Perenco carves out Gulf of Guinea LNG niche [Gas in Transition]

Perenco took the final investment decision on its $1bn project to develop a small LNG plant in Gabon in February. Following on from its success in developing the Hilli Episeyo floating LNG (FLNG) scheme in nearby Cameroon in 2018, it is again demonstrating that small associated gas reserves can be tapped to produce liquefied gas, providing host governments are sufficiently supportive.

The new LNG plant will be built at Cap Lopez along with a new oil terminal, near Gabon’s second city, Port-Gentil. It will have a production capacity of 700,000 mt/year, making it the smallest LNG export scheme in Africa. It is expected on stream in 2026.

Gabon’s Ministry of Oil and Gas and other regulators approved the project’s development in December 2022. Perenco has not said what form the project will take, but it appears to be a small onshore plant, although FLNG is also possible. While the LNG plant and new oil storage facilities are being built at the Cap Lopez terminal, a very large crude carrier with storage capacity of 2mn barrels is being deployed to maintain oil exports.

Perenco General Manager, Benoît de la Fouchardière said: “We are pleased to be investing to help meet Gabon’s future energy demands, supporting the country in reducing emissions, and delivering a project that will also create hundreds of direct and indirect employment opportunities.”

The emphasis on non-financial domestic benefits suggests that it was the company’s commitment to domestic energy supplies that helped bring the government on side. NJ Ayuk, the chairman of the African Energy Chamber (AEC), added: “We consider this a critical step forward towards achieving energy security and fuel independence in Africa.”

Domestic fuel supply

Under its agreement with Libreville, Perenco will produce 20,000 mt/yr of butane by 2026, sufficient to make the country self-sufficient in the fuel. The company was already committed to producing 15,000 mt/yr of LPG a year at the Batanga plant in Ogooue-Maritime province. The Batanga plant is scheduled to come onstream in the third quarter of this year and will reduce the country’s LPG imports by more than 50%.

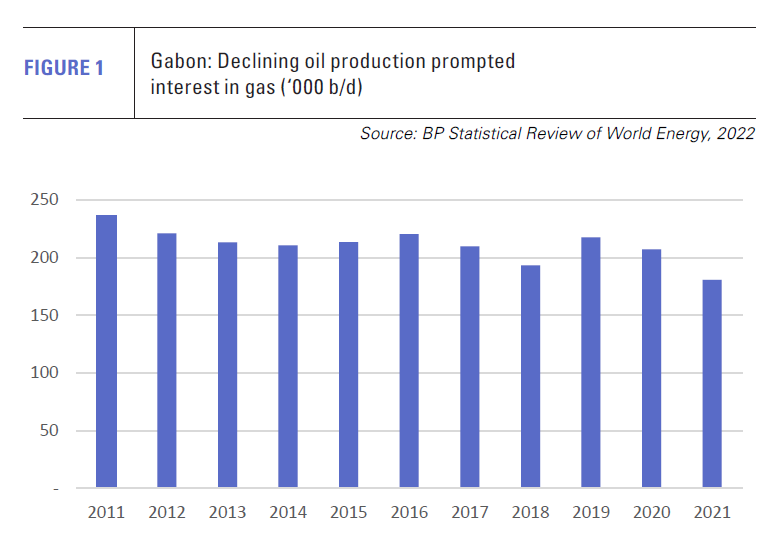

The government is keen to diversify its economy and reduce energy imports, in large part because of falling oil revenues. Gabonese oil production fell from 370,000 b/d in 1997 to 180,000 b/d in 2020 (see figure 1). However, new investment terms for redeveloping mature fields and encouraging the development of marginal fields were included in the 2019 Hydrocarbons Code and had already resulted in a partial recovery in oil production to 200,000 b/d by early 2023.

Perenco is the biggest oil and gas producer in Gabon, operating a range of onshore and offshore blocks and two floating offshore storage and offloading vessels (FPSOs), but has not specified which fields will supply the LNG plant and whether they will only be those under its control.

The company acquired Cap Lopez as part of a wider deal with TotalEnergies that included non-operated assets in seven Gabonese fields in 2021 for $350mn. In July 2019, Perenco was awarded the licence for the Olowi field, which is estimated to hold 850mn ft3 of natural gas.

Most recently, at the end of April, it secured more upstream assets in Gabon, including on the producing Limade, Turnix, Moba and Oba fields, as the result of an asset swap with Tullow Oil. Perenco said that the deal would give it a better balance of production and appraisal and exploration assets, although it did not say if the agreement was designed to provide access to additional gas reserves.

Government backing

According to government figures, Gabon has proven natural gas reserves of 1.02 trillion ft3 (28.9bn m3), mainly in the form of associated gas and almost all of it offshore. However, little effort has been put into appraising the extent of existing discoveries as a result of their apparent limited size and because of the lack of a significant local market. Some sources suggest that the reserve figure could be 3-5 trillion ft3. Moreover, the country lacked a legal and tax regime to incentivize gas exploration for many years because of a lack of official interest in developing marginal gas reserves.

However, lower oil income appears to have pushed the government into a change of heart. The new Hydrocarbons Code sets out a ten-year gas sector plan, including ambitions for boosting domestic gas consumption and developing LNG export capacity. A Presidential Gas Task Force was set up in 2021 to supervise the sector’s development and identify possible investors.

Upstream reforms included in the new Code have encouraged greater investment in exploration, which could reveal more gas for LNG production. New licensing rounds for offshore acreage are also being held for the first time since 2014. Finally, the government’s new Transformation Acceleration Plan requires more gas to be produced for domestic consumption and also for export, if possible.

Expanding infrastructure

The Gabonese gas sector is currently very small, but Perenco supplies natural gas to two small power plants in the country’s two biggest cities, Libreville (75 MW) and Port-Gentil (105 MW).

It has also signed a memorandum of understanding with the Gabon Power Company to supply gas for a power plant in the south of the country at Mayumba with initial capacity of 21 MW, potentially rising to 50 MW in the future. This will allow Gabon Power to develop its electricity distribution network in the area, including a 90kV transmission line to the city of Tchibanga.

A new 1200-MW gas-fired generation plant is also planned at Owendo close to Libreville, where a 128-MW gas-fired station already exists. The plant will be built and operated by a Wartsila consortium for 15 years before being transferred to the state. The plant will be powered by gas which is currently flared.

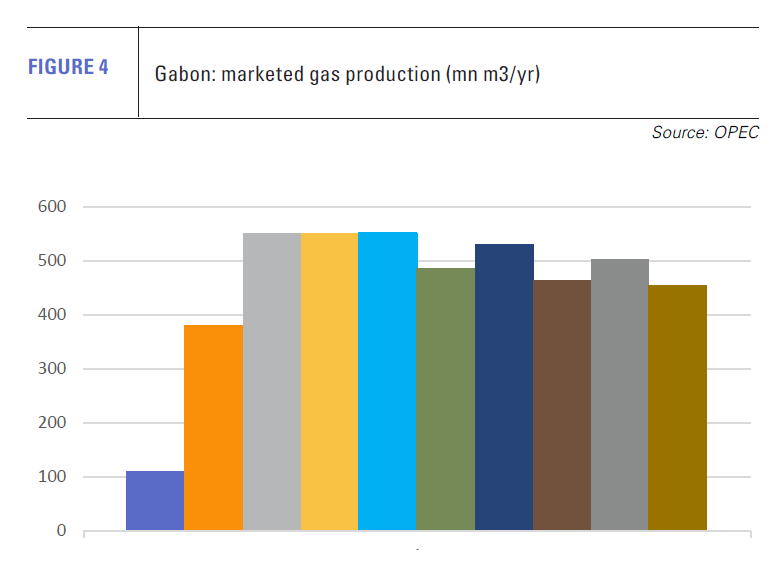

It is difficult to obtain current figures for marketed gas, but OPEC data shows 453.9mn m3 (16bn ft3) in 2021 (see figure 2). At present, almost 90% of gas production is flared or re-injected because of the lack of commercial outlets. World Bank data shows 1.4bn m3 of gas flared in 2022 (see figure 3).

In 2016, the government endorsed the World Bank’s Zero Routine Flaring by 2030 initiative, including a pledge to cut greenhouse emissions by half between 2016 and 2025, although the target is not binding. Libreville hopes that building domestic gas demand will help curb the practice.

Regional context

Perenco appears to be building on the success of its Cameroonian FLNG project, which it has operated offshore the Port of Kribi alongside Cameroon’s national oil company Société Nationale des Hydrocarbures (SNH) since May 2018. The Hilli Episeyo FLNG vessel has a production capacity of 2.4mn mt/yr, but actual production has fallen short of this figure. It was the world’s second FLNG vessel and the first to be converted from an LNG carrier.

The Hilli Episeyo has been 100% owned by Golar LNG since March, when the company bought New Fortress Energy’s (NFE) 50% stake in the project in exchange for $100mn, Golar taking on the project’s remaining $323mn debt obligations and Golar’s previous holding of 4.1mn shares in NFE.

Here too, Perenco has coupled domestic energy supply with LNG production, supplying LPG and condensate to the Cameroonian market.

Perenco’s output currently breaks down as 75% oil and 25% gas by barrels of oil equivalent. However, through its long experience on the Gulf of Guinea, it does appear to have identified a gap in the market for LNG. It has operated in Gabon for 30 years, with Gabon and Cameroon being its two biggest sources of production, yielding 110,000 boe/d and 100,000 boe/d in 2022.

Perenco’s output currently breaks down as 75% oil and 25% gas by barrels of oil equivalent. However, through its long experience on the Gulf of Guinea, it does appear to have identified a gap in the market for LNG. It has operated in Gabon for 30 years, with Gabon and Cameroon being its two biggest sources of production, yielding 110,000 boe/d and 100,000 boe/d in 2022.

Nigeria, Angola and Equatorial Guinea already operate larger LNG plants on the Gulf of Guinea, but Perenco’s plans are opening up the commercial development of smaller stranded gas reserves in the region. Apart from Gabon and Cameroon, a new LNG project is possible in Congo-Brazzaville, following the conclusion of a preliminary agreement between Italy’s Eni and the government of Congo-Brazzaville.

It will be interesting to see whether Perenco becomes involved in this venture in some way or sets out to develop its own small LNG project in the country. It is already active in Congo-Brazzaville where it operates the Emeraude, Likouala and Yombo fields with an FPSO and, in December, it announced a discovery on its offshore Pointe Noire Grand Fond (PNGF) Sud licence with “good oil and gas shows”.

Perenco’s investments suggest that more of Africa’s smaller stranded gas reserves could be tapped for LNG in the future. Maturing LNG technology is convincing developers that small projects are commercially viable and is also persuading governments that it is worth engaging with potential investors to see how the investment regime can be adapted to enable them. Cameroon and Gabon may only be the beginning.