Pipeline Gas Versus LNG - Increasing Competition in Europe and Asia

Pipelines from the US to Canada and Mexico, Bolivia to neighbouring countries in South America, and North Africa to Europe provide significant examples of the more traditional regional trade patterns, but of course the extensive pipeline exports from Russia to Europe are the most well-known, and increasingly controversial, example.

By contrast, the Asian gas market has been dominated by LNG. This is mainly because the largest traditional markets have been relatively remote—Japan and Taiwan are islands, and South Korea is a peninsula cut off from access to piped gas.

|

Advertisement: The National Gas Company of Trinidad and Tobago Limited (NGC) NGC’s HSSE strategy is reflective and supportive of the organisational vision to become a leader in the global energy business. |

Furthermore, efforts to connect Asian countries via a pipeline network have largely failed due to a deficiency of indigenous gas reserves in the region and the lack of a coordinating body (such as the EU in Europe). The most significant recent attempt has been the Trans-ASEAN Gas Pipeline, but hopes of a multinational pipeline system in the East are now fading. As a result, LNG, sourced both from relatively proximate exporters such as Indonesia and from more remote locations in Australia and the Middle East (predominantly Qatar), has dominated.

One factor that pipeline and LNG exports have historically had in common is that they have been based on expensive multiyear developments that could only be justified, by both the companies involved and the banks providing the finance, on the basis of long-term contracts, which were generally based on a price linked to oil. This placed the volume risk with the buyer (who would guarantee to purchase gas over, for example, a 20-year period) and the price risk with the seller (who would offer gas at a discount to a key competing fuel, namely oil).

However, this traditional model has now started to break down, catalysed by the introduction of the Third Energy Package in the EU, which has liberalized the market and stimulated competition between all forms of gas supply, and the arrival of US LNG, which is priced relative to the Henry Hub spot price. The EU has also encouraged its member countries to increase the diversification of their supply options, which has led to the construction of numerous receiving facilities where LNG can be regasified and dispatched into the pipeline network.

Of course, the fact that LNG is largely regasified before use and sent to consumers in a gas pipeline underlines the fact that it is exactly the same product as gas imported via pipe, so the competition between the two is in reality competition between alternative sources of natural gas. The key difference, though, comes in the flexibility of the product being offered, as pipelines by their nature connect one seller with one buyer, while LNG offers the opportunity for redirection to any customer prepared to pay the highest price. This has not always been the case, as LNG contracts have often included destination clauses that have restricted on-sale, but the introduction of US LNG exports that have largely been sold FOB in the Gulf of Mexico (and therefore with no destination restrictions) has dramatically changed the market. Both sellers and buyers have now become accustomed to trading LNG in order to optimize their risks and returns; and with Europe offering a liquid and competitive market where gas can always be sold at the prevailing market price, the foundation for a truly competitive global gas market has been laid.

Competition in Europe between Russian gas and LNG

That this competition is manifesting itself in Europe is not really a surprise, as it is arguably the most diversified gas market in the world. Indigenous gas supply, although declining, still plays an important role; pipeline imports arrive from North Africa,

Norway, Russia and soon from Azerbaijan, while the continent’s 220 billion cubic metres (bcm) of LNG regasification capacity gives it access to a host of other suppliers.

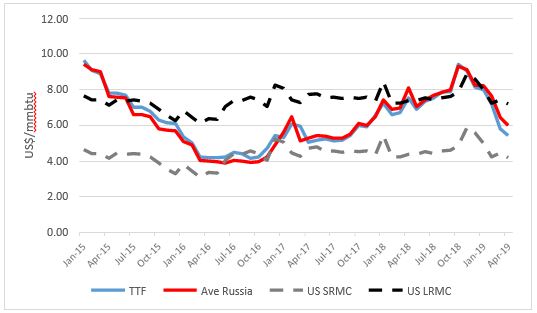

In reality, though, the competition boils down to Russian pipeline gas versus LNG, as the other sources of pipeline imports are effectively at capacity, with the rivalry heightened because at the margin it would appear that the competition is between Gazprom and new US LNG exports. US LNG, based on the Henry Hub price plus other costs of supply, has become a proxy for the marginal cost of LNG, either on a long-term basis including all fixed costs (liquefaction in particular) or on a short-term cash basis, and it would appear that the Russian gas price to Europe, which now tracks the spot market very closely, fluctuates between these two levels according to whether the market as a whole is under- or over-supplied.

Comparison of gas prices in Europe with US LNG export costs

It would certainly appear logical for Gazprom, with its fixed pipeline export infrastructure, to want to maintain a gas price between the short- and long-run marginal costs of a major competitor. On the one hand, the goal is to maximize revenues and profits by avoiding too low a price (there is no need for the price to fall below the short-run marginal cost of US LNG, as it will then logically be shut in) while on the other hand, it would not make sense to push the price above the long-run marginal cost for an extended period, as this would create greater competition in the long run by encouraging new LNG projects to be developed.

That said, there are inherent constraints in the competition between pipeline gas and LNG in Europe. From a Russian perspective, the obvious constraint is pipeline capacity. In the winter of 2017/18, when there was a significant cold snap, it became apparent that the Russian export system was already full on some days, with any flexibility being provided by the transit system through Ukraine, as Nord Stream and the Yamal–Europe system were consistently full. This raises the issue of politics, of course, and the potential constraints that could be placed on the Russian export system if Ukraine transit ends in January 2020, and/or the EU blocks the new Nord Stream 2 pipeline, and/or the EU finds a way to constrain flows to Europe through the Turk Stream pipeline across the Black Sea. This highlights the important, if obvious, issue that pipelines are strategic geopolitical assets and that the ability of gas supplied through them to compete with alternative sources of supply will always be driven by more than commercial factors.

LNG, on the other hand, offers a different perspective because at the margin, once it is on the water, it can be diverted to whichever market is the most profitable. This is particularly relevant in a tight market, when prices are rising because supply is short, with Asia being viewed as the most likely premium market because of its dependence on LNG. Conversely, in a loose market with plentiful supply, LNG can be diverted to whichever market is available and has space for it—at a price. This tends to be Europe, because of its liquid market and its current excess of receiving capacity (which even in 2018 was only used at an average rate of around 30 per cent). As a result, the competition between LNG and Russian pipeline gas in Europe tends to be most obvious in times of oversupply (such as the first half of 2019), when the flexibility of LNG flows clashes with the flexibility inherent in Russian export contracts at the market price in Europe.

Are we about to see the same dynamics in Asia?

An obvious question, given the growth of gas markets in Asia, is whether pipeline gas can provide an interesting competitive alternative in the East as well as in the West. Despite the apparent failure of the Trans-ASEAN Gas Pipeline, it would appear that the answer, at least in some countries, is yes, with China providing the most obvious example of a country that is maximizing its diversification options.

Having become a gas importer in 2009, China has developed a multilayered approach to gas supply. As with the EU, indigenous production plays an important role, and in this case a growing one, albeit with some uncertainty about the pace of future growth from the country’s shale resources. Nevertheless, the pace of demand growth (which averaged more than

15 per cent a year in 2017 and 2018) means that the import requirement has been growing, and a ‘compass’ of import options has been developed. From the West, pipeline infrastructure has been constructed to bring gas from Central Asia, with Turkmen gas as the foundation, supplemented by exports from Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan set to bring up to 65 bcm by the mid-2020s. From the South, a pipeline has been constructed from Myanmar with a capacity of 12 bcm, although only 4 bcm is currently being exported. Both of these sources of gas have seen major Chinese investment in the supply countries, meaning that Beijing has developed significant influence over its imported gas.

In the East, a growing number of regasification terminals have been built to allow diversification into LNG imports from multiple sources. Initial contracts were signed with Australia, but China has now become the fastest-growing market for LNG in the world, meaning that all new projects are keen to offer their output to one of the many Chinese buyers. Mozambique LNG, for example, would have been unlikely to take its final investment decision in June 2019 without at least one contract in place for sales to China. Regasification capacity at the end of 2018 totalled 73 million tonnes (mt), with this set to rise to 78 mt by the end of 2019 and to as much as 100 mt (about 135 bcm) by the end of 2020. With demand set to reach around 340 bcm by then, this means that LNG could supply more than one-third of total Chinese gas demand.

However, this supply does not come without risks, and these are not dissimilar to the risks associated with pipeline gas in Europe. In China, though, they concern the actions of the US rather than Russia. On a geostrategic level, the Chinese authorities are concerned that, although their LNG imports come from multiple sources, their routes to market are potentially a risk because they could be closed off by the navy of a competing power—the most obvious risk being the US Pacific Fleet. All LNG from the West would tend to pass though the Malacca Straits, a choke point that could be blocked, while other supply would pass through the South China Sea and could also be obstructed by the US Navy. Given the current antagonism between Washington and Beijing, which has escalated into a trade war that includes tariffs on US LNG imports to China, the security-of- supply implications for the Chinese economy are significant.

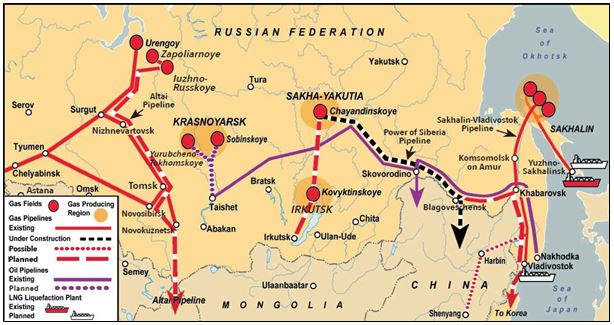

As a result, the northern axis of the Chinese gas import compass has become much more important. Pipeline gas from eastern Siberia provides a potentially vital source of supply (up to 38 bcm per annum by 2025) that could clearly displace LNG that might otherwise have been delivered to China. Although it comes with the same strategic risk that all pipelines bring, namely a long-term exposure to a foreign power for a vital energy source, it would seem that the Chinese authorities feel relatively confident in their bargaining power over Russia in this instance, given that the gas would otherwise be stranded. Indeed, negotiations for a further two pipelines, one in the Far East from Sakhalin and one in the West via the Altai region of Russia, are underway but are effectively at the behest of the Chinese authorities. Nevertheless, the option to authorize these two new routes provides further negotiating power both with Russia and with LNG suppliers, as the threat of reducing future LNG demand by contracting for another long-term pipeline deal from Russia can keep negotiations over new LNG contracts honest.

Indeed, the Chinese authorities have gone even further in ‘playing off’ LNG and pipeline supplies by taking an interest in Russia’s expanding Arctic LNG projects, run by Novatek on the Yamal and Gydan peninsulas. Chinese companies have taken equity in both, and a 3 mt per annum contract has been signed with Yamal LNG, as China seeks to have an interest not only in LNG supply but also in the development of the Northern Sea Route, which can provide an important strategic artery to Europe. In addition, a Chinese company (Beijing Gas) has been in negotiation with Rosneft over possible gas exports, demonstrating China’s ability to create competition between the three main players in Russia’s gas industry.

Russian gas pipelines to China

Of course, these options are not available to all Asian countries, as their gas markets are not as large and their geographical location does not offer such opportune diversification options. Nevertheless, for some the example of China can provide a good pointer to future supply planning. India, for instance, already imports LNG and is looking to explore opportunities for pipelines from the Middle East and Central Asia, while Bangladesh and Pakistan may also be able to promote both forms of imports.

At the end of the day, of course, LNG and pipeline gas are homogeneous products, but the different elements that they bring to an import portfolio, in both commercial and political terms, can offer important strategic as well as economic diversification.

The statements, opinions and data contained in the content published in Global Gas Perspectives are solely those of the individual authors and contributors and not of the publisher and the editor(s) of Natural Gas World.