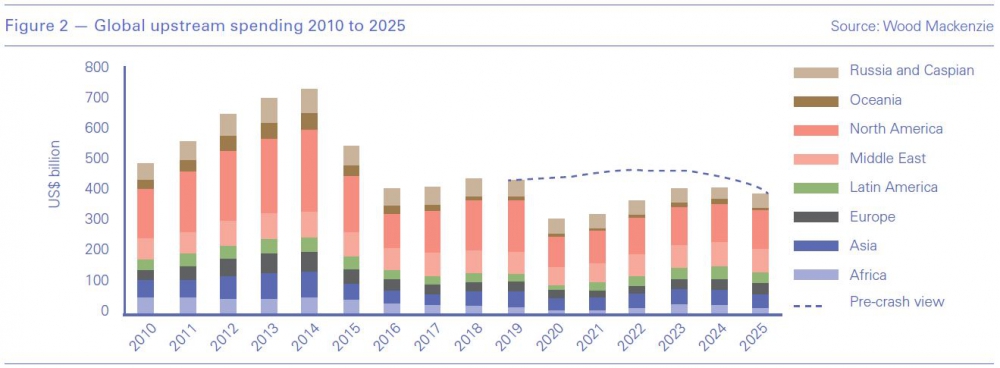

Should that happen, the massive drop in global upstream spending between now and 2023 (Figure 2) may prove problematic in terms of keeping up with the expected upturn in oil and gas demand, with a price shock in the offing.

New discoveries will be needed to replace depletion of existing fields and that will require maintaining upstream investment. The IEA has been warning that shortfalls in investment may create future supply bottlenecks.

Natural gas is being squeezed, facing competition from other fuels, including coal in Asia. The key challenge is how to make gas more acceptable as a means of achieving climate goals without eroding its competitiveness. It also faces increasing disruption from new technologies and decarbonisation policies, for example in the EU. Low price is key to its future.

But as BP points out in its Energy Outlook 2020, natural gas is more resilient than either coal or oil, owing to its broad-based demand and the increasing availability of global supplies. As such it will still be making a major contribution to global energy demand even by 2050. Oil and gas companies are counting on this, having invested heavily in LNG infrastructure.

The crisis, and the resulting restructuring of oil and gas companies, is forcing major staff cuts. Some are for strategic purposes, such as ExxonMobil’s severance of 1.600 jobs in Europe. Others are existential: forced to transform themselves into more efficient operations with lower carbon emissions, the companies will no longer need many of the traditional jobs. Equinor for example announced early October major savings from a digital approach to maintenance and subsurface head production management at its giant Johan Sverdrup oilfield. Better reservoir knowledge and well management brought savings of $220mn in the first year of operation.

The part of the industry hit hardest by the oil crisis is US shale. Headlines such as “Wall Street calls time on the shale revolution” are indicative of the extent of the challenge. But is this a lasting effect, or with prices expected to rise in 2021 will shale return, as happened before?

Certainly through many bankruptcies and acquisitions the shale industry is undergoing a massive correction. But that could make what survives healthier and more resilient – just as companies that dealt with the 2014 downturn retained their new, cheese-paring habits when prices recovered. “Never waste a good crisis,” was the watchword at upstream conferences in 2015. Standardisation of equipment, off-the-shelf instead of bespoke solutions – those were the new norms.

Funding the transition

Achieving the UN target of limiting global temperature increases to no more than 1.5 °C requires an economic transformation at a level the world has never seen before. Experts are divided on how to get there, but even the optimists concede it will require a major global shift.

Goldman Sachs estimates that investment in decarbonising the energy industry – renewables, carbon capture, hydrogen and the upgrading of power infrastructure – will reach $16 trillion over the next 10 years. Even though analysts say vast new spending is under way as the world’s energy system begins this transformation, it has a long way to go before it reaches the required funding levels, and clearly it is not uniform – more in Europe, less elsewhere. Europe cannot do it alone. It is recognised that “the task ahead is monumental.”

In developed economies, financial institutions, pension funds and investors are limiting their exposure to fossil fuel projects, with more emphasis placed on sustainable finance. But this does not extend to the rest of the world, especially to the Middle East, Africa and Asia where most of the investments in energy are taking place.

Building clean energy businesses will take time and require huge advances in clean energy technology. Unlike the traditional upstream oil and gas business, it offers low margins that may not generate the returns required to fund the build-up of the business.

That will depend on cash generated by traditional oil and gas business over a long-time. But will activists give the oil companies that time? Unlikely, at least in Europe. Pressure will continue to rise and the oil and gas companies will have to walk a tightrope during transition between providing the energy the world needs and a world becoming increasingly aware of the need for a low-emissions future. Clearly the focus will have to be on minimising the operating costs per barrel and presence in as many links of the value chain as practicable.

But European majors are going a step further. They are cutting dividends and are shifting capital expenditure allocation to renewable projects. This may amount to as much as $3bn/yr apiece during the decade to 2030. They are turning themselves into integrated energy companies, as BP put it. This is inherently a less attractive proposition than oil, gas and refining – at least until the first fruits of these efforts become visible.

Challenges

At Eurogas’ annual conference on October 1, the European Union’s commissioner for energy Kadri Simson said: “We need to supply natural gas to consumers in the years of transition.” Much was also said about the importance of green hydrogen. It was also stated that that it is essential to safeguard security of supplies and affordability during transition and that European industries and companies need to be part of the solution. But yet again, no details were forthcoming about how these can be achieved, over what time and at what cost – or how to get there.

And this is the crux of the matter: vague policies hamper investment. After Europe was flooded with cheap renewable energy, thanks to unpredicted subsidies, would-be investors in gas-fired power have had second thoughts.

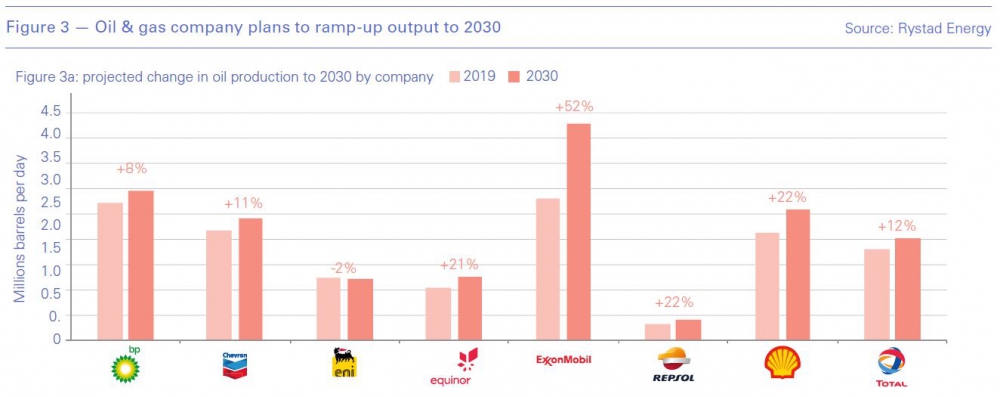

If taking climate change seriously is interpreted to mean reducing oil and gas production, that does not appear to be the case for most oil and gas majors. Based on assets companies hold and are planning to sanction, almost all look set to increase output (Figure 3). This does not take into account plans for oil production cuts announced recently by BP and Total – as neither company has yet detailed how this will be achieved. ExxonMobil is planning the biggest increase in oil production relative to 2019: by 2030 it is looking at 52% more; and for gas, 27%, by 2030.

Figure 3 does not include NOCs who are similarly planning to produce more oil by 2030; as do members of Opec. In fact Opec expects demand for its crude oil to rebound sharply in 2021, and go above pre-Covid-19 levels – close to 30mn b/d.

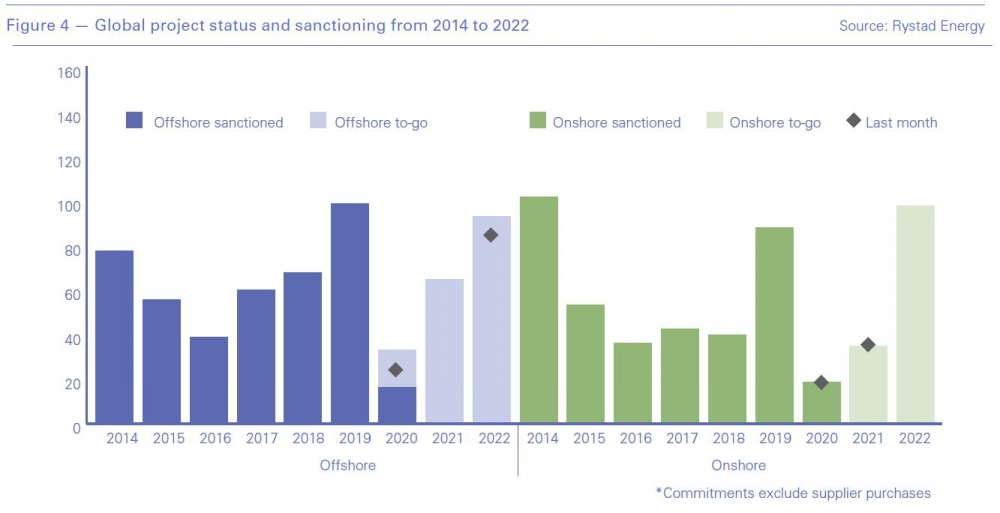

This appears to be supported by proposed project sanctioning. According to Rystad Energy, postponed plans will cause the total worth of final investment decisions to double next year and to exceed pre-Covid-19 pandemic proportions from 2022 (Figure 4). This bodes well for oil and gas production recovery.

However, IEA CEO Fatih Birol cautioned that oil-dependent countries must concentrate on diversifying their economies as the risk of a peak in demand is very real. He said: “It has never been so urgent as it is today…There will be no oil or gas country that is not affected by the clean energy transition.” On the other hand, the question still is when this peak will occur?

But the challenge for the oil and gas companies is real. By early October, NextEra Energy, a Florida-based utility and power producer, had a market capitalisation of $138.6bn, while ExxonMobil, once the world’s biggest public company, was down to $137.9bn, a fraction of its peak of more than $500bn in 2007. Its downfall is epitomised by its recent removal from the Dow Jones Industrial Average after 92 years.

ExxonMobil’s problems do not stop there. According to Wall Street the company may be facing a shortfall of about $48bn through 2021, a situation that will require it to make deep cuts to its staff and projects. And that’s after borrowing $23bn this year. However, ExxonMobil confirmed that despite planning cost cuts, it remains committed to its core competencies and “capital allocation priorities – investing in industry advantaged projects, paying a reliable and growing dividend, and maintaining a strong balance sheet.” Evidently, it is confident that oil and gas will still continue strong well into the future. It appears that, apart from European majors, most of the other oil and gas companies – IOCs and NOCs – share the same view.

An important factor is that environmental, social and governance (ESG) issues are gaining traction in Europe, and to a certain extent in the US, affecting fossil fuel projects, including natural gas. Moody’s went as far as to warn that “although natural gas transportation and distribution companies continue to provide generally safe, reliable service while reducing emissions, there are ESG reputational risks associated with any hydrocarbon-based business, including financial governance policy risks around a higher cost of capital and lower asset returns over a multi-decade time horizon,” with new gas pipeline projects facing strong challenges in the US and likely elsewhere. Moody’s also warned that “corporate sustainability strategies focused on net-zero carbon emissions goals could affect decisions about gas transmission and distribution operations.”

Within the EU potential challenges will come from the push to cut carbon emissions by 55% by 2030, while over the same period establish green hydrogen as feedstock to displace grey hydrogen. The likelihood of these goals being achieved can be boosted by increasing carbon price, with some estimating as much as €79-€102/metric ton by 2030. But such high prices could also hasten the demise of fossil fuels, including natural gas, in Europe.

Globally, even though China has committed to net-zero by 2060, it is still investing in all fuels, including clean coal – projects that will continue operating for the next 20 to 30 years. China has not yet clarified what it means by ‘carbon-neutrality’ and has not committed to a timetable how to get there. It also appears that reforestation and nature-based solutions could form a significant part of its plans. Nevertheless, this is putting huge pressure on the US to follow suit.

However, there is still the prospect of a Joe Biden victory in the US presidential elections in November, which could see the US joining the global energy transition. He has pledged to “rejoin the Paris climate deal, spend $2 trillion on clean energy, decarbonise American electricity and electrify swathes of the country’s transport sector.” But as Daniel Yergin – the oil market expert who wrote the best-selling history of the US oil industry, The Prize – pointed out, Biden is a realist. “I don’t think Biden is going to want to be the president who presides over the most rapid increase in US oil imports in history,” he said. Only Saudi Arabia and Russia would benefit if Biden oversaw a period of falling US oil production and exports.

So the energy transition will not be plain sailing globally. Unless the rest of the world follows suit in some way, Europe may simply become quite uncompetitive in global markets. There could also be social implications, including unrest, if, as a result, energy becomes too expensive. There is a long way to go yet, but the uncertainties these policies create may still usher in a chaotic transition – fast in parts of Europe but slow everywhere else. But one fact is clear: the world is hungry for more energy, and it will need all forms of energy for many years to come. Renewables alone may not be enough.

In Fred’s Take, Fred Kempe, CEO Atlantic Council, suggests that the world needs “a practical path to a more sustainable energy system that recognises we’re going to need a lot of different technologies and that the approaches and economic implications will vary across geographies. The climate community will [need to] confront the uncomfortable truth that oil and gas will remain a critical part of the mix for the foreseeable future and the fossil fuel industry will need to accelerate the lowering of its carbon footprint.” This is also in line with what the IEA has been proposing for some time now. All-or-nothing measures do not work; instead an “all of the above” approach is going to be needed.

_f600x606_1602493054.JPG)

_f1000x392_1602493237.JPG)