On the road to COP29: what to expect? [Global Gas Perspectives]

The top priority for COP29 is to agree to a new climate finance goal, known as the New Collective Quantified Goal (NCQG). COP29’s president-designate Mukhtar Babayev confirmed that the NCQG is the main priority of the COP29 Presidency. It is for this reason that COP29 has been dubbed a “Finance COP.” But the Summit Action Agenda, announced by Babayev, lacked any direct mention of transitioning away from fossil fuels.

The message from Simon Stiell, UN climate chief, to governments mid-October was that COP29 should be “an enabling COP, delivering concrete outcomes to start translating the pledges made in last year's historic UAE Consensus into real-world, real-economy results”. He called for a “quantum leap” in climate finance – “a new deal between developed and developing countries.”

The top task for this year’s COP is to agree a new climate finance goal to start in 2025. But that will not be easy. For a start, globally money is tight, and climate finance needs are huge and rising. And on top of this there is increasing pressure on richer developing countries, such as China, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, India and Brazil, to step in to help out poorer countries, but this is meeting a great deal of resistance.

Even Europe, the largest contributor to climate finance, is facing problems, with pressure to cut public spending increasing. Both the UK and France have cut their foreign-aid budgets. As Stiell admitted, “it’s hard for any government to invest in renewables or climate resilience when the treasury coffers are bare, debt servicing costs have overtaken health spending and new borrowing is impossible.” A view in Europe is that “rich countries would only step-up funding if China starts paying-up.”

An additional challenge is that many developing countries are calling for more international public climate finance to be provided in the form of grants, rather than loans, something that rich country voters will baulk at. In fact, Indian environment minister Bhupender Yadav said developing countries need more than $5 trillion to meet their climate goals by 2030.

There are signs of convergence on how a new global climate finance goal should be structured and towards a big funding pot – well above $1tn annually – that will include wider sources, such as private-sector investments and loans and “anything else that can be counted,” in addition to public funding. As a climate activist put it, “if they could, rich countries would probably like to count the sun, the moon, and grandpa’s old socks as climate finance too.” Nevertheless, success depends greatly on ensuring that political and economic realities are taken into account. This is expected to go to the wire.

An additional concern -given the uncertainty introduced by the forthcoming presidential elections- is that the US has not yet defined a funding level or a timeline, but has said that it expects contributions from all sources, including from the richer developing countries.

Another priority for COP29 is to agree on the long-awaited rulebook for a new UN carbon market. This appears to have taken a step forward following the approval earlier in October by the UNFCCC Supervisory Body of carbon market safeguards to protect environment and human rights. Under new rules, “developers of projects under the UN’s new Article 6.4 carbon crediting system will be required to identify and address potential negative environmental and social impacts as part of detailed risk assessments,” through the adoption of a new “Sustainable Development Tool.”

The Supervisory Body also agreed on guidance for the “development of carbon-credit methodologies and carbon removal activities aimed at ensuring that emission reductions claimed by projects are credible.” But these still need to gain approval at COP29.

With the Paris Agreement requiring parties to put forward new NDCs every five years, 2025 will be a crucial year for the submission of NDCs and National Adaptation Plans (NAPs). These are expected to enhance ambition across all pillars of the Paris Agreement. As Stiell said: “The new national climate plans due early next year will be among the most important policy documents produced so far this century, as will adaptation plans.”

Babayev confirmed that COP29 priorities include “contributing to transitioning away from fossil fuels in energy systems, in a just, orderly and equitable manner, as governments agreed to do at COP28 last year.” This was a first, but in the recent Bonn climate talks countries struggled to make further progress. A key group, with the unlikely name of “Like-Minded Group of Developing Countries” (LMDCs), which includes China, Saudi Arabia and India, frustrated any discussions on the subject. As a result, not much progress is expected to be achieved this year, despite pressure from Europe.

The Bonn talks also failed to reach agreement on the Mitigation Ambition and Implementation Work Programme (MWP), a key programme to cut emissions and limit warming, forcing Stiell to warn of “a very steep mountain to climb to achieve ambitious outcomes” at COP29.

This will be an implementation COP, with the presidency focusing on turning COP28 pledges into concrete actions. There is an urgent need to secure increased funding for the Loss and Damage, the Green Climate and the Adaptation Funds. Without such increased funding flowing to projects in developing countries, Stiell warned that “we will quickly entrench a dangerous two-speed global transition.” “We need a new climate finance deal.”

The US/China factor

Critical to a deal and the success of COP29 will be the US/China factor – how the world’s top polluters and energy users cooperate. The US top climate diplomat John Podesta met China’s Liu Zhenmin in September and discussed their new targets to cut greenhouse gas emissions by 2035, as well as climate finance.

Podesta pressed China to come up with ambitious plans to cut greenhouse gas emissions by 2035, while Zhenmin pressed the US to “maintain consistency with policies and make concerted efforts with China to cope with global challenges.” They discussed their efforts to tackle methane and nitrous oxide emissions and committed to co-host a summit on these topics at COP29. They also expressed their intention to continue discussion and cooperation in advancing efforts to halt and reverse forest loss by 2030.

Podesta and Zhenmin committed to support Azerbaijan for successful outcomes at COP29, including agreeing a new NCQG on climate finance and making breakthroughs in texts for Article 6 under the Paris Agreement.

However, the global competition between China and the US in energy transition technology, and the related commodity challenge and China’s commanding position in the supply chains for clean energy, require that the two countries find an acceptable level of coexistence in the global energy system.

China will be going to COP29 from a position of strength. It has already met its 2030 renewables targets and it looks as if its greenhouse gas emissions are on the way to peak this year. But it is still rolling out new coal-fired power plants.

COP29 takes place between November 11 to 22, just after the US presidential elections on 5 November, under the shadow of the threat by Donald Trump -if elected- to “withdraw from global climate action.”

World is off track for COP28 renewable and energy efficiency targets

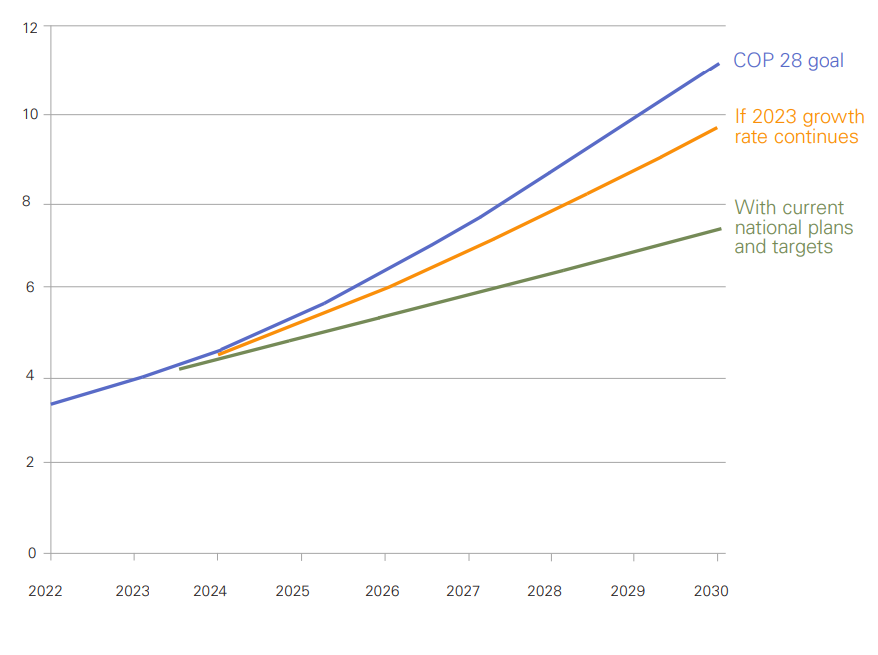

During COP28 about 200 countries committed to a target to triple renewables by 2030, considered to be a critical step towards achieving net zero by 2050. A report this year by the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) warns that despite record growth in renewables in 2023, current national plans will only deliver half of the growth needed to achieve this target (see figure 1).

Figure 1: Renewable energy projections

Source: IRENA

IRENA added that annual investments in renewables are just over a third of the $1.5 trillion needed each year until 2030. The IEA also warned that meeting COP28 goals requires a doubling of clean energy investment by 2030 worldwide. With deep divisions still persisting on agreeing a new climate finance goal, NCQG, achieving the 2030 renewables target remains a challenge.

IRENA also said that little progress has been made in boosting energy efficiency, still stuck at an improvement rate of 2%. The needs to double to at least 4% annually through 2030 in order to meet the COP28 target.

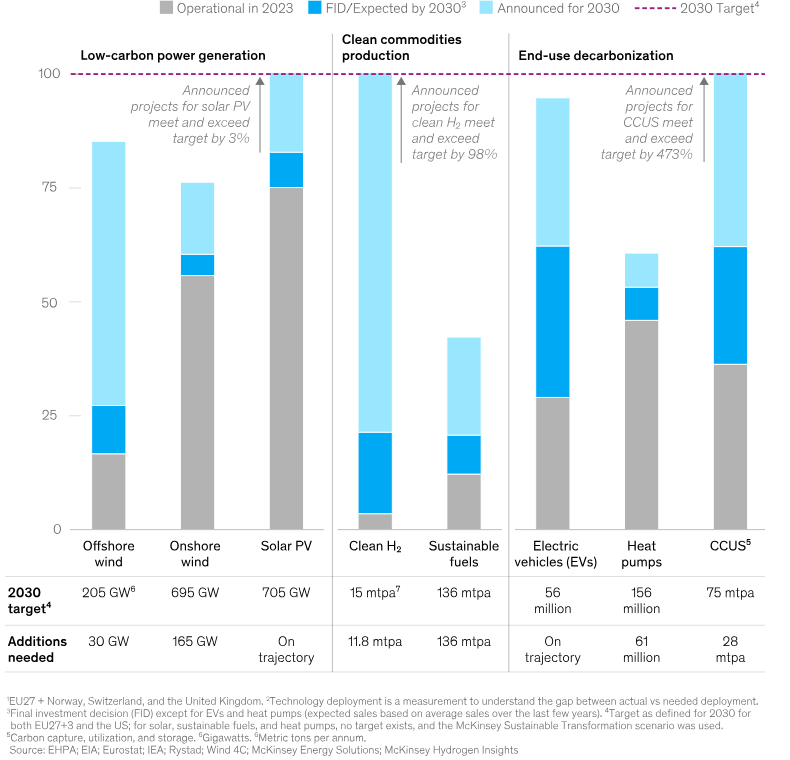

These challenges were confirmed in a timely new report, The energy transition: Where are we, really?, released by McKinsey Global Institute in August. This sheds light on the current status of the energy transition in the US and Europe based on assessing “the alignment between ambitious climate targets and actual progress on the ground.”

The report warns that “many clean energy projects touted as signs of progress on decarbonisation remain unfinalised, creating a ‘reality-gap’ between the perceived uptake of new technology and the actual capital invested.” It states “across several key technologies, clean hydrogen and carbon capture utilisation and storage (CCUS) were found to have the widest gap between the number of projects planned and those really taking shape” (see figure 2). Many projects have not reached their final investment decisions, the analysts say, and are at risk of being cancelled or scaled back.

Figure 2: Technology deployment pipeline in EU and the US

Source: McKinsey

The question remains whether the world’s much-needed commitments can be translated to action. McKinsey’s analysis of targets and announcements highlights a potential disconnect between climate ambitions and what is likely to be achieved in practice – at least based on the current course and speed.

McKinsey concludes that even though a lot of progress has been made since the 2015 Paris Agreement, “at the current pace Europe and the US risk missing important 2030 climate targets across critical technologies.”

“Right now, we're only at about 10% of the deployment of ‘physical assets’ -technologies and infrastructure- that we will need to meet global commitments by 2050. This is not an abstract dollar number, or goal, or theoretical pathway. It’s the physical world that exists around us today. So, despite all the momentum, we’re still in very early stages of the energy transition.”

Facing this hard truth, innovation and policy resets will be needed, including the pace of transitioning away from oil and natural gas.

Despite the progress made by renewables, they are not growing fast-enough to keep-up with the growth in global energy demand resulting from improving living standards, increasing cooling needs and AI data centers.

Evidently, during the energy transition oil and gas will continue to be important to the global energy mix, especially as, despite massive investments, the penetration of renewables in sectors other than electricity is very low.

As Energy Institute’s Statistical Review of World Energy has shown, globally, electricity demand grew by 2,5% in 2023, much the same as in 2022, and comprised 17,4% of global primary energy demand, only marginally up on the 17,3% in 2022. At this rate, energy transition will be a long-drawn process.

The bottom line is that natural gas is hard to replace and will have a key role to play in global energy consumption all the way to 2050 and likely beyond. But more effort should be made to reduce emissions – now at an all-time high – and make natural gas use as efficient as possible. Replacing coal with natural gas and eliminating methane emissions must be a priority.

At a joint meeting in June, the IEA and the COP29 Presidency focused on turning COP28 pledges to cut methane emissions into action, Babayev said “tackling methane emissions will be essential to delivering the COP29 Presidency’s plan to enhance ambition and enable action…through finance and technology so that we can deliver our promises.”

Maintaining oil and gas reserves and production to support this demand is critical to global energy security. The oil and gas majors have been making this point for a while, but, importantly, major international banks and lenders are coming to a similar conclusion.

In the meanwhile, COP29 is expected to be a lower-profile summit than COP28. Many are already “looking ahead to COP30 in Brazil, which – given the submission of new NDCs in 2025 – is anticipated to carry greater significance.”