Pakistan’s power grab [NGW Magazine]

Electricity demand is rising in Pakistan as the population and the economy continue to expand. But even so the country’s latest long-term power plan seems to have taken too optimistic a view of its future prosperity.

The state-owned National Transmission and Despatch Company (NTDC) published its Indicative Generation Capacity Expansion Plan (IGCEP) 2047 earlier this year and it shows a very toppy demand growth and generation demand forecast.

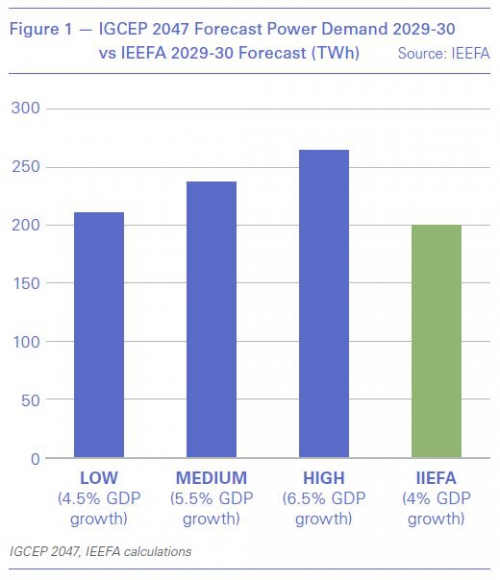

IGCEP factors in gross domestic product (GDP) growth forecasts for three scenarios: 4.5% (low), 5.5% (medium) and 6.5% (high) for 2047. The April plan assumes the central case, namely that GDP grows from 4% in 2020 to 5.5% by 2025 and stays there for the next 22 years. The results are divided into two time periods: 2020-30 and 2031-47.

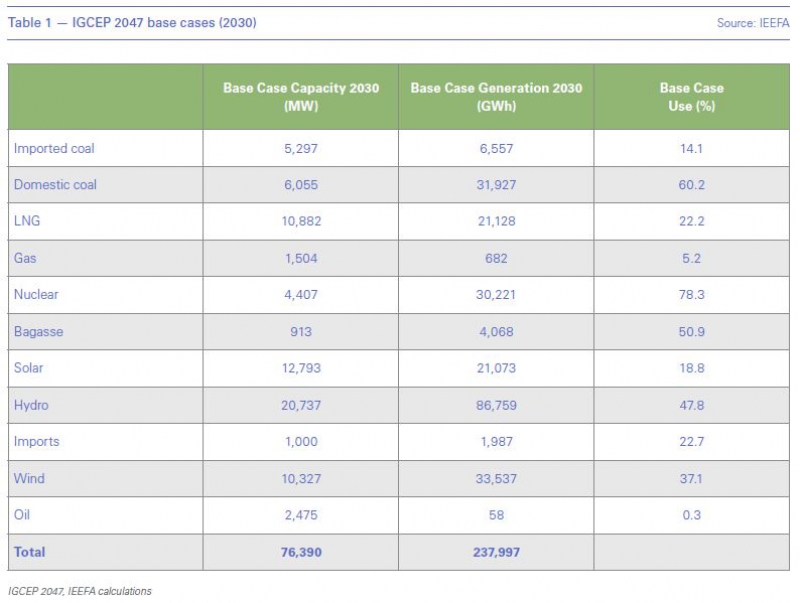

The base case result shows that peak demand increases from 27.13 GW by end of fiscal 2020 to 43.82 GW by 2030. That means 76.40 GW is required, the excess being offset by the intermittency of renewables. Of that, the share from variable renewable energy (VRE) resources has been taken as 10.33 GW of wind and 12.79 GW of solar.

In order to mitigate the intermittency of VRE and ensure substantial reserve provisioning, 4.87 GW of open cycle gas turbines (OCGTs) that run on regasified LNG (RLNG) and 6.10 GW of steam turbine (STs) that run on local coal (Thar) and 20.74 GW of hydro need to be built, according to IGCEP.

Similarly, the plan envisages that in order to meet the projected demand of 103.10 GW by 2047, a total of 168.25 GW of nominal generation capacity is required.

By the end of financial year 2018-19, the total installed generation capacity in the country reached 35.96 GW of which 27.17% was hydro, 63.54% were thermal plants which comprise natural gas, local coal (thar), imported coal, residual fuel oil (RFO) and regasified LNG (RLNG) technologies; 5.56% renewable-based plants which include solar, wind and biomass based technologies, and 3.74% nuclear plants.

The fleet generated 122.542 GWh in 2018-19, of which hydro accounted for 26.5%; thermal plants for 62.24%; nuclear for 7.40% and renewable energy for 3.86%.

RLNG based power to slow down by 2030

The plan expects RLNG-based power to slow by 2030 and beyond as Pakistan uses instead more domestic coal and hydro. The RLNG based plants decline from 2020 to 2047, from 26% to 11% in 2025 but just 1% beyond 2034.

The forecast runs contrary to the recent trend. In the past few years, the south Asian country has been increasing its RLNG-based power generation and the government on many occasions has said that RLNG will be an important part of the energy mix.

Pakistan became an LNG importer in 2015 and has two terminals in operation, both at Port Qasim near Karachi. According to reports, the country has imported 19mn metric tons of LNG since 2015 but with a sharp increase over the years. In 2019, Pakistan imported 7.57mn mt of LNG, as against a little over 1mn mt in 2015.

Pakistan's annual RLNG-fired generation rose to 28.1 TWh last year, from 27.8 TWh in 2018, according to data released by the country's regulatory authority, Nepra. But IGCEP sees the combined generation from power units that run on RLNG under different demand scenarios in the range 20.7-21.8 TWh/yr. The IGCEP’s base-case scenario has RLNG-fired output almost in the middle, at 21.1 TWh/yr.

Although the share of RLNG in the power mix is expected to decline, RLNG based power capacity is still set to rise to 10.88 GW by 2030 under IGCEP's base case, from about 6.79 GW this year. This will allow the country's LNG-fired fleet to meet drops in variable renewable generation output. RLNG-based capacity is set to go up further to 30.58 GW by 2047.

“It is pertinent to note that there is an increasing trend in the installed capacity of the RLNG based plants whereas RLNG’s share in the energy mix is reducing, and eventually falls to only 1% in 2047. This increase in the installed capacity of RLNG based plants is thus to cater to the intermittencies of solar and wind power plants,” IGCEP said.

Plants running on imported coal see a drop in their contribution to the overall generation mix, from 18% in 2020 to only 1% by 2047. Conversely, the share of wind and solar in the overall energy mix goes up, from about 3% in 2020 to 23% in 2030. Beyond 2030, both solar and wind plants lose out to domestic coal-based plants with higher capacity.

In addition to the share of the RLNG and coal fired plants, the plan says the share of domestic gas fired plants in the generation mix will also drop, from 14% to just 2% in the next five years. Pakistan’s local gas output has stagnated: there have been no major discoveries in over a decade.

Stranded RLNG assets

The plan has come under criticism as analysts believe the forecast is an over-estimate. The high level of planned capacity compared with the expected demand is partly due to the addition of renewable energy capacity. Wind and solar are always going to produce a lot less than their nameplate. But it is also due to over-capacity.

US-based Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA) said early-September that Pakistan risks locking itself into building more power capacity than it needs as a result of over-optimistic demand growth forecasts that do not take into account the impact of Covid-19 pandemic. This over-optimism risks leaving imported coal and RLNG plants stranded as these will be the first in the firing-line.

The IEEFA report said GDP growth estimates were on the higher side given IMF’s 2019 GDP growth assessment of just 3.3%. In addition, the IGCEP forecasting was completed before the Covid-19 pandemic pushed the world into an economic slump and made a nonsense of the earlier forecasts.

IEEFA is especially critical of IGCEP modelling addition of 20 GW of RLNG-fired power capacity between 2030 and 2047 which is hardly used at all by 2047, except as reserve capacity to complement wind and solar.

“The idea that a total 31 GW of LNG-fired power is needed to balance the intermittency of 37 GW of wind and solar power in 2047 is, at best, wildly inaccurate, especially given how cheap energy storage solutions will be by that time. In reality, tens of thousands of megawatts of LNG-fired power would be built at great cost and would then sit idle, stranded under this scenario,” IEEFA said.

“If Pakistan’s power capacity and generation figures resemble this model at 2030, this will be as a result of the nation building too much thermal power capacity,” IEEFA said. “With the base case using the over-estimated medium power demand growth forecast, there is a significant risk that actual utilisation rates for thermal power will be even lower, and stranded assets even higher than predicted by this model.”

Shift away from imported fuel

IEEFA energy finance analyst Simon Nicholas believes Pakistan has decisively shifted from a future of imported fossil fuels – coal and LNG – to one based on domestic sources of power. That means renewable energy, domestic coal and hydro.

“Energy security is a concern as is the cost of fossil fuel imports, which have been made even more expensive by the weakened Pakistan rupee. I think it is likely that power projects that use imported fossil fuels will be the ones to be abandoned first for energy security and cost reasons,” Nicholas said. “Hydro and domestic coal-fired power are not cheap but they improve energy security. Renewable energy is already the cheapest source of new power generation in Pakistan.”

IGCEP underestimates renewables

Under the base case, IGCEP includes solar additions between 2030 and 2047 but the overall contribution of renewables to power capacity drops from 31% in 2030 to 23% in 2047. The forecast of reduction of share of RLNG and renewables in the overall energy mix and focus on domestic coal and hydro is justified by IGCEP by highlighting the need for the ‘indigenisation’ of Pakistan’s power mix.

“The lack of any wind power additions after 2030 is particularly strange given Pakistan’s wind resources, the fact that renewables are already the nation’s cheapest source of new power generation and the certainty that renewable energy will only get cheaper into the future,” IEEFA said.

The lack of any proposed government renewable energy target beyond 2030 being incorporated into the IGCEP model is interpreted as meaning the focus on renewables will weaken significantly beyond that year. IEEFA believes this highly unlikely, given the technology’s continually declining cost.

Despite the lack of a post-2030 target, IEEFA said it would have made far more sense for the IGCEP to model at least the maintenance of a 30% renewable energy contribution to the overall mix as renewable costs will probably continue to decline sharply.

According to IEEFA, a move away from reliance on imported fossil fuels makes sense, but the IGCEP is not putting anywhere near enough emphasis on wind and solar power which would improve energy security at a lower cost.

“Modelling declining contribution from renewables post-2030 makes the IGCEP look very out of touch with today’s power trends,” Nicholas said, adding indigenisation of power through domestic coal-fired power will be expensive. Renewable energy can reduce reliance on fossil fuel imports far more cheaply than coal power.

“The neglect of cheap renewables and focus on expensive coal power shows that the IGCEP further fails to live up to the government’s affordability principle,” said Nicholas. “The introduction of large amounts of domestic coal power will also lead to a significant increase in the overall carbon emissions of Pakistan’s power system according to the IGCEP, not decreases. The IGCEP fails the government’s sustainability principle as well as one of its stated goals of reduced carbon emissions,” he said.