Pakistan: an ocean outlet for Central Asian gas? [Gas in Transition]

In its June tender for spot LNG state-owned Pakistan LNG Ltd (PLL) sought six shipments for delivery in the fourth quarter of 2023. But, when the tender closed on June 20, it had received no bids. The spot purchases were intended to complement Pakistan’s three long-term contracts for LNG during the peak winter period, when gas demand for power generation and for residential space and water heating is high.

|

Advertisement: The National Gas Company of Trinidad and Tobago Limited (NGC) NGC’s HSSE strategy is reflective and supportive of the organisational vision to become a leader in the global energy business. |

The failure of the tender was primarily due to the country’s parlous economic situation, poor credit standing and very limited foreign currency reserves. Suppliers and their bankers have to deal with an energy system in which sovereign guarantees are a necessity because of the prevalence of state ownership and below-cost energy sales prices.

With the state finances in a mess, sellers may have been waiting for the outcome of negotiations with the International Monetary Fund over the measures needed to secure a financial bailout. A staff-level pact – essentially a bridging loan of $3bn to avoid default – was finally agreed June 30.

Winter crisis

The country’s previous tender for spot LNG was launched in August 2022, and sought 72 shipments over a six-year period. It, too, drew a blank.

The lack of spot supplies in the run up to winter was compounded by lower than contracted term deliveries to the country’s two LNG import terminals, the BW Integrity and Engro Elengy floating storage and regasification units (FSRUs).

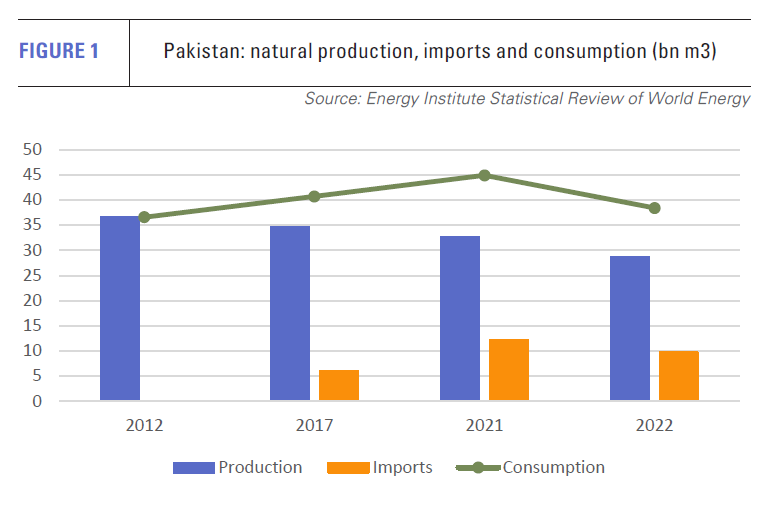

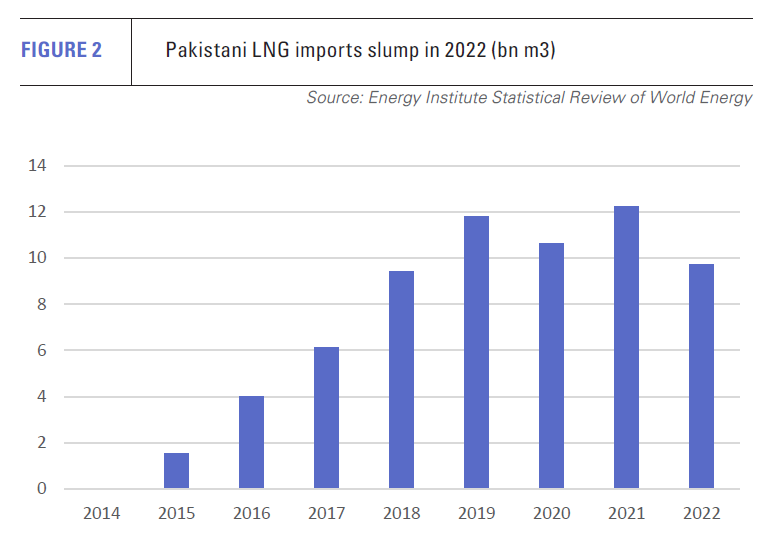

As a result, LNG imports slumped by 20.6% year on year to 9.7bn m3 in 2022, according to data from the Energy Institute Statistical Review of World Energy 2023 (see figure 1).

The fall in imports was compounded by declining domestic gas production. This has been dropping for years, from 36.6bn m3 in 2012 to 32.7bn m3 in 2021. However, the decline accelerated in 2022, with output down 12.2% year on year to 28.7bn m3 (see figure 2).

Slumping gas supplies

The double whammy of falling gas production and imports meant Pakistan’s total gas supplies fell by 14.5% from 44.9bn m3 in 2021 to 38.4bn m3 in 2022, with much of the drop occurring at the end of the year. The impact of the resultant gas shortages was felt in the power sector in particular, resulting in extensive power blackouts and load-shedding during the 2022-23 peak winter period.

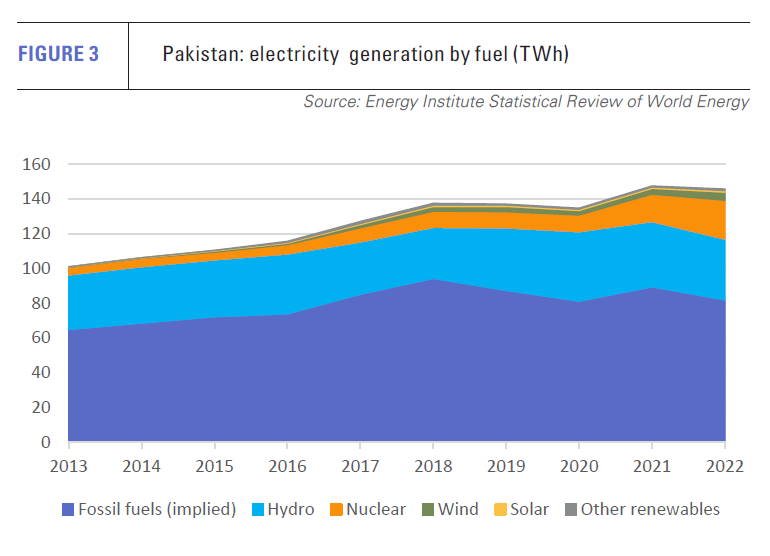

The shortage of gas was not helped by reduced hydroelectric power production, slow growth in the installation of wind and solar capacity, and equally slow growth in coal-fired power generation. Total power generation fell to 145.8 TWh in 2022 from 147.6 TWh in 2021 (see figure 3).

With the problems continuing into mid-2023, it is widely anticipated that the 2023-24 winter will see an energy crisis even more severe than in the previous winter. However, the government has waved away the concerns, claiming the problems will be avoided by a resurgence of gas availability. This looks unlikely.

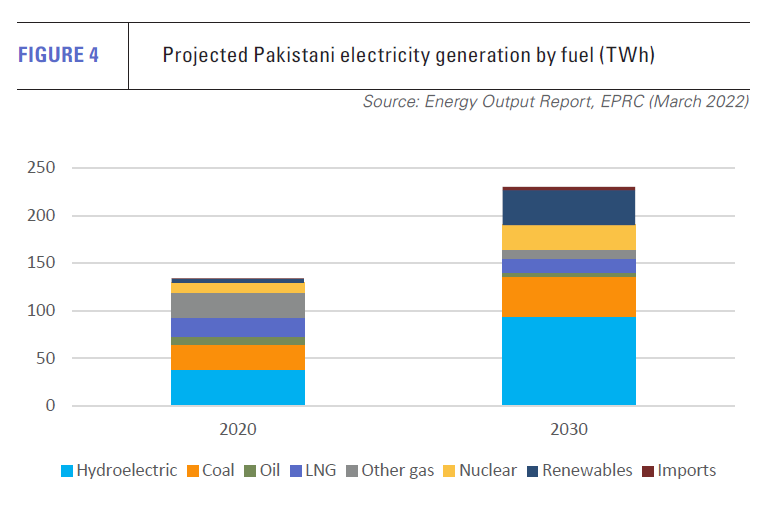

Domestic gas availability is not expected to increase, rather the reverse, with the decline in output set to continue. Last year, the government’s Energy Output Report to 2030 projected that domestic gas production would fall by more than a third from 2020 to 22.5bn m3 in 2030 (see figure 4).

Domestic gas availability is not expected to increase, rather the reverse, with the decline in output set to continue. Last year, the government’s Energy Output Report to 2030 projected that domestic gas production would fall by more than a third from 2020 to 22.5bn m3 in 2030 (see figure 4).

The report argued that to offset this fall and meet projected demand growth, about 19.8bn m3 of imports would be needed in 2030. This would be almost double the 2020 level, and would be higher still, if the substantial projected reduction in energy losses is not achieved.

The Energy Output Report noted that securing this amount of new gas would require the provision of at least 6.2bn m3/yr of additional LNG import capacity, as well as the construction of gas storage capacity and a north-south gas pipeline network to deliver LNG to the north. The conclusions and underlying projections in the report were reiterated in an analysis of natural gas supplies issued by the Ministry of Planning in June.

Looking north for gas

The great majority of Pakistan’s LNG currently comes from Qatar, which provided 8.6bn m3 out of a total 9.7bn m3 of LNG imports in 2022. Nigeria was a distant second, supplying 0.4bn m3.

However, in early June, Islamabad signed a government-to-government agreement with Azerbaijan under which the latter’s state-owned energy company Socar will each month offer PLL the option of buying a shipment of LNG at a price below the prevailing global price. Commenting on the deal the Pakistani Minister of State for Petroleum, Musadik Malik, said this would help avoid energy shortages in the coming winter.

Details of the deal remain to be announced, including the volume and pricing arrangements. The deal has nevertheless already caused a rift in the government with the resignation of Shahid Khaqan Abbasi, a former petroleum minister and prime minister. He argued that the deal should have involved private companies to secure better terms, rather than a government-to-government arrangement.

Even if the deal proves to be of limited efficacy, it demonstrates Islamabad’s increasing emphasis on Central Asia as a key source of the country’s future energy supplies. The switch to Central Asia would also mark a shift in the mode of delivery of additional imports, with gas being imported through pipelines rather than LNG terminals.

Not only that, but Islamabad believes it could lead to Pakistan becoming an exporter of LNG. In June, Musadik Malik suggested gas could flow south from Central Asia through a North-South pipeline system, with part of the supply being exported as LNG from terminals to be built at a proposed international energy hub in Gwadar.

He told a press conference that gas could be sourced from Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan. He added that the liquefaction terminals could be built and financed by Chinese or European companies for export to their own markets, although without giving any details on how the ownership and operation of the terminals would work.

New hope for TAPI?

One obvious candidate to deliver the piped gas supplies would be the long-mooted Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India (TAPI) project. As currently envisaged, TAPI is intended to supply up to 33bn m3/yr of gas from the giant Galkynysh field in Turkmenistan to Pakistan and India. A high-level delegation from Turkmenistan visited Islamabad to discuss the project in early June, with a joint implementation plan to speed up work on the project being signed in the presence of Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif.

The TAPI deal has been a long time in the making. Although the pipeline in Turkmenistan has reportedly been completed, the section running through Afghanistan effectively remains to be started because of security, financial and logistical issues.

Deliveries of gas from Turkmenistan to Pakistan have in fact started, but in the form of LNG trucked from the Turkmen border through Afghanistan. According to local media reports an opening ceremony for deliveries by this route took place in late April in southern Afghanistan’s Kandahar province when a convoy of 50 LNG transporters arrived on their way to Pakistan.

Afghanistan approved construction of the section of pipeline running through its territory in June. However, securing finance for the project will be problematic, given multilateral lenders’ concerns over the Taliban government’s approach to issues such as women’s rights.

These issues, together with security concerns over the transit arrangements, will also make international investment in the proposed LNG export capacity in southern Pakistan problematic, especially for European investors.

While China could potentially wire together the arrangements needed to build both the pipeline in Afghanistan and LNG export capacity in Gwadar, the economics of the route may be questionable, compared with the existing routes by which China receives Turkmen and other Central Asian gas. Moreover, Chinese investment in Pakistan’s energy sector has been far from trouble free, for instance in terms of the payment and operating issues relating to its involvement in the country’s independent power producer projects.

Afghanistan thus makes the viability of exporting Central Asian gas through Pakistan problematic. The supply of gas from Iran’s vast fields to Pakistan would be easier in logistical terms, but remains politically problematic. The proposed Iran-Pakistan (IP) pipeline could supply substantial amounts of gas to both Pakistan and export markets, but is currently ruled out by Islamabad because of the threat of US sanctions.

Afghanistan thus makes the viability of exporting Central Asian gas through Pakistan problematic. The supply of gas from Iran’s vast fields to Pakistan would be easier in logistical terms, but remains politically problematic. The proposed Iran-Pakistan (IP) pipeline could supply substantial amounts of gas to both Pakistan and export markets, but is currently ruled out by Islamabad because of the threat of US sanctions.

The Central Asian LNG export project has many attractions for Pakistan, not least because the country has a relatively small gas market. The export terminals would increase the volume and lower the unit cost of gas delivered through the north-south pipeline, generate fees from the exporters, and reduce the necessity of selling gas to the Indian market.

LNG exports could thus make projects such as TAPI more economically viable. However, implementing the project will be far from easy because of the range of political, financial and regulatory issues both in Pakistan and Afghanistan. Offering an ocean outlet for Central Asian gas may have many attractions, but it also faces many problems.