Opportunities and risks in the E Med [NGW Magazine]

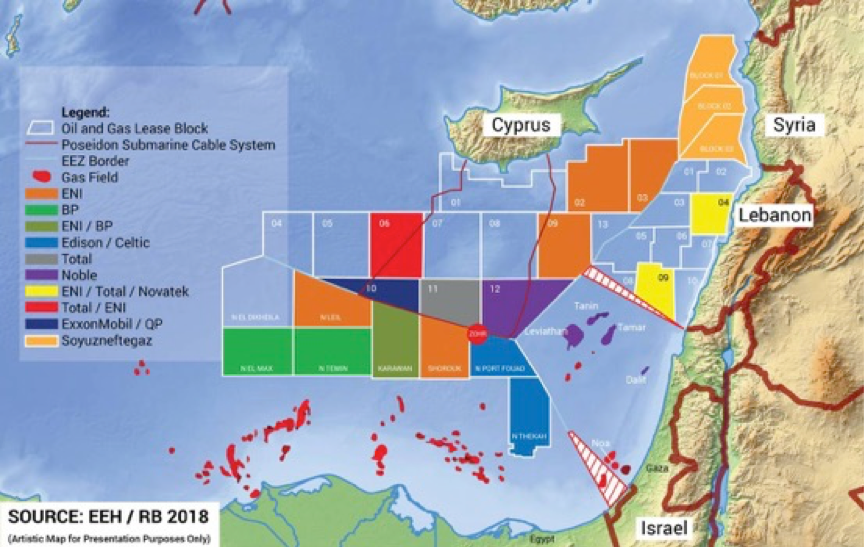

Ever since the discovery of giant gasfields Tamar and Leviathan off Israel and Zohr off Egypt, the eastern Mediterranean has been a focus of attention for the international oil companies. Anglo-Dutch Shell, US ExxonMobil, UK BP, French Total and Italy’s Eni all have interests in the region (Figure 1).

Figure 1: IOC interests in the eastern Mediterranean

But while Egypt has been forging ahead with developing its gas-fields and liberalizing its gas sector, Israel and Cyprus have been struggling to secure export markets and Lebanon is yet to start production.

However, given the increasing appetite of global markets for LNG, is this about to change? Will local challenges and competitive global gas prices be overcome, unlocking the promising gas potential of the eastern Mediterranean?

A panel at Gastech in Barcelona in September considered the investment opportunities and risks:

- The extent of proven and probable reserves in the eastern Mediterranean basin

- Gas exports - by ship or by pipeline?

- Economics - can eastern Mediterranean gas be exported at competitive prices, despite the proposed cost of evacuation routes?

- Will it be a unifying commodity? Will the potential rewards of gas exports from the region allow the different players to bridge political divides?

- Social licence: new entrants and incumbents alike need to be aware of the environmental and social impact of exploration and production activity in the region.

Interest in the eastern Mediterranean has increased during the last ten years with the discovery of major gas-fields such as Tamar, Leviathan and the giant Zohr field in Egypt. These have opened up major opportunities for new discoveries, but also for oil and gas investments in the region. But these come with risks.

Huge potential

The eastern Mediterranean is a true hot-spot for the oil and gas industry. A total of about 4,000bn m³ gas resources have been discovered so far, and there is still huge potential for more discoveries, with an estimated 2,800-8,500bn m³ yet to find. This is attracting strong interest by the industry.

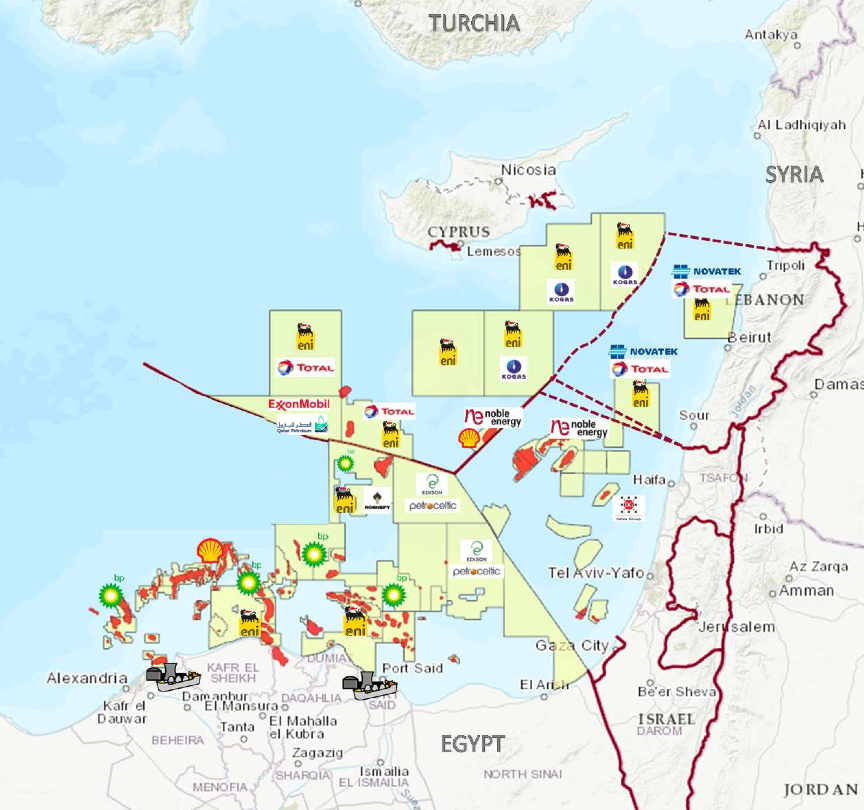

Figure 2: Eni’s offshore blocks

The development of this potential requires full use of existing facilities and building transportation infrastructure. Once in place, this can act as a catalyst to develop small discoveries; but regional markets need further development if the resources of the region are to be fully commercialised at home. However, there is more gas available than can be used locally.

Export of this gas to Europe and possibly Turkey requires LNG facilities and pipelines (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Eastern Mediterranean LNG plants and pipelines

The proximity of the region to the EU offers obvious advantages, including a market for LNG exports and a strong financial market; there are however regulatory risks, according to consultants AD Little (see box).

Egypt in particular has the potential to become a hub for gas export, using idle LNG plants, which can be easily extended to accommodate more gas as more discoveries are made (see separate feature). Furthermore Italy could play a role as transit hub for natural gas towards the EU. Such a hub could enhance European energy security, provided gas can be exported at competitive prices.

A prerequisite for further integration and realization of the full gas potential of the eastern Mediterranean is geopolitical and regional stability through resolution of regional conflicts. The EU could play a central role in this by putting European diplomacy into action.

Developments in Lebanon

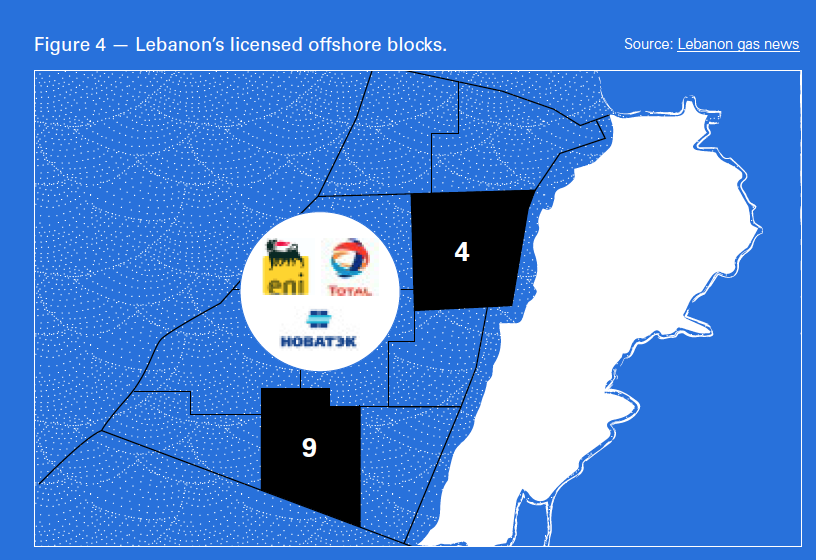

In January this year Lebanon signed its first offshore oil and gas licences for blocks 4 and 9, with a consortium comprising French Total, Eni and Russian independent, Novatek (Figure 4). The exploration process has started, with drilling expected in 2019.

Substantial progress is being achieved, including the preparation of the required technical and environmental studies as well as logistics, ahead of drilling works. The first well will be drilled in block 4, and another well later in block 9.

The exploration and production contracts stipulate that four in every five people employed by the licensees should be Lebanese, and that local suppliers and contractors have priority.

Developing local capabilities in the oil and gas sector is a key objective, so that Lebanese institutions have the capacity to implement their respective mandates.

Lebanon is also pursuing co-operation with countries in the region and the EU. This includes technology transfer in the oil and gas sector and discussion on environmental issues.

The energy ministry plans to import LNG as an interim measure over the next 10 years, until Lebanon is able to produce its own gas. This will be used primarily for the power sector.

Lebanon’s priority is to make use of any discovered resources to satisfy the growing local market for natural gas, with the potential for exports if the volumes allow.

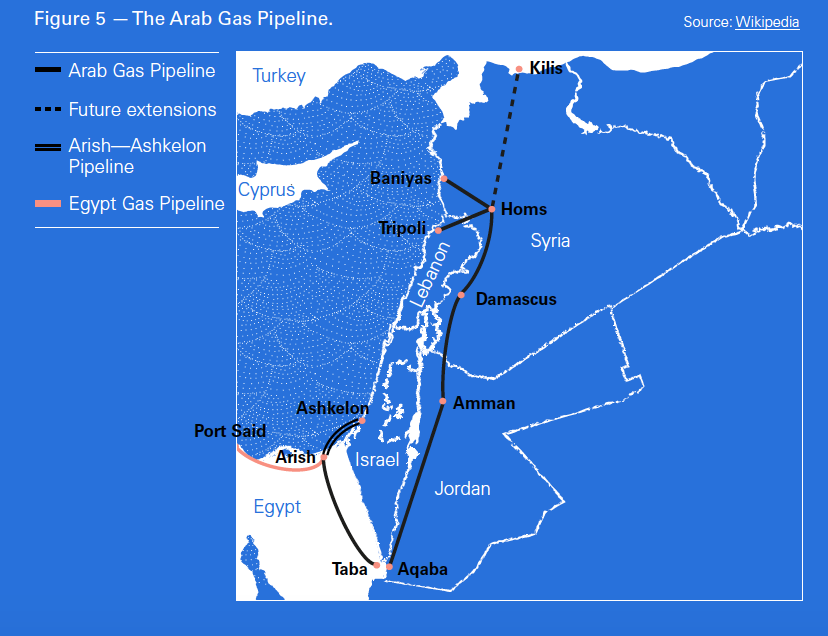

Even though it is too early to think about such exports, the LPA has been considering all options, including the now idle Arab Gas Pipeline (Figure 5).

With a total length of 1,200 km, it was originally built to export Egyptian natural gas to Jordan, Lebanon and Syria, with a subsea branch to Israel. What makes this attractive to Lebanon is that it is readily available for regional exports of gas.

Lebanon’s second offshore licensing round

Following the success of the first round, Lebanon is now proceeding with the launch of a second offshore licensing round, offering additional offshore blocks.

The objectives of the second licensing round revolve around:

- Accelerating exploration activities in Lebanese waters

- Increasing attractiveness of the Lebanese waters and promoting competition

Before the official launching of the tendering process, all the documentation pertinent to it will be published on the website of the LPA. In particular, this documentation includes:

- The tender protocol defining the conditions of the bid round, the biddable parameters and the evaluation methodology

- The model exploration and production contract

Companies interested in taking part in the second bid round are required to participate in a prequalification round that sets the minimum technical and financial conditions for operators and non-operators. Prequalified companies will have at least six months to form consortia, composed of at least three companies each and to place their bids. The Lebanese authorities will evaluate the received bids according to the tender protocol. Signature of the exploration and production agreements will then follow later in 2019.

Israel

In Israel Tamar has proved to be a great success, having secured a captive domestic market. But the same cannot be said for Leviathan. Noble Energy and its partners are in the process of developing phase 1A of the project, with first-gas expected end of 2019, destined for the Israeli domestic market. This is underpinned by a gas sales agreement secured earlier in the year to supply 45bn m³ gas to Jordan’s state generator Nepco over 15 years –not a popular deal in Amman – but more buyers are needed.

Energean is also proceeding fast with development of the Tanin and Karish fields, having taken final investment decision earlier in the year, backed by gas sales agreements and third-party financing.

With 625bn m³ of gas, Leviathan also needs to secure export markets, but options such as the EastMed gas pipeline (EMG) to Europe, exports to Turkey and more recently to Egypt are all proving to be challenging commercially and politically.

Noble and Delek late September bought a controlling 39% stake in EMG, on order to transport gas south from their Israeli reserves; but the now-idle Egyptian export line crosses Sinai. It was the target of numerous successful attacks in the past.

It is this lack of export routes that has been thwarting attempts by Israel to attract international majors to its offshore licensing rounds. No exploration has taken place in Israel during the last five years.

Cyprus

Having discovered the 127bn m³ Aphrodite gasfield in 2011 and the Calypso gas-field earlier this year in block 6, Cyprus is still beset with threats from Turkey, whose naval intervention earlier in the year stopped Eni from drilling in block 3. ExxonMobil’s very promising block 10 offshore Cyprus (Figure 1) may reverse the flow of disappointing news. But much hangs on restarting negotiations, following discussions at the UN in New York in September, for another attempt to find a solution to Cyprus problem this year.